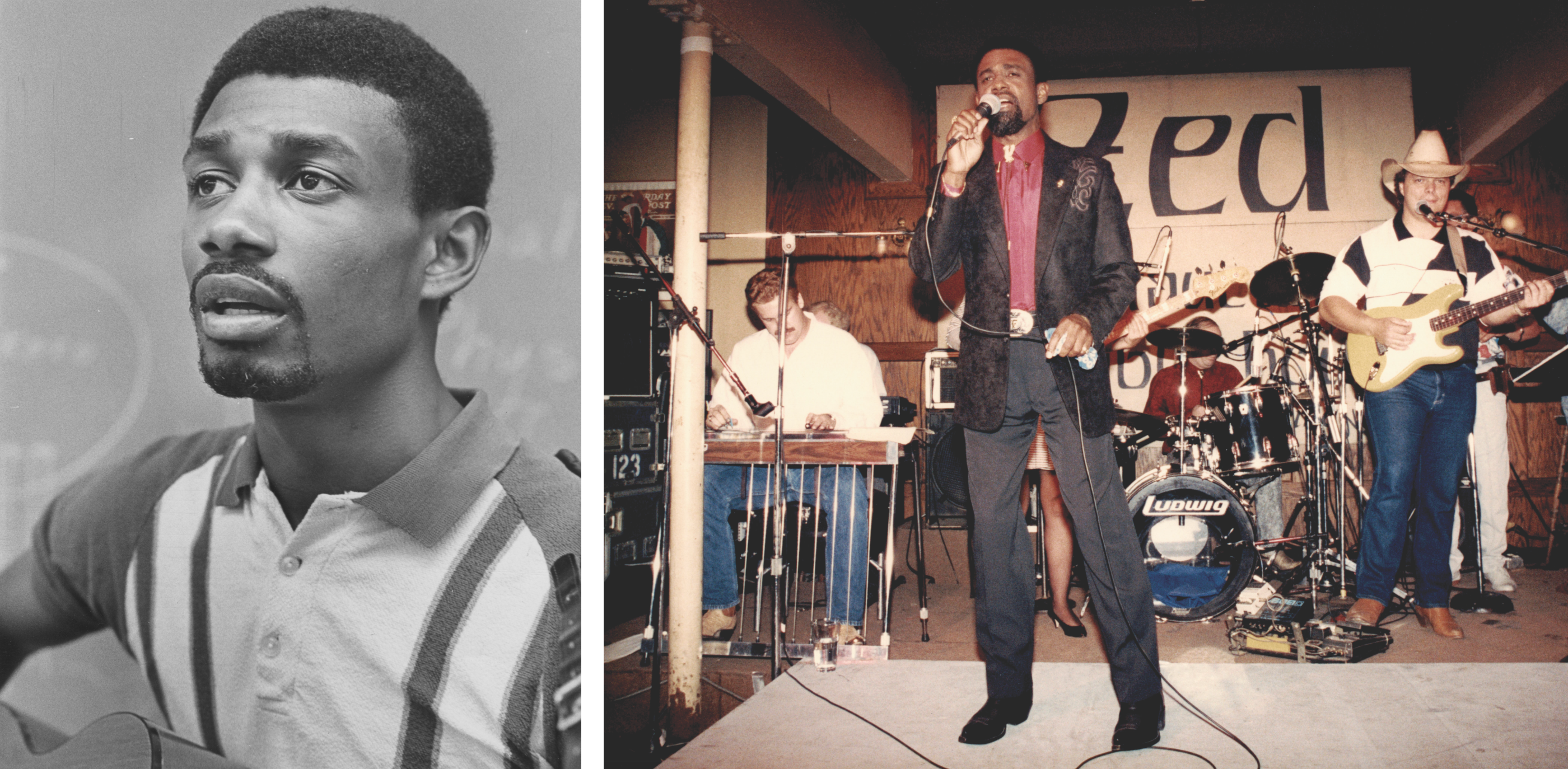

For cardiologist and Nashville recording artist Cleveland ‘Cleve’ Francis Jr. M.A. ’69, William & Mary marked a turning point

Heart & Soul

For cardiologist and Nashville recording artist, Cleveland “Cleve” Francis Jr. M.A. ’69, William & Mary marked a turning point

January 18, 2023

By

Tina Eshleman

In the Southwest Louisiana community where Cleveland “Cleve” Francis Jr. M.A. ’69 grew up, the path to town led through a nearby landfill. At times, smoke from burning trash blew soot onto the clothes his mother had hung out to dry. Railroad tracks marked the dividing line in the racially segregated town of Jennings. The all-Black high school, named after Confederate leader Jefferson Davis, received hand-me-down books with missing sections and writing on the pages. Francis watched his mother, Mary, walk seven miles to work as a maid, and his stepfather toil as a day laborer.

