Liftoff

A New Universe of Information Overload and Changing Disciplines is Coming ? And William & Mary Has a Plan

January 1, 2016

By

Ben Kennedy '05

Last semester, William & Mary launched the long-anticipated College Curriculum, or COLL, beginning with the freshman Class of 2019. Students face a rapidly changing world, often with too much information and too little perspective. But COLL is prepared for it. It’s the framework for a bold new strategy aimed at revolutionizing general education. By forging new connections between the breadth and depth of the liberal arts, William & Mary is charting a pioneering course all its own.

WELCOME TO THE OVERWHELM

When the previous curriculum was implemented in 1993, Bill Clinton had just become president. Jurassic Park dominated the movie theaters. The modern European Union was just taking shape. A certain historic university celebrated its 300th birthday. Fourteen million people used the Internet to the tune of 100 terabytes of data over the course of the year.

By 2008, when that General Education Requirement program (GER) was in its 15th year, 3 billion people were using the Internet. Global traffic amounted to 100 terabytes per second. The economy was poised to take a nosedive and Washington, D.C., languished in political gridlock. The world had become inarguably different.

Also during that year, William & Mary undertook an early university-wide strategic planning effort. The view of the faculty was clear: the College needed to reaffirm its commitment to the liberal arts. And as a matter of course, universities tend to review their general-education curricula every two decades or so.

“The curriculum review and later reform was all part of that,” says Professor Gene Tracy. “It was to have a conversation about what it is that we need to do to be a liberal arts institution, and making sure that our curriculum reflects those values.

“What does it mean to be a liberal arts institution in the early 21st century? How are you going to stay relevant to the current generation?”

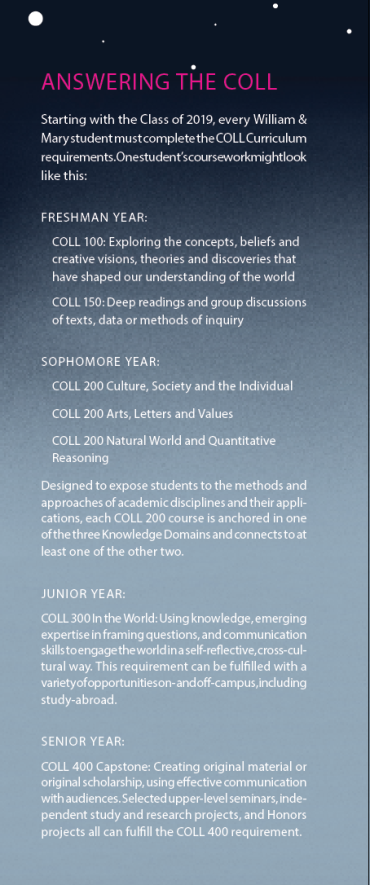

Tracy is Chancellor Professor of Physics at William & Mary, and director of the Center for the Liberal Arts (CLA), the engine helping to bring COLL to life, seven years after those first meetings. Unlike the GER system, where credits earned in high school could count toward some of the required classes, COLL will require every William & Mary student to fully experience the brave new world of liberal arts at the College (AP & IB credits still count toward electives and a student’s major; see sidebar). The days of “Math of Powered Flight” or “Great Ideas in Physics” — survey courses for non-majors — are changing. Every COLL course is designed to be relevant to each student, either through content or methodology.

The COLL curriculum for freshmen now centers on great ideas and big questions, and uses fundamental facts and source materials in service of approaching and answering those questions.

“It’s less about giving you that information than teaching you to know what to do with it,” says CLA fellow Professor Nick Popper, the Class of 1952 Professor of History. Pure facts, Popper says, are no longer at a premium.

“Even in the short time I’ve been teaching, I’ve noticed there have been proliferating ways in which students have access to information,” says Popper. “Back when I was an undergraduate, you often had to go to the library in order to find out fairly basic, essential facts that are now housed in every student’s pocket.”

Despite this new abundance of facts, he sees a “helplessness” in students as they navigate instant access to more information than anyone in history.

“That just applies to everyone in this society who has a basic Internet connection,” he says. “But it doesn’t differentiate. It’s not a higher form of learning, because it’s something that’s broadly shared. That is fundamentally a good thing. The problem is, at the same time, that saturation has made it harder to process for many people.”

