Shooting Script

A New York Lawyer's Journey Through Movies,

July 1, 2014

By

Kelley Freund

FADE IN:

EXT. CABIN IN THE WOODS — DUSK

The cabin is in the mountains of northern Georgia, near the town of Cleveland. Out in the middle of the woods, miles from anywhere, there’s no one around to hear you scream.

In 1995, attorney and film producer Samuel Rael J.D. ’73 used this cabin to shoot scenes for an independent feature film he was producing called “Deadly Run.” Thirteen years after the movie was released, the story took an interesting turn.

An elevator operator takes a man and woman to the fourth floor of a building. As the elevator heads up, the man sighs quietly. He wants better for his son. He wants his son to go to college.

No one in Rael’s family had gone to college, but fate was decided early on. “We didn’t have any money, so they really wanted me to be a lawyer,” he said. “I see in my scrapbooks at the age of 5, they have me studying to be one.”

After attending New York University, Rael applied to the Law School at W&M, “I got into a lot of fine schools, but I thought William & Mary would be small and have a lot of good-looking girls,” said Rael.

While at the College, Rael represented The Flat Hat in 1971, after the newspaper had written some obscenities in a February edition and received backlash from the administration. Rael wanted to fight for the paper’s free speech. “I was a rabble-rouser,” Rael said. “I think I still am.”

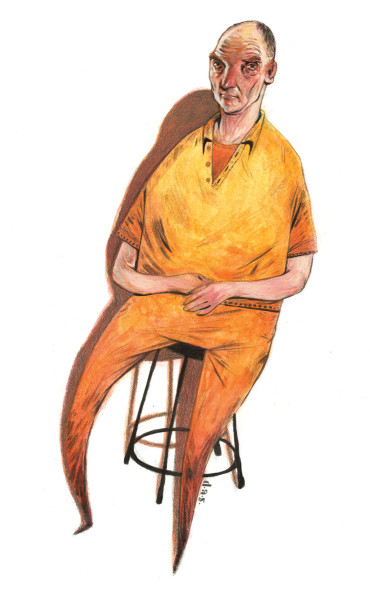

Illustration by Danny Schwartz

After graduation, Rael came to Atlanta and opened his own practice. “The whole purpose of having your own practice is to be on your own and do your own thing,” Rael said. “That was three-quarters of the reason to be a lawyer. Very little of it had to do with money, as I can now attest.”

But he wanted to pursue other interests as well. Acting was what Rael actually loved to do and he was a firm believer you should do what you love — “as long as you can keep the creditors away” Rael said. “Incidentally, I am a terrible actor. I even had a girlfriend who ran a theatrical agency and she wouldn’t put me up for auditions.”

He decided that since he was so horrible at acting, he could use his background in law to produce independent films. Working on movies allowed Rael to put his artistic flair to use, while still earning a steady paycheck as an attorney. “I could accomplish what I really wanted; it’s a little of both. Producing seemed natural.”

The woods near the cabin. A woman stands with her back against a tree. She is scared, shaking. Cautiously she peeks around the trunk. She sees no one. Not the man lurking behind another tree 50 yards away.

“Deadly Run” was Rael’s first film. While he was gravitating towards something with beach bimbos, a man named Gary Hilton had other ideas.

Rael first met Hilton in the 1980s when Hilton was caught trespassing on Atlanta city property and Rael was appointed as his attorney. Rael went on to defend Hilton on several charges over the years, including arson and false solicitation of charitable donations. The two began to socialize more outside of the courtroom, and when Rael mentioned he wanted to produce a movie, Hilton jumped right in with the story idea.

“Deadly Run” tells the story of a respected Atlanta-area realtor who is leading a double life. He has a wife, son and daughter, but he also has a cabin on a rural piece of land, where he takes abducted women, setting them loose in the woods and hunting them down. Hilton served as a consultant on the film, even finding the location of the cabin in Cleveland, Ga.

The movie went straight to video and eventually Rael and Hilton went their separate ways. But it wasn’t the last time Rael would hear about Hilton.

A Chevron gas station in DeKalb County, Ga. Hilton is vacuuming his van and washing out the interior. Inside the van, the rear seatbelt is cut out. Police pull up and surround Hilton. In a nearby dumpster, they find the seatbelt and fleece tops with blood on them.

Meredith Emerson, a 24-year-old University of Georgia graduate, was last seen alive hiking with her dog Ella on Blood Mountain in northern Georgia on New Year’s Day in 2008. She was seen with an older man on a spur trail connecting the Appalachian Trail with a parking lot. On Jan. 4, a witness at the gas station called DeKalb County police and said the man they were looking for was out in the parking lot, cleaning his vehicle.

Hilton confessed to murdering Emerson when the prosecution agreed to take the death penalty off the table if he led investigators to her body. Thirty miles away from the cabin Rael had used for “Deadly Run,” the cabin Hilton himself had suggested, Meredith Emerson’s decapitated body was found. Hilton said he asked Emerson for her debit card PIN and when she didn’t give him the correct one, he kept her four days before killing her and decapitating her. He told investigators that he could not bring himself to kill her dog, who wandered into a grocery store 60 miles away.