Alongside these stark realities, Francis absorbed the rich musical culture for which Louisiana is known — gospel, blues, jazz and zydeco — and listened on the radio to Sam Cooke, Elvis Presley, James Brown, Mahalia Jackson, Johnny Mathis and others.

“Everybody had some kind of musical talent,” he says. “I knew people who played harmonica, banjo, guitar, trumpet and saxophone.”

Lacking money to buy an instrument of his own, he made a makeshift guitar using one of his stepfather’s cigar boxes. He cut a hole in the middle, fashioned strings from window-screen wire, crafted a neck using a board and taught himself to play.

Impressed by her son’s resourcefulness, Mary Francis saved spare coins for a year to buy a $25 Sears & Roebuck Silvertone six-string guitar. However, she warned young Cleveland — nicknamed Cleve — that if his grades started to drop, the guitar would go up in the attic.

Music became Francis’ respite. He would sit for hours under the giant weeping willow tree in their yard, playing his guitar and writing songs. More than a decade later, while he was pursuing a graduate degree in biology at William & Mary, those memories inspired the song “The Willow Tree” on an album he recorded in 1969 called “Follow Me”:

When the world’s against you and you’re down and out … you just follow me and you’ll see there’s peace beneath the willow tree.

The late W&M sociology professor Victor Liguori, a mentor who recognized Francis’ talent as a musician after hearing him play at the campus pub Hoi Polloi, pooled funds with his colleagues to pay for a recording session in Norfolk, Virginia, resulting in the production of about 250 copies of the album. These came out after Francis graduated from William & Mary, and he sold them at periodic performances while attending medical school at Virginia Commonwealth University. He labeled the album’s style “soulfolk,” combining elements of different genres and including his own compositions as well as songs by Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot and the Beatles.

Although music took a back seat while Francis completed medical studies and established his cardiology practice in Northern Virginia, he has returned throughout his life, metaphorically, to that willow tree back home in Louisiana.

In the late 1980s, a chance encounter with a patient’s family member sparked a series of events that led to a recording contract in Nashville, Tennessee. Francis took a leave of absence from his clinic to explore an alternate career as a professional musician.

The anomaly of a Black man performing country music attracted a wave of media coverage. Former NBC “Today” show host Katie Couric interviewed him in 1992, and his story was highlighted in The New York Times, USA Today, People and Jet magazines, Entertainment Weekly and other publications.

All the positive publicity did not translate into widespread album sales, however. After three years, Francis returned to his medical practice, feeling as though the odds were stacked against him and he’d never attain the level of mainstream success he wanted.

Today, it’s apparent that he made more of an impact through his music than he previously realized.

One of his country albums, “Walkin’,” is on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened in 2016 in Washington, D.C. At a 2021 event celebrating the contributions of people of color in country music, the Rosedale Collective — a label dedicated to cultivating and promoting underrepresented voices in country, folk and Americana music — presented Francis with its first Hazelhurst Award in recognition of his influence. He was also honored with the Black Opry Icon Award in 2021.