“I remember reading somewhere that Goethe said that the invention of the newspaper destroyed theater,” Gene Tracy says. “His argument was: how could you expect someone to engage with a difficult piece of drama if their head is abuzz with rumors of war three countries over, from the newspaper they read at dinner? If that was perceived to be a problem back then, well…”

Tracy smiles and shrugs, but he sees the mission clearly: “If we do this right, the coming generations will be better-informed and more nimble in their outlook, than ever before,” he says. “And if we do it wrong, they’ll just be overwhelmed. They’ll collapse and hunker down into a mental fallout shelter, [saying] ‘Protect me from the world — I’m terrified of it, it’s changing so fast.’”

A 20-year-old curriculum was not going to cut it by William & Mary’s standards. If the undergraduate course catalog is truly to “liberate and broaden the mind, to produce men and women with vision and perspective as well as specific practical skills and knowledge,” then changing was a responsibility.

“I believe the liberal arts is, in fact, going to be necessary to navigate the coming world,” says Tracy. “It’s going to be changing even more rapidly — any given type of technology is going to become obsolete even faster than 20 or 30 years ago.

“The cycle time is accelerating.”

THE CENTERING PROCESS

Of course, to say that you want to revolutionize liberal arts education is one thing; actually doing it requires substantial elbow grease. The first four CLA fellows were appointed in January 2014: they included Popper and Tracy as well as English Professor Deborah Morse and Hispanic Studies Professor John Riofrio. Paul Mapp (history), Carey Bagdassarian (chemistry), Bruce Campbell (German studies) and Georgia Irby (classical studies) followed nine months later. By May of last year, four more had joined the cohort. The fellows, Tracy says, were selected carefully for their balanced commitments to teaching and research, and their passion for collaboration. The interdisciplinary atmosphere is apparent even in their “task-oriented” CLA meetings, he says.

“The conversation just flows freely,” says Tracy. “You need someone as a fellow who is comfortable with that. They don’t need to be the person in the room if they’re recognizing that there is something they can learn from people in other fields.”

Deborah Morse, who just finished a successful pilot of the COLL 200 “Victorian Animal Dreams,” is adapting her research into another course anchored in Arts, Letters and Values, but now stretching further, to Natural World and Quantitative Reasoning. To do so, she’s taking her work on the portrayal and personhood of animals and connecting it with anthropology, history, biology and neuroscience.

“Whole communities are buying into it, and the fact that it is interdisciplinary and that people are thinking of new ways to work with other people. People are recreating their courses in ways they never thought they could before,” she says. “I mean, people really do feel less enclosed in their silos.”The CLA also supports faculty in bringing some of their best research into their COLL classes. Fellows have explored connections between visiting campus speakers and syllabi in various disciplines. Weekly meetings over coffee with faculty helped the fellows explain and develop the idea of the COLL curriculum with departments all over campus.

“The liberal arts is, in fact, going to be necessary to navigate the coming world.”

“Just having four [CLA] fellows and starting everything up was so intense that we were spending 30 hours a week [on COLL],” says Morse. “Honestly, people do it for the love of the College — because they want to be part of something so dynamic.”

Faculty, then, model the qualities the COLL curriculum aims to instill in students: connecting disciplines and thinking hard about how facts and perspectives relate to each other. It’s as if the general education curriculum has been flipped on its head: instead of using core topics to teach analysis, insight and process, COLL brings big questions and cross disciplinary linkages to bear on well-known facts and classic texts.

“With the College Curriculum, our undergraduate students find themselves at the center of an integrated intellectual experience that embraces the skills and habits of a lifetime,” says Arts & Sciences Dean Kate Conley. “Fellows in the Center for the Liberal Arts have provided crucial leadership as we shape a new vision for our liberal arts education.”

In Paul Mapp’s COLL 100, “Idea of Liberal Arts Education,” for example, freshmen learn about the fall of France in 1940 and the ascents of de Gaulle and Churchill through the lens of Platonic ideals and St. Augustine’s The City of God. In Gene Tracy’s “Cosmology and the History of Wonder,” it’s a discussion about free will connecting to black holes and dark energy. It’s rewarding, but not easy stuff.

