On Point

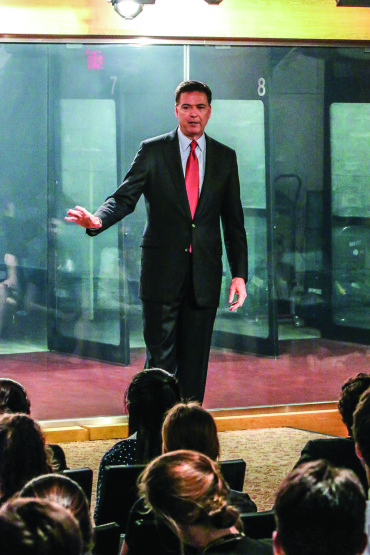

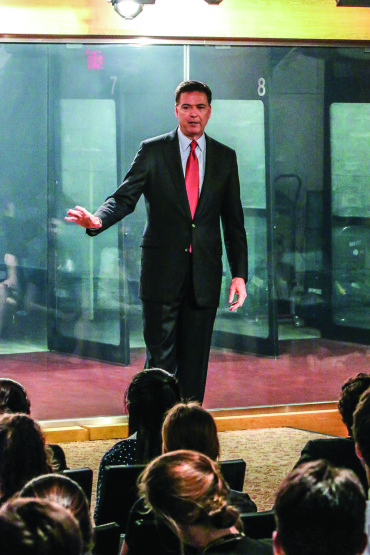

James Comey '82, LL.D. '08 lights a fire for W&M students in D.C.

July 1, 2015

By

Ben Kennedy '05

WASHINGTON – When the FBI agent fires it on full automatic, the 56 assembled William & Mary students nearly jump out of their seats, although they’re safe behind bulletproof glass. A few moments later, another agent presses a button to instantly turn the glass opaque, just in time for the FBI director to walk in. It is an unusual classroom.

Deep within the J. Edgar Hoover Building’s windowless hallways and security perimeters, James Comey ’82, LL.D. ’08 says “Hark upon the gale,” and the three classes of the William & Mary Washington Office’s D.C. Summer Institutes (DCSI) can calm down. They know they’re in friendly company.

“This is something I’ve looked forward to all day,” says Comey, now in his second year as FBI director. He — and the DCSI faculty and staff — are engaged with helping these 56 undergraduates find success crossing the seemingly vast gap between student life and the world beyond. To that end, DCSI is a remarkable process, but Comey is a remarkable FBI director.

In January, Jim Comey stood at the funeral of a New York police officer, Wenjian Liu, who was murdered in retaliation for the 2014 deaths of Eric Garner in Staten Island, N.Y., and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. Comey decided then, amidst the pain of the victim’s family and the confusion of Liu’s fellow NYPD officers, that he was in a unique position to say something.

The next month, Comey took the stage at Georgetown University to speak about “hard truths” and the relationship between law enforcement and the diverse communities it protects.

“We can roll up our car windows, turn up the radio and drive around these problems,” he said, “or we can choose to have an open and honest discussion about what our relationship is today — what it should be, what it could be, and what it needs to be — if we took more time to better understand one another.”

The speech, considered the first of its kind by an FBI director, was a measured look at some of the issues that underpinned violent protests in Ferguson, New York, and elsewhere. The New York Times called it “unusually candid” in its attempt to combat widespread “unconscious bias” and promote the “selfless service” of police officers at the same time.

“Those of us in law enforcement must redouble our efforts to resist bias and prejudice,” he said. “We must better understand the people we serve and protect—by trying to know, deep in our gut, what it feels like to be a law-abiding young black man walking on the street and encountering law enforcement. We must understand how that young man may see us. We must resist the lazy shortcuts of cynicism and approach him with respect and decency.”

But the seeing must go both ways. Citizens of all races, Comey said, need to understand the challenges facing law enforcement as well.

“They need to see the risks and dangers law enforcement officers encounter on a typical late-night shift,” he said. “They need to understand the difficult and frightening work they do to keep us safe. They need to give them the space and respect to do their work, well and properly.”

Then, in mid-April, Comey was invited to speak at the National Tribute Dinner for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. His remarks, reprinted the next day in the Washington Post, called the Holocaust “the most horrific display in world history of our humanity, of our capacity for evil and for moral surrender.” He also said that he requires all new FBI agents and analysts to visit the museum in order to gain a grim understanding of human nature’s horrific extremes.

“Good people helped murder millions,” Comey said. “And that’s the most frightening lesson of all — that our very humanity made us capable of, even susceptible to, surrendering our individual moral authority to the group, where it can be hijacked by evil.”