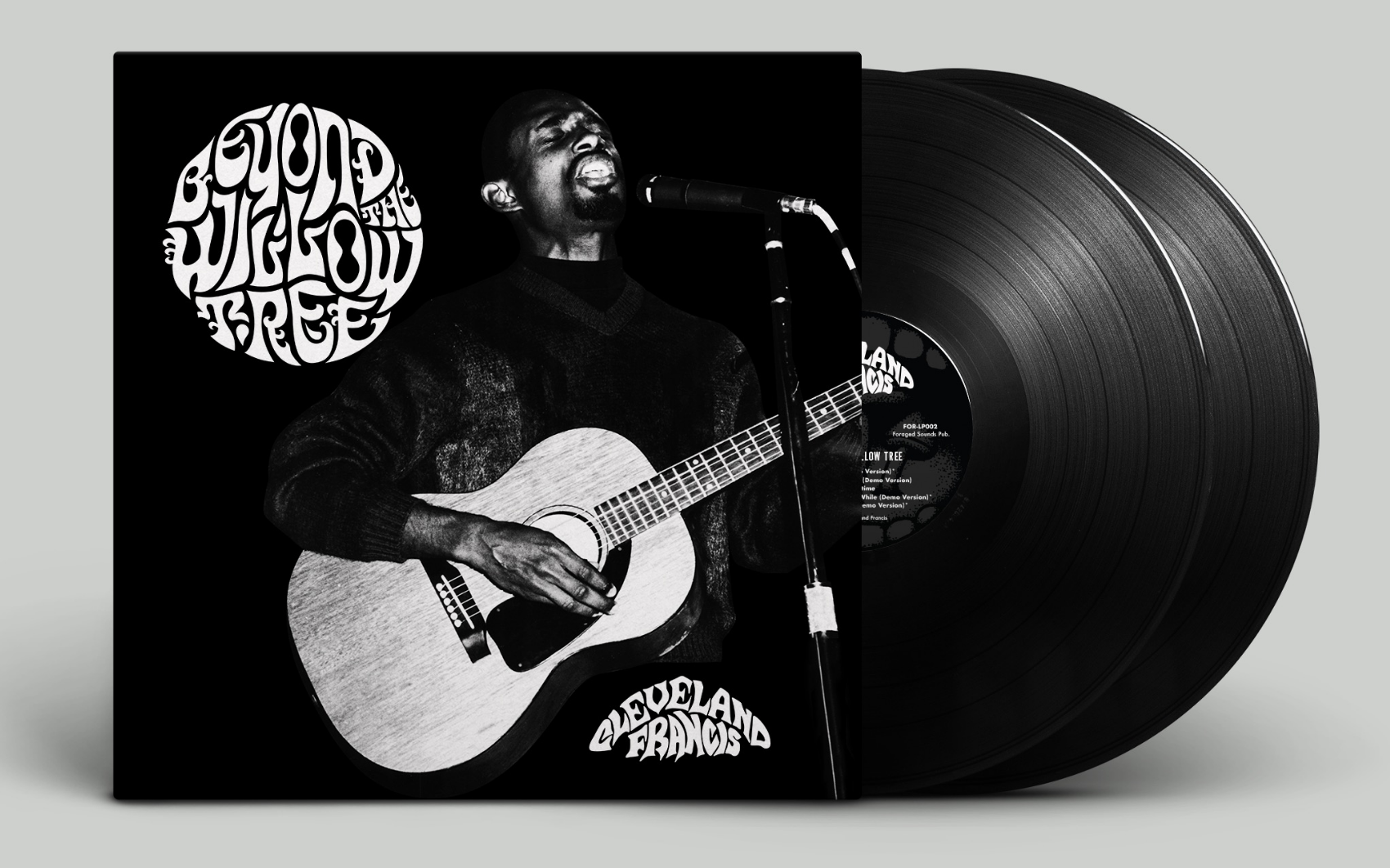

In June 2022, Los Angeles-based Forager Records re-released Francis’ 1969 recordings in an anthology titled “Beyond the Willow Tree,” hailed by reviewers as a little-known gem. A July 2022 article in The Washington Post highlights recent acclaim for Francis and quotes fellow musicians describing him as an inspiration and visionary who was instrumental in founding the Black Country Music Association and convened one of its first meetings. You can also hear Francis tell his story in the podcast "The Show on the Road," hosted by Z. Lupetin of American roots ensemble Dustbowl Revival.

Seeing the re-release of the album he recorded as a graduate student at William & Mary was an emotional experience for Francis, now 77.

“I was almost in tears because it impressed me how significant that music was to people back then — and that those songs I was writing would interest people today,” he says. “I was also impressed by Victor Liguori’s vision. He said, ‘You have to record some of this.’ If he hadn’t insisted, I probably wouldn’t have done it.”

LESSON I: ‘LEARN AS MUCH AS YOU CAN’

It was something of a coincidence that led Francis to William & Mary.

His mother, the daughter of sharecroppers, had to leave school to work in the fields when the harvest came in, so she only learned to read and write at a fifth-grade level. But she saw education as a path out of poverty and was determined that her children would follow it. She also imparted her own wisdom, which her son calls “Mary’s Lessons.” One often-repeated saying was “Learn as much as you can.”

In addition to his love for music, Cleve Francis was always drawn to science.

“I thought I would be a high school biology or chemistry teacher in my hometown,” he says. “They were the ones who lived in the better houses.”

As a high school student, he participated in science club and once traveled to Baton Rouge with his teacher and two classmates for a statewide science competition. On the way back, the teacher wanted matches for his cigarettes and they stopped in the town of Opelousas. Francis offered to run inside a small bar and pick up a penny pack. Ignoring the “whites only” sign, he popped in and asked a waitress for matches, but soon found himself blindsided by a punch in the face from a male patron.

When he returned home, bloodied and shaken, his mother asked him what he thought was an odd question: “If the man who hit you fell into a well, would you pull him out?” He thought about this for a while, and said yes, he probably would. Relieved, Mary Francis left the room. The incident illustrated another of her lessons: “Don’t let hatred control your life.”

“My mother did not want me to become an angry man,” Francis recalls in a draft memoir he’s writing. “I needed to keep my eyes fixed on my future.”

The oldest child and first in his family to attend college, Francis enrolled in Southern University, an all-Black school in Baton Rouge, with funding from the National Defense Education Act.

During his freshman year, he came down with a sore throat and went to the student health center, where he was surprised to see that the doctor, a man in his 80s, was Black. Back in Jennings, there were no doctors’ offices available to Black residents, and the closest hospital where they could receive treatment was 50 miles away.

“I was totally amazed,” he says. “I didn’t even know you could do that. I said, ‘That’s what I’m going to do.’ I went in and changed my major from biology education to pre-med biology just like that.”

