History in Hindsight

Crowd-sourced database project coordinated by Eric Schmalz ’10 reveals what Americans knew about the Holocaust at the time

June 9, 2025

Profiles By

Tina Eshleman

Photo Illustrations By

Nadia Radic

WARNING SIGNS APPEARED EARLY. THEY WERE EVIDENT TO THE WORLD LONG BEFORE CROWDS AT THE 1936 SUMMER OLYMPICS IN BERLIN DISPLAYED “HEIL, HITLER” SALUTES. BEFORE GERMANY INVADED POLAND ON SEPT. 1, 1939, AND ENGLAND AND FRANCE DECLARED WAR SOON AFTERWARD. BEFORE AIR-RAID SIRENS BLARED DURING THE LONDON BLITZ, AND JEWISH RESIDENTS WERE FORCED INTO GHETTOS IN EASTERN EUROPE. BEFORE MILLIONS OF JEWS WERE DEPORTED TO CONCENTRATION CAMPS IN CROWDED CATTLE CARS.

An editorial in William & Mary’s student-run Flat Hat newspaper on April 4, 1933, sounded an alarm about censorship: “The Hitler government has clamped a rigid barrier upon the sending of news stories to other nations.”

It was just over two months since Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany and began forming a one-party dictatorship. Appearing under the headline “The Pogrom Program,” the Flat Hat editorial followed reports of Hitler’s Nazi Party organizing a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses on April 1, 1933.

While the editorial acknowledged anti-German bias from some of the external news sources, the writer was troubled by the treatment of Jewish citizens and concluded, “There can be little doubt that race hatred in all [its] most malignant forms is rampant in the Reich.” The editorial writer foresaw dark days ahead for Germany: “No nation, people or government can sow the seeds of hatred, bigotry, oppression, persecution and cruelty, and not be called to account sooner or later. The reckoning that they will pay will probably be in the form of bloodshed.”