INTEGRITY: Comey cites his William & Mary liberal arts education as a major factor in his decision to commit to public service.

They are the measured, thoughtful words of a man who has spent much of his career in the legal and law enforcement fields, but comes from a William & Mary religious studies background.

“A feature of both speeches,” he says later in an interview, “was something that I think is a feature of human existence: the danger of falling in love with our own perspective.”

Comey has served as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York — a critical precinct that includes Wall Street and Manhattan — and has held high-level positions in finance and at Lockheed Martin. During the George W. Bush administration, he was deputy attorney general, and was named FBI director by President Obama in June 2013. It all adds up to a wide variety of viewpoints.

“Because you can only see the world through your own eyes, there’s a great danger. You will think that that is the best view of the world, you will neglect that other people see the world differently than you do, and your perspective could be wrong.”

He tells the gathered William & Mary students to cultivate these important traits for their job searches.

“When I hire, I care about the following things in the following order: values, abilities, skills,” he says. “Most people hire in the wrong direction.” Integrity, honesty, humility and empathy are the most critical traits.

“Staring at human nature is something I started learning about before I went to William & Mary and cultivated at William & Mary,” he says. “It’s been a feature of my whole life. I’m not perfect at it — I’m trapped in my own perspective. But I have worked so hard to try and force myself to understand the world as others might see it. I think that makes me a better leader.”

Leadership, as it turns out, is the theme of the summer for some of these students. A day later and a mile and a half away, just a few blocks from the whirling Dupont Circle, the DCSI students are having lunch. Among them is Drew Stelljes Ph.D. ’07, who is spending his fifth summer teaching a class on leadership and community engagement.

“The course is aimed to help students understand leadership theory,” he says. “And then, through site visits — with humility — we critique and observe individuals and organizations on the extent that they apply the leadership theories that we’ve learned.”

“Much of what Director Comey speaks of really resonates with what I’m trying to do,” Stelljes says. “I’m trying to support our students to develop a sense of purpose and to understand more clearly where their strength areas can fit into organizations whose mission and vision they believe in.”

FIELD TRIP: On May 19, all three classes of the 2015 D.C. Summer Institutes visit the J. Edgar Hoover Building in downtown Washington for the visit with Comey.

That sort of personal envisioning is a critical part of DCSI’s purpose each summer. Adam Anthony ’87 is the director of the William & Mary Washington Office and has seen class after class of W&M students come through the nation’s capital for a transformative experience.

Each student is here this summer through one of DCSI’s classes: some in Ron Rapoport’s American politics institute, others in Jeremy Stoddard’s new media institute, and still others learning from Stelljes. Comey’s question-and-answer session is a tough act to follow, but the visit to the FBI is truly just the beginning.

“Being in Washington helps [students] picture themselves in a particular setting,” Anthony says. “They love to go on site visits. They can see themselves walking down the halls of somewhere maybe they’d like to work.”

“Something that I think was spot-on with the institute in general was — and that our professor Drew has been working with us a lot on — is how you want to see yourself and how you can see yourself leadership-wise in the leaders that we visit,” says Phoebe Galt ’17. “For [Comey], it seemed like he had everything together in all respects. I appreciate the experience and seeing both sides of him a little bit.”

Roxane Adler Hickey M.Ed. ’02 is assistant director at William & Mary’s Washington Office, and she is convinced that these visits — to the FBI and others like it — are keystone experiences for DCSI’s students.

“We believe that our programs give students an opportunity to come here and figure out who they are and who they’re going to be,” she says. “Whether that’s your internship, or listening to someone like Jim Comey, or learning how to get to the grocery store, you see what you want, and you see what you don’t. You get to make some decisions on where you want to go from here and what kind of person you’re going to be in your career.”

To do that, the Washington office staff works hard to help great minds meet: professors, students, mentors and alumni alike. First, the students learn from alumni all over Washington during site visits like the May trip to the FBI. For two weeks, these visits, along with seminar classes taught by professors in residence, dovetail into an intensive experience that Adler Hickey says is just as rigorous as any class in Williamsburg. Then, the students spend the remaining 10 weeks in a related internship, often facilitated by alumni connected with the D.C. office. Right now, William & Mary’s DCSI students are interns in a variety of Washington-area organizations, including the National Endowment for the Arts, Nike and the White House.

“There are about 60 schools that operate in Washington, and none of them really do it like we do,” says Adam Anthony. “And I think that’s about the way William & Mary likes it.”

Anthony has been director of the D.C. office since 2004, and has met with a dozen of these other universities looking to set up operations in Washington.