After switching to pre-med, Francis met an influential professor, Director of Music Huel Perkins, through a required humanities course. One day, Perkins challenged his students by asking them what talents they could share with the university community. He invited each of them to make a 15-minute appointment so he could see or hear their contribution.

Francis brought his guitar to the appointment and started to play. Halfway through the second song, Perkins told his secretary to cancel the rest of his appointments and bring in a tape recorder. He then asked Francis to play a concert for the music department.

“You’re a folk singer,” Francis recalls Perkins telling him. “You’ve developed a natural style. What you’re doing is unique.”

Noticing that Francis’ guitar was cracked, Perkins took him downtown and bought him a new one. The professor kept the old Silvertone guitar until his death in 2013. Francis sang at Perkins’ funeral and then brought the guitar back with him to Virginia.

Despite his standing as a good student at Southern University, Francis received rejections from all 12 medical schools he applied to, not anticipating that racial discrimination would be a factor at medical schools outside the South.

“It was devastating,” he says. “Then the reality hits you — maybe they didn’t consider you at all.”

Francis started to think he would have to return to his earlier plan of teaching biology, but his dream was to practice medicine. Drawing on his Baptist upbringing, he prayed and asked God for help. Not long afterward, while walking in the biology building and pondering what to do, he noticed a prepaid postcard from William & Mary on the door of the department offices seeking applications for graduate studies in biology. He took it back to his room and left it on his desk for a couple of days.

Although he didn’t know anything then about W&M, he says, “I thought, ‘What do I have to lose?’ I ended up putting it in the mail and that would change my whole life.”

When he received notice of a package two weeks later, he thought it might be cookies from his mother. Instead, it was a syllabus and application. He filled it out and after another couple of weeks, received a letter of acceptance.

“I read in the library about Thomas Jefferson and all the great people who went to William & Mary,” he says. “I saw that it was one of the oldest academic institutions in the country. I said, ‘I’m going to go and see what it is.’”

With a graduate degree from William & Mary, he thought, perhaps he would have better luck getting into medical school.

LESSON II: ‘PEOPLE WILL HELP YOU IF THEY SEE YOU ARE ABOUT SOMETHING GOOD’

Francis arrived in Williamsburg at 5 p.m. on a Saturday in the fall of 1967, carrying his guitar and a small brown suitcase, after traveling by train from New Orleans. As he stood at the Williamsburg train station wondering which way to go, a car pulled up and honked. The driver was a white woman whom he’d helped with her bags when the train stopped in Richmond. To his surprise, she asked if he needed a ride — something he’d never experienced in Louisiana.

“Williamsburg was a whole new world,” he says. “The town was still racially segregated, but not as oppressive as in Louisiana.”

He said he wanted to go to a Black church, and the woman drove him to First Baptist Church on Scotland Street, where he planned to seek help finding housing. As it turned out, the minister, the Rev. David Collins, was also from Louisiana and invited Francis to share his house. The two became friends, and Francis began singing in church, just as he had back home in Jennings, where the first song he played in public was “Amazing Grace.” Members of the congregation welcomed him into their homes.

“They were very proud of me for coming to William & Mary,” he says.

Despite being one of just a handful of Black students at the university — the first three Black residential undergraduate students also arrived in 1967 — Francis says he felt welcomed by the biology department faculty and his fellow students.

His faculty adviser was Garnett R. “Jack” Brooks, now a professor emeritus, who specialized in herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians.

“He was very kind and understanding, and guided me through my research,” Francis says. “One of my jobs as a graduate assistant was to make sure that the snakes were fed. I overcame my fear of snakes and acquired a small boa constrictor as a pet.”

During Francis’ second year of graduate school, he and fellow biology student David Gapp ’67, M.S. ’70 shared an apartment and began a friendship that continues today. After being turned away by a white-owned rental company that the biology department secretary had contacted beforehand on their behalf, the two found a Black landlord who was willing to rent to them. Gapp, who is white, says he was dumbfounded by the rental office’s response, but Francis took it in stride.

“Cleve taught me to be a better person,” Gapp says. “He helped me to understand the experience for Black people as it was then, and as seen through the eyes of someone who grew up in Louisiana.”

Gapp recalls that Francis started performing music at bars and coffeehouses in the area not long after arriving at William & Mary. Along with music by folk groups such as Peter, Paul & Mary, Francis would play songs by Hank Williams and Glen Campbell.

“He became a celebrity pretty quickly — everybody knew Cleve,” Gapp says.

During the summer of 1968, Francis talked Gapp into performing with him after learning they could make more money as a duo — $50 per night instead of $25 — which would help with their rent and grocery expenses.

“I thought it was a horrible idea,” Gapp says. “I had picked up the guitar as part of the folk craze of the ’60s, and I was remarkably mediocre. But Cleve pushed, and I said OK. So we started practicing together.”