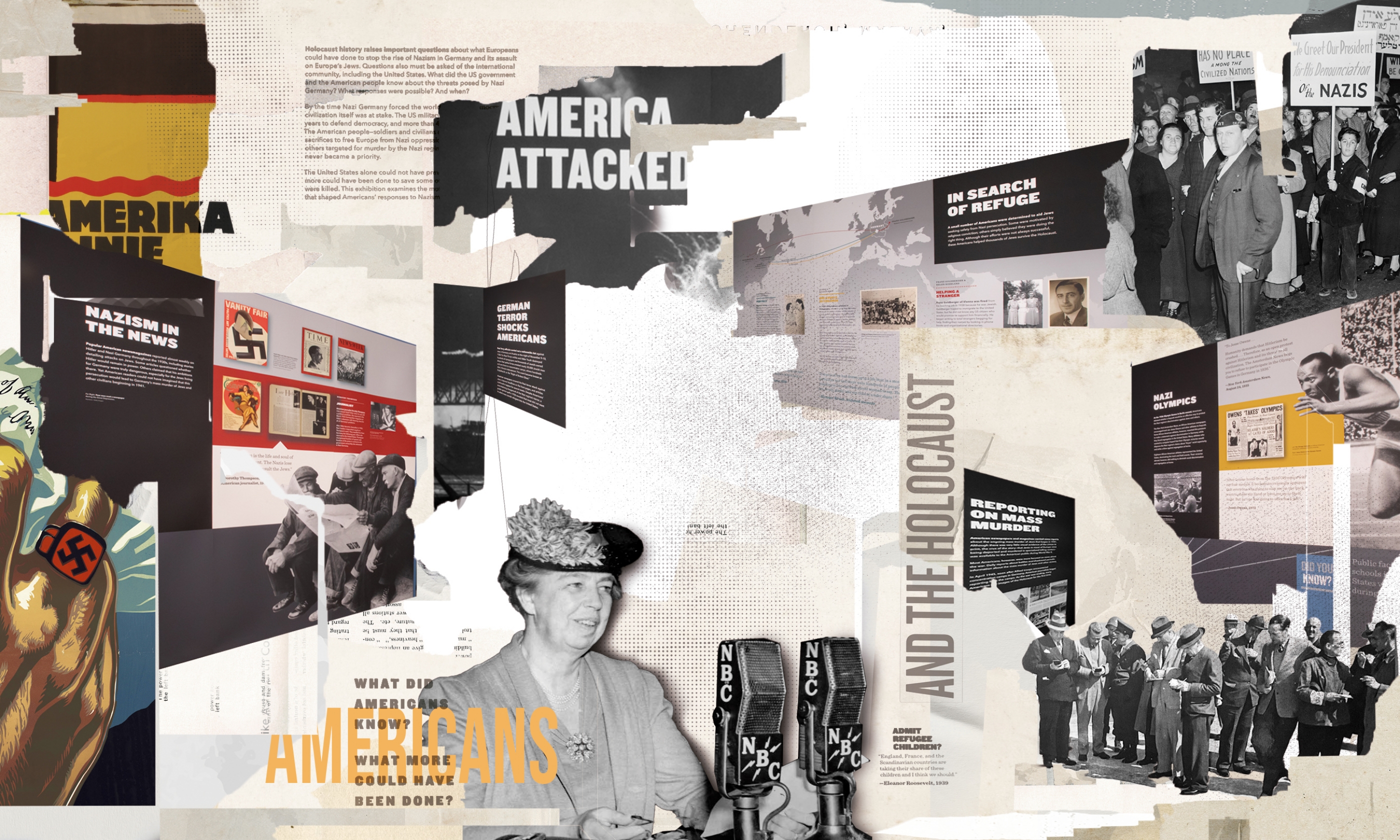

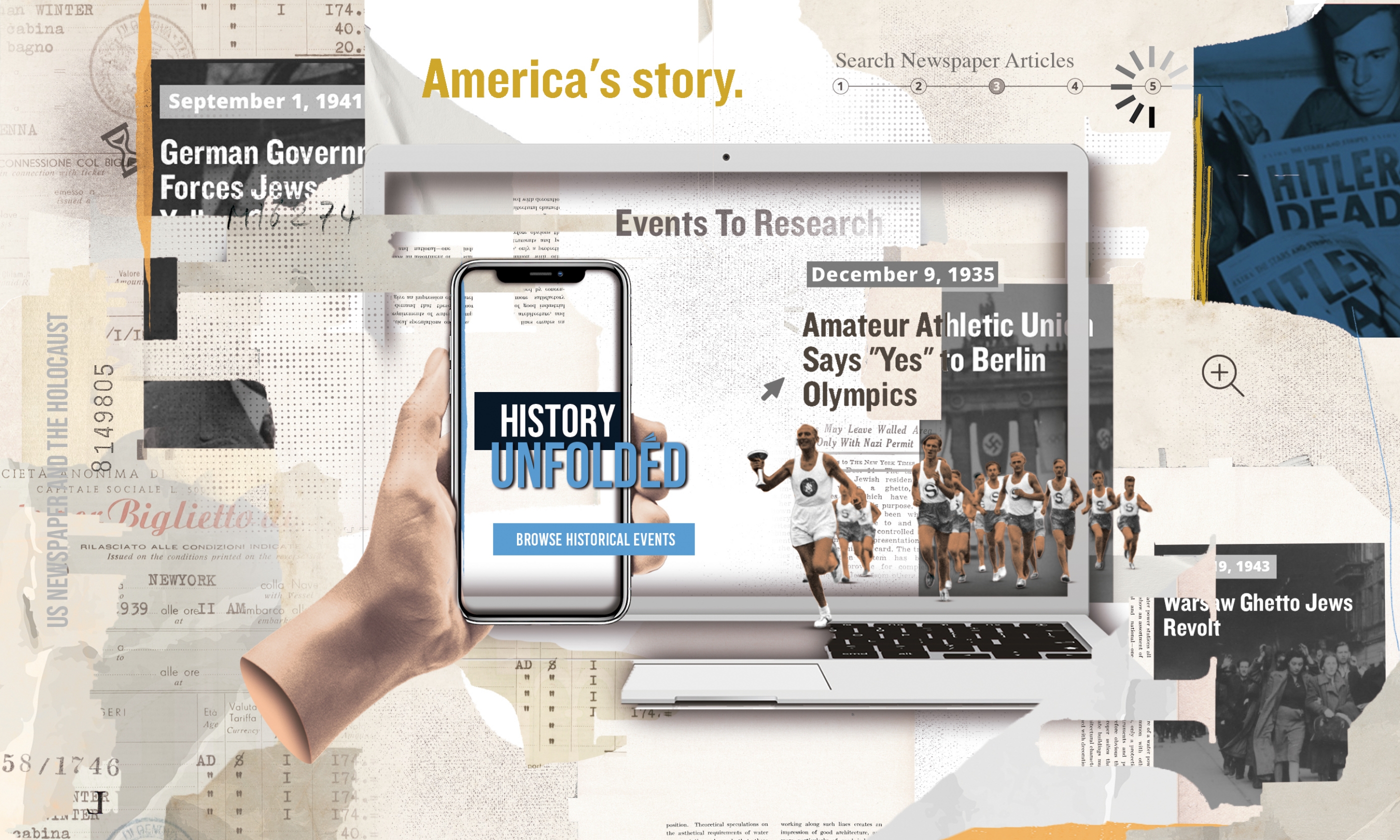

The Flat Hat editorial is one of about 55,700 articles included in a United States Holocaust Memorial Museum project coordinated by Eric Schmalz ’10, a former William & Mary history major and Monroe Scholar. Titled “History Unfolded: US Newspapers and the Holocaust,” the project looks at how newspapers across the country covered specific events in the 1930s and ’40s with the goal of understanding what Americans might have known about the Holocaust during that time.

When the museum launched “History Unfolded,” Schmalz says, “there was a misperception that Americans in the 1930s and 1940s knew hardly anything about how Nazis persecuted Jews until the liberation of the concentration camps, or didn’t have access to that information. The museum wanted to test that hypothesis and ask how local newspapers were actually reporting on this. Up to that point, a lot of research had looked at larger newspapers. But we didn’t know as much about smaller daily and weekly newspapers. The research typically wouldn’t include places like Williamsburg, or like rural Iowa or Alaska.”

Over a nearly eight-year period, more than 6,400 high school and college students and adult citizen historians across the country contributed articles from their community libraries, historical societies and archives. Their research resulted in a searchable digital database at newspapers.ushmm.org. The “History Unfolded” project helped to inform parts of the museum’s ongoing “Americans and the Holocaust” special exhibition in Washington, D.C., and a related traveling exhibition. The project also provided material for the 2022 PBS documentary film “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” directed by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein.