“I was bringing a lot of material in this semester, so that’s been a lot of work,” says Tracy. “But it’s been a lot of fun. I’ve learned a lot, and had some really good conversations in class. They’re different from the kinds [of questions] that you would have in a traditional survey class.”

For the COLL 100s and 150s (a seminar-style course focused on written and oral communication skills), the point was always to reach students when they were most receptive.

“I think there are a lot of folks, during their first year of college, who are really asking these questions about ‘who am I?’ and ‘what am I going to do?’ and it’s not hard to turn those questions into ‘what is education?’ and ‘what is its role in my life and other people’s lives?’” says Mapp. “So I think they’re especially receptive.”

Mapp says it’s important to catch them while they’re “still enthusiastic and wide-eyed, not jaded at all. To really use that enthusiasm to build up a foundation they can work off for the rest of their four years.” Because this William & Mary education is intended to last. It has to.

ENERGY IN THE ROOM

When Republican presidential candidate and former Florida governor Jeb Bush said in October, “It’s important to have liberal arts … but realize, you’re going to be working at Chick-fil-A,” the education world listened. And they weren’t happy.

In a national climate where state governors are threatening to fund only the academic programs that directly relate to specific job fields, they ignore too many of the liberal arts at their own peril.

“If the sciences are hermetically sealed off from the humanities or the arts, even Einstein said it eventually becomes sterile,” recalls Gene Tracy. “The liberal arts are trying to avoid that sterility. Science is a human activity, and for a lot of people, that’s what makes it interesting.”

In “Cosmology and the History of Wonder,” Tracy utilizes the historical moments of Kepler, Copernicus and Galileo to illuminate the scientific questions at hand. Doing so, he says, helps engage the students in his course who aren’t going on to careers in physics. “There’s more energy in the room,” he says.

To expand on that idea, Popper and physics Professor Marc Sher are working together on a COLL 200 “Historical Perspectives on Science” course that combines their two disciplines — right there in the course title. It’s a perfect example of why Popper thinks of COLL as “an engine of constant circulation.” The structure of the curriculum is set up to accommodate new ideas and opportunities as they arise.

Jamie Leach ’17 has been a part of COLL’s implementation, assisting Sher with updating “Modern Physics,” the first course for any new physics major. The course often presented a stumbling block when it introduced quantum mechanics and relativity. Adding some historical personality helped to bring the material into focus, he says.

“It’s definitely apparent that [history and physics] are two very different ways of looking at the world,” says Leach. “Even when you talk to people who say they see the value of the other discipline and that they can respect it, there’s sort of a distance between them.

“I think there doesn’t need to be. If you take the time and think about these sorts of things, it’s not really that difficult to train your mind to think using other systems of analysis.”

Those skills — learning how to approach learning — will help us ask the future’s tough questions: How will we install lifesaving algorithms in a self-driving car, or determine the role of surveillance technology in smart phones? Connecting math, science and engineering with philosophy, history and sociology will be critical for the workforce of tomorrow.

“That’s why we don’t call what we do training, we call it education,” says Tracy. “We’re trying to promote lifelong learning rather than training you for a particular job.”

And for literally everyone on the planet, the benefits that a broad and sophisticated education carry for our lives as friends, spouses, family members and citizens cannot, and should never be, undervalued.

A STRONGER STUDENT

By the end of the semester, it seemed to be working. Students have responded positively, connecting the lessons, questions and perspectives to their own lives in productive and enlightening ways. And they’re not the only ones impressed. The Association of American Colleges and Universities singled COLL out as a pioneering example of placing liberal arts back at its rightful place at the center of a student’s education. In 2014, the Mellon Foundation granted William & Mary $900,000 to implement COLL over four years. The enthusiasm is spreading.

“We’re always going to face crises, and in fact life may be more tumultuous in the next century than it has been in previous centuries,” says Mapp. “The education that people got 50 years ago or 2,000 years ago in many ways, does provide human beings with the kind of resources that they need when these crises come.”

“Liberal arts education connects the heart to the mind, and heart to heart, and mind to mind,” says Tracy. “That’s what people need to live meaningful lives.”