Performing as Cleve and Dave, they were featured on television station WAVY-TV and made appearances around town, culminating in a standing-room-only show at William & Mary’s Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall on Valentine’s Day in 1969. Among the songs from that set were Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now,” Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay” and Francis’ original composition “The Willow Tree.” The appreciative crowd gave them a standing ovation.

“The music was gentle,” says Gapp, a retired Hamilton College biology professor living in Maine. “It wasn’t strident at a time when there was a lot of strident music. Even when he sang about protest, it was not harsh.”

Gapp played on the album Francis recorded at Studio Center in Norfolk. Bruce Grant, then a new biology professor, provided the bass line on the single “The Willow Tree,” but he bowed out when the project expanded.

“I could hear them practicing from time to time,” Grant says. “When they learned I played guitar, too, they invited me to join them. We became friends. But I was very busy as a brand-new faculty member, so when they became more ambitious about making an entire album, I knew that would require far too much time than I could spare.”

Francis then recruited Kenneth Zeigler, a teenager who was dating his younger sister, Nancy, to play bass on the recordings. By then, Francis’ parents had separated and he had helped his mother and two youngest siblings move to Williamsburg. His mother worked as a waitress at some of the area’s higher-end restaurants until Francis persuaded her to retire, and she remained in the area until she passed away in April 2022.

While at William & Mary, Francis says he found the right audience for the music he wanted to play.

“There was never really an avenue to play folk music at Southern University,” he says. “People were listening to the Temptations and James Brown, and I was sort of a closet folk musician.”

Francis wanted to tell stories and provoke conversations during a time when students were protesting the Vietnam War and becoming active in civil rights.

“The intent was not to dance but to sit and listen,” he says. “Folk music was a cultural force and I was in it.”

One of the songs in “Beyond the Willow Tree” responded to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Francis heard the news of the civil rights leader’s death while driving back to Williamsburg with Gapp after they’d spent spring break at the home of Gapp’s family in Northern Virginia. They didn’t say a word the rest of the drive, and Francis wrote “Ballad of Martin Luther King” upon returning to their apartment.

LESSON III: ‘YOU MUST BE WILLING TO TAKE A FEW STEPS IN THE DARK’

Having earned a master’s degree in biology from William & Mary — he later received membership in the Omicron Delta Kappa honor society — Francis was accepted into the VCU School of Medicine (formerly the Medical College of Virginia). There, he was one of just two Black medical students. The other student, Archer Baskerville, became his roommate, and through Francis, Baskerville met a William & Mary student whom he later married, Viola Osborne Baskerville ’73.

After medical school, Francis completed a fellowship at George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C., but then found job opportunities lacking at hospitals and established medical practices.

“Although it was 1973, a lot of white practices didn’t feel comfortable with Black associates,” he says. “That was shocking to me that we were still at that point.”