“I was flabbergasted,” Rael said. “I had no clue whatsoever. Which is what is very strange about it. I’d like to think I’m a good judge of people and know how to analyze somebody. Yes, he had some crookedness in him and a couple of screws loose. But then again, so do many of my friends.”

Rael has pictures of himself and Hilton together, hanging out with friends, even Rael’s family. “He was very nice to me and to everyone I knew, wonderful to animals, had that kind of desire to just help you. I had absolutely no fear of him whatsoever. I had been much more fearful of the last two women I went out with than I was with him.”

Hilton was also charged with the murder of Cheryl Hodges Dunlap, a nurse from Florida, who was found decapitated in 2007 in the Apalachicola Forest in Florida, her headless and handless body found by a hunter. When Hilton was arrested in north Georgia for the murder of Emerson, blood on a sleeping bag and pants found in his van were matched to Dunlap. A jury voted unanimously to recommend the death penalty. He also eventually confessed to the murder of John and Irene Bryant, an elderly couple from North Carolina who vanished while hiking in 2007.

“All I wanted to do for my movie was have a little blood, a little excitement, and I have a serial killer help me make my serial killer movie?” Rael said. “What is going on? That in itself is a movie. As a matter of fact, it should be my next one. Would I have ever even dreamt that the very first movie I did, we’d be talking about it 20 years later? Life is stranger than fiction.”

Rael has definitely had his fair share of interesting experiences as a film producer.

“In ‘Deadly Run,’ we had a scene where there were a lot of folks with machine guns and weapons in a nice neighborhood.

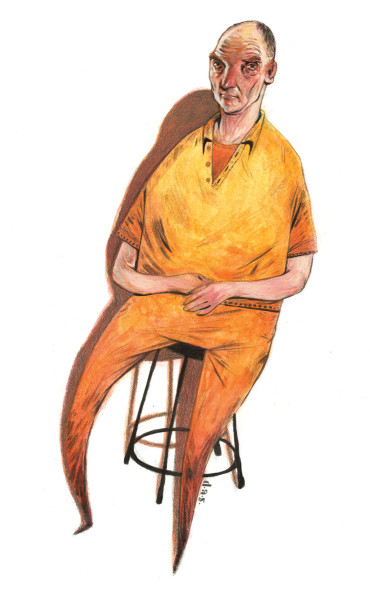

Illustration by Danny Schwartz

But apparently somebody forgot to tell the police and they got 911 calls. Eight or nine SWAT cars all ran in. But it was OK because we filmed it. It’s a scene that we couldn’t have otherwise done.”

Once the guy in charge of props bit the ear of the line producer in a dispute. Another time, the sound guy felt like he wasn’t going to get his last week’s pay, so he held the sound tapes and was eventually arrested for extortion.

“If you could think of every disaster … the Hindenberg would be nothing compared to making a feature-length film. The making of a low-budget films is an entire universe away from what you think when you go watch ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ or ‘Spiderman,’” Rael said. “Instead of Sylvester Stallone, you get Sylvester Stallone’s brother. Instead of Glenn Close ’74, D.A. ’89, you get Glenn Close’s hairdresser.”

But Rael wouldn’t have it any other way. “It’s an exciting adventure. You nurture it, you use your creative energies. Independent films give you a lot of freedom to express yourself. There are no committees and no boss to tell you, ‘Don’t do this.’ The best part (besides the girls) is being able to create something from nothing.”

A courtroom in southern Georgia. Rael is standing before a jury, wielding a baseball bat. His client is accused of attacking someone with the bat.

Rael cracks some joke about Ted Williams and the jury laughs.

While practicing law and film producing might seem worlds away, Rael says they are actually pretty similar. “When you’re before a jury it’s just like a movie. You have to be able to relate a story and make things interesting and exciting.”

And Rael certainly does a good job with that. “I think you have to break the ice before a jury,” he said. “They find it amusing. I’ve had judges laughing uncontrollably, but I wasn’t trying to be funny. Courtrooms are very solemn and quiet and all of sudden I’ll hear the judge let out a howl and I know I’ve done something.”

Rael has worked his share of interesting cases. He once had a Mafia trial in the Southern District of New York, where he represented an exotic car dealer. The dealer’s wife was the daughter of one of the members of the Five Families. They had gotten the man involved to change titles and then they would sell cars overseas.

“I’ve always got a half dozen murder cases going on appeal or in court, so I’m busy. But in order to retire, I probably shouldn’t be making movies. Actually I shouldn’t be in criminal law at all. I should’ve listened to my professors and done a couple of trusts and wills and estates and be done with it. They warned me.”

But in a way, Rael is suited to be a trial lawyer. As someone who boxes in his spare time, Rael’s time in the ring has helped him be a fighter in the courtroom: “People want you when they’re facing some serious cases, they want you to fight for them hard and that’s exactly what boxing does. It prepares you to be able to be in a courtroom as a fighter. You have to be a fighter; it’s the nature of the game.”

Rael tries many of his cases out in the country, in a lot of small towns and very southern parts of Georgia. “It’s funny. I came from New York and I would have to explain in Atlanta that I’ve come from New York, but it’s OK. And then when I go to the small towns, I have to explain how I’ve come from Atlanta, but it’s OK.”

CUT TO:

INT. OFFICE — DAY

Rael’s business card: Samuel Rael, criminal defense attorney “Fighting for justice.”

FADE OUT.

END.