“When they get to us, they say, ‘Oh, OK, so this is how you can do it,” says Adler Hickey. “And then they have five trillion questions.”

“[Students] get to experience D.C. and they get to do it in a way you can’t learn in a book or a conversation,” she says. “So pairing that with an internship where they get to try one of those things on their own means that they can leave here with a really solid sense of what they want to do next, and a huge network.”

Those networks make all the difference as students transition from undergraduates into job-seeking young alumni. Today’s guest speaker at a DCSI site visit is tomorrow’s internship connection, says Anthony. And from there, students can build relationships on their own.

“These speakers are inspiring and informative,” says Adler Hickey, “but they’re the beginning of our network. Our students get jobs, get internships and have life-changing discussions with people when they’re done here.”

A seminar class at W&M’s Dupont Circle offices.

During the Comey visit, the FBI director fields lots of questions on a variety of topics, but it’s easy to get the impression that many of the students want to come and work for him.

“I can see [the Q&A] having a big influence and maybe pushing students toward public service,” says Anthony, who has seen students join fields in government, non-profit and private sectors alike.

“With 16,000 alumni in D.C.,” says Adler Hickey, “there’s someone doing something that you’re interested in. There’s someone who can help connect you so you’re not just a résumé in a stack.”

To that end, the Comey visit was a great kickoff to DCSI. “It was really valuable because he spoke about the merits of his professional career and the values that he believed in,” says Michael Sildivi ’17. “We could ask things about the nature of his work, but it was also a motivational speech in a lot of ways.”

So just as Comey seeks to bring differing cultures and people together to increase understanding, DCSI requires a similar level of integration.

“This kind of program,” says Anthony, “to really function very well, requires administrators, faculty and alumni holding hands, progressing together.”

Progress, Jim Comey says, comes from culture. The FBI, he’s learned, has a “mission culture.”

“It’s like a gravitational force that’s instilled in you. Frankly, even if I tried, I couldn’t screw it up too much.”

This, he repeats, is the primary motivator in getting things done. You can’t talk your way into a productive, encouraging culture. You have to lead by example.

“What a leader says is important, but actually more important is what do they do,” Comey says. “How do they walk? Where do they go? What does their face look like? How do they hold their shoulders? I spend a lot of time trying to model things that are important to me.”

For a man who has served in high-level positions in both Republican and Democratic administrations, a relentless focus on leadership and the proper perspective has helped him navigate today’s fractured political landscape.

“When I deal with people of all stripes — especially politicians — it helps me to understand that people are great at convincing themselves of the righteousness of their own positions,” says Comey. “Knowing that and taking that into account when you’re dealing with people is critical to being successful at any walk of life. I don’t mean to focus just on politics.”

He explains how changing culture and humility have helped bring the two largest American intelligence organizations closer together despite years of bitter rivalry. The post-9/11 intel community would be unrecognizable to the old guard, he says: today the No. 2 person in the FBI’s national security branch is a CIA officer. The two organizations are now connected person-to-person on every level, like a zipper.

“Remember, culture is the way things are really done no matter what they tell you,” he explains to the students. “You can’t tell your way to integration between the FBI and the CIA: you have to sit them

together and then they’ll all start to think of themselves on the same team.”

HANDS ON: During the summer, students visit a number of sites around Washington, including a trip to DC Central Kitchen.

It relates back to his touchstones of empathy and perspective and Comey’s two speeches from earlier in the year. He wants these students (and future members of the Tribe) to focus less on learning software programs and more on learning thoughtful methods of reasoning and understanding. He did this, as a chemistry major who added a religion major after a fateful Hans Tiefel course: “Death.”

“I spent a lot of time thinking about ethics and studying different faiths,” he says. “Taking philosophy and stretching myself, I was learning to see the world through the eyes of others, which is what makes a great liberal arts education.” Comey hopes William & Mary never loses sight of those qualities.

“No matter how the world changes,” he says during the interview, “if you are a reflective, low-ego, thoughtful, effective communicator who connects well with other people, you will be successful. They can throw anything at you, but if you have that, you will do well.”

The FBI will have to continually change during Comey’s 10-year term. By 2023, even more of the threats facing America will come via the Internet, and the Bureau will need more people with the right expertise to fight them. If they can meet the coming challenges, William & Mary students can be part of that vanguard.

“If you spend time trying to understand the world, understand the world’s problems and the challenges that are inherent to being a human being, it will light a fire in you to want to be a part of making that human existence better,” he says. “It will continue to feed the legacy of service that the College has felt since its founding.”