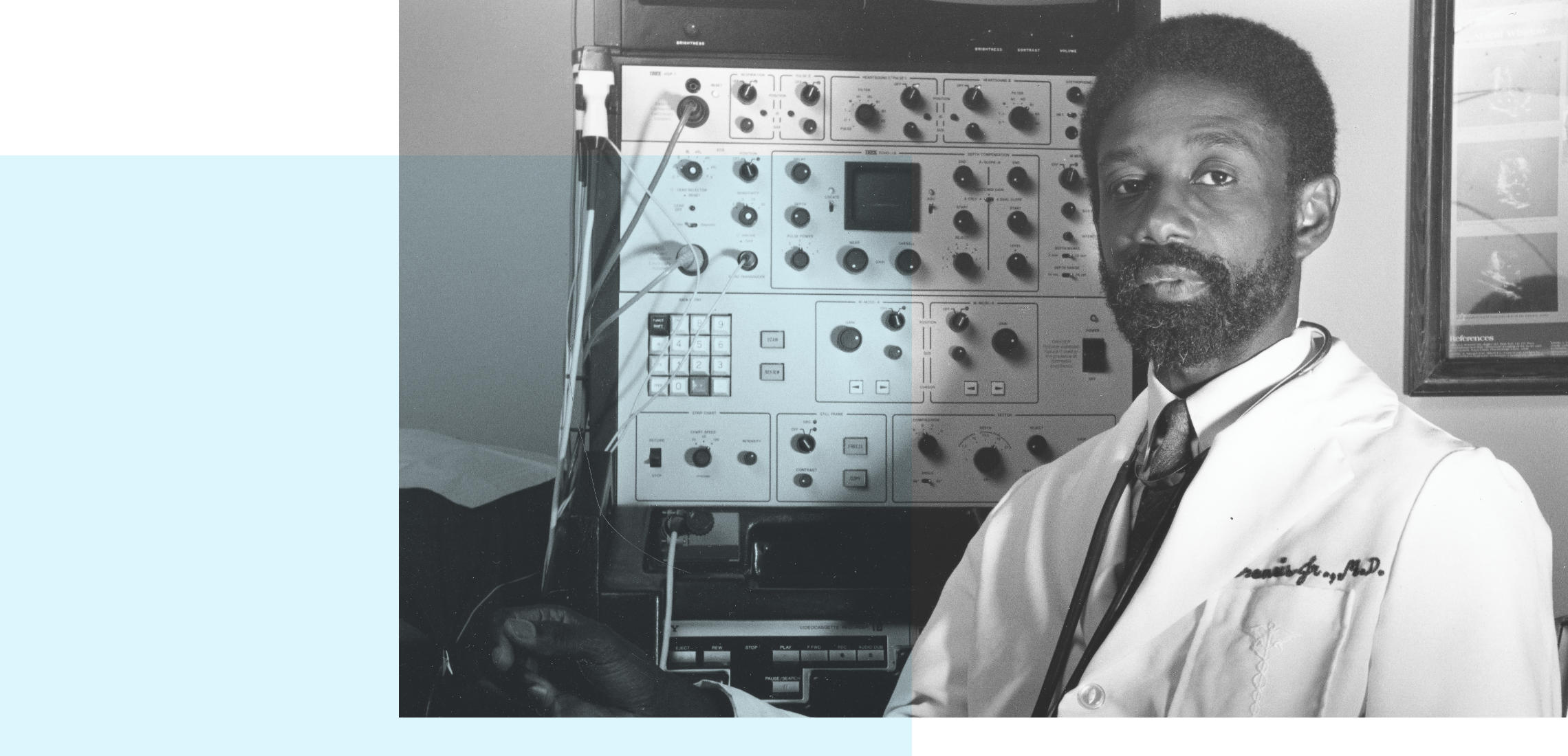

Francis then decided to start his own practice, Mount Vernon Cardiology Associates. He obtained a $30,000 line of credit — a daunting amount for him at the time — and established a multicultural, multilingual practice.

“It was a prototype and it was very successful,” he says. “People would seek us out.”

One weekend in the late 1980s, Francis was on call for the cardiology group and wound up in a hospital critical care unit treating a patient who’d had a heart attack. After monitoring the patient throughout the night, Francis met the man’s brother, John Hall, who arrived from Florida in the morning and happened to be a professional musician.

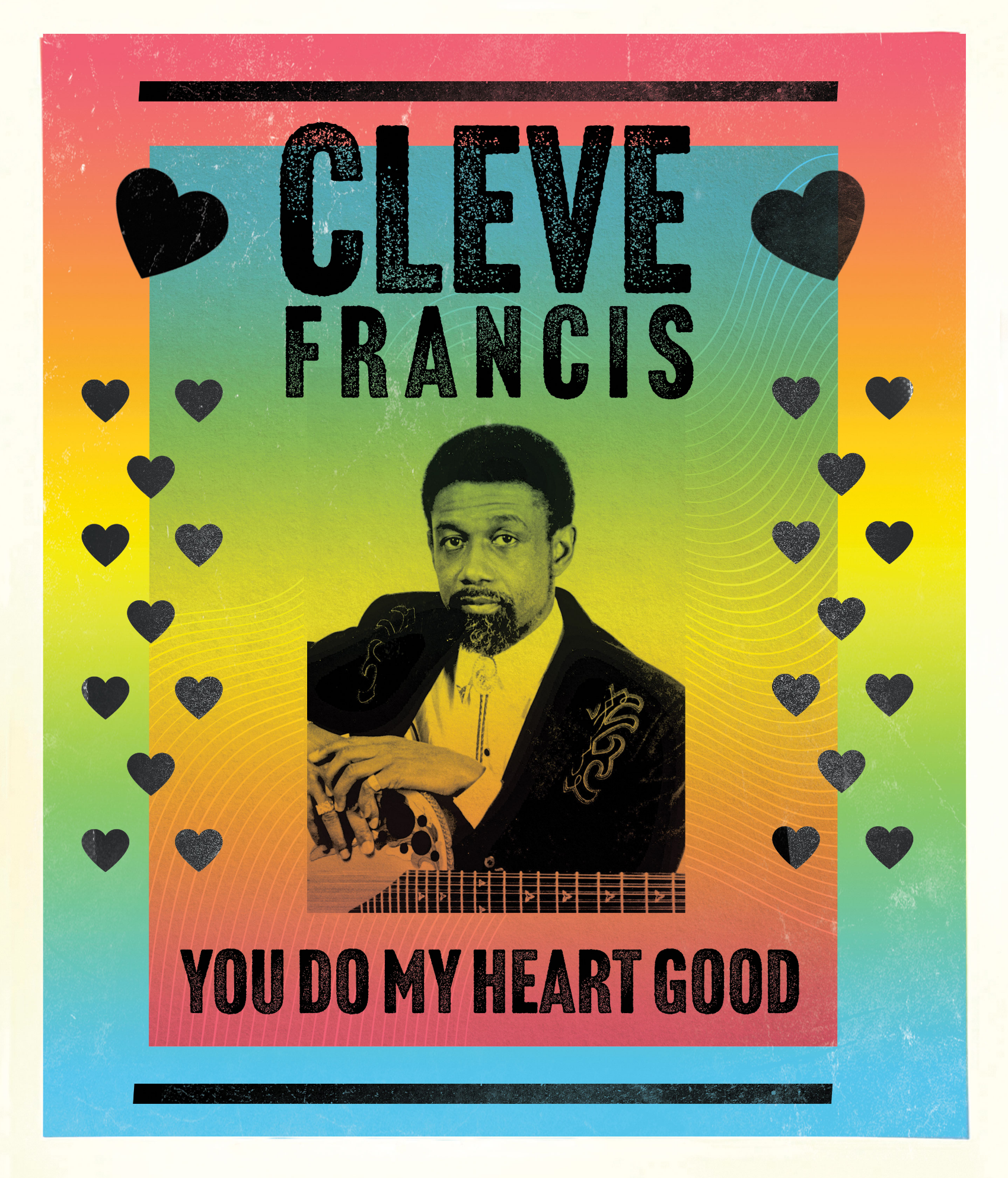

When he learned that Francis played music, Hall asked to hear it. Francis gave him a cassette, which he then passed along to Jack Gale, president of Miami-based Playback Records. Gale later contacted Francis and they recorded an album titled “Last Call for Love” featuring the single “Lovelight,” the B-side of Glen Campbell’s “Rhinestone Cowboy.” Francis hired a young filmmaker to produce an accompanying video for “Lovelight” that became a hit on Country Music Television, peaking at No. 9, and was named MusicRow Magazine’s Independent Video of the Year in 1990.

Record executive and producer Jimmy Bowen noticed the video on TV after playing golf one day and flew Francis to Nashville, where he was offered a three-year deal in 1991 with Liberty Records (now Capitol Records Nashville).

Francis talked it over with friends and his practice partners, who encouraged him to go for it. He was single, since his first marriage ended several years earlier, and had no children, so he felt it was as good a time as any to make a leap of faith.

Soon, he was performing around the country, appearing at the Country Music Association’s Fan Fair and the Grand Ole Opry and traveling to England, Scotland and Canada.

But after three years, he felt he’d gone as far as he could. He had not been able to get his music played on country music radio or join the kinds of big-name tours that would have boosted his career — something he attributes in large part to the industry’s lack of openness to diverse performers at the time.

“If you could get on a Garth Brooks tour, you’d play 15 minutes before he comes out and you’ve got 100,000 people there,” he says. But Francis never had that opportunity. Some venues were not open to having a Black artist perform, he says. “It wasn’t a fair playing field. I was never allowed to demonstrate my talents.”

By then, he adds, “I was older and country music was changing to a younger demographic. If I hadn’t made it by then, I wasn’t going to make it.”

Based on his own experience, Francis saw the need for a trade organization that would spotlight the music of Black artists, act as a liaison to record labels and create opportunities for performers to reach a wider audience. His vision led him to form the Black Country Music Association in 1995. After Francis left Nashville, singer Frankie Staton moved the organization forward and began holding Black country music showcases. As described in Rolling Stone magazine, “in the late ’90s and early 2000s, the BCMA blossomed into a thriving community of Black Nashville artistry.”

When Francis returned to his cardiology practice, he continued playing music on the side.

“I promised my mother that I would never get to a situation where I would put my medical career in jeopardy after all she had done and I had done,” he says.

Through televised competitions and platforms such as YouTube and TikTok, there are more avenues for Black country musicians to reach an audience these days, Francis says. And even though things didn’t turn out as he had hoped in Nashville, he is remembered as one of the most high-profile Black country music artists after Charley Pride in the 1960s.

“Growing up and learning about all the different country artists, especially the ones that look like me — from Charley Pride to DeFord Bailey before him — I heard about Cleve Francis,” Jimmie Allen, who won the Country Music Association Award for New Artist of the Year in 2021, told The Washington Post. “He was definitely one of those artists I wish would have gotten the recognition he deserved, but he touched many people’s lives that he probably didn’t realize, including mine. Cleve’s definitely one of my inspirations.”

LESSON IV: ‘STAND FOR SOMETHING’

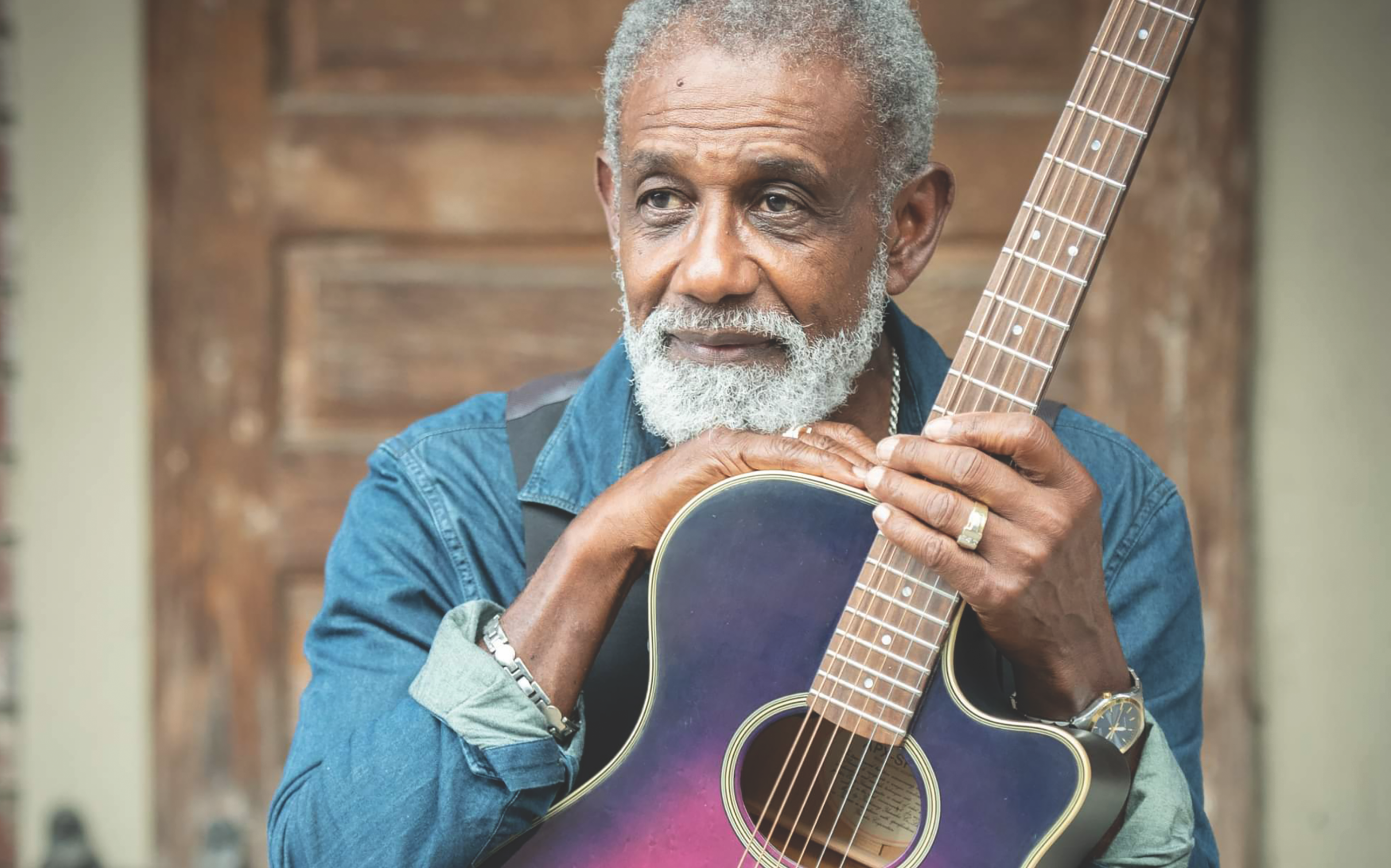

Francis sold his medical practice to Inova Health System in 2015, and retired from seeing patients in 2021. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with his wife, Hardeep Francis, a since-retired health care quality consultant who has been supportive of her husband’s medical career and musical pursuits. Her passion for birding and landscape photography has taken the couple around the country and overseas.

Cleve Francis remains involved on a part-time basis as diversity advisor for the Inova Heart and Vascular Institute. He founded an Inova Health System program called Dream Big to introduce teens from underserved areas to career opportunities available in health care systems.

“My interest is increasing the pipeline of Black health professionals by working with young minorities in elementary and high school,” he says.

Just as he did when he was at William & Mary, Francis writes songs inspired by current events — most recently the single “Buffalo,” responding to racially motivated killings in New York state. He performed “Martin,” another song he wrote commemorating Martin Luther King Jr., in 1985 in Atlanta for the 22nd anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Along with Francis, a recorded version features vocals by Patti Austin, Ollie Woodson, Daryl Coley, Vanessa Williams, Yolanda Adams, Cybill Shepherd, Claude McKnight, Will Downing, Jackie Johnson, Kelli Williams and the National Civil Rights Museum 25th Anniversary Mass Choir. Francis also wrote “Reflections on the Wall” in 1987 by request for a ceremony at the Vietnam Wall dedicated to those who fought in the war.

Before the pandemic, he played at the Birchmere in Alexandra once a year, usually accompanied by a 12-piece band. He hopes to return to the stage soon, perhaps in a pared-down setting with just a guitar and a microphone.

“I feel very lucky,” he says. “That’s why I’m anxious to tell my story. I hope to inspire kids who start out in a similar situation to see that with will and determination, they can do anything.”