The project, exhibition and documentary provide insights into what people in the United States knew about the threats posed by Nazism. Domestic conditions in the United States, including unemployment during the Great Depression and national security concerns, as well as antisemitism and racism, shaped Americans’ responses, Schmalz says. Now, 80 years after the end of World War II in Europe on May 8, 1945, democratic nations still wrestle with how to respond to international crises — and what their responsibility should be to people displaced by violence and persecution.

The museum avoids drawing parallels to current events, however, Schmalz says: “We find it is much more powerful to present the history and then allow people to draw relevance and make the connections themselves. Our curator of the exhibition often says we don’t tell people what to think, but what to think about. And I love that.”

‘HISTORY FROM BELOW’

As someone who grew up in the Washington area’s Northern Virginia suburbs visiting museums and Civil War battlefields, Schmalz says he’s always been interested in history, but he had little concept of what historians do until he got to William & Mary. “I thought that the way historians did their work was they looked at other historians’ books, and they essentially rewrote them,” he says.

Classes he took with history professors such as Philip Daileader changed that perception: “Professor Daileader would get us to think critically about the past and history, and he would say, ‘If I could create as much doubt in you as humanly possible, I have done my job.’ The notion was to be a critical analyzer of historical documents and not to take anything just immediately on face value.”

Most influential for Schmalz was Lu Ann Homza, the James Pinckney Harrison Chair and Professor of History, who encouraged his interest in early modern European history, church history and Reformation studies. He recalls Homza showing him how to look up original documents about early church reforms on microfilm at Swem Library.

As a Monroe Scholar, Schmalz had an opportunity to spend part of the summer after his sophomore year delving further into the archives at Swem and exploring resources at the Library of Congress and Catholic University of America. The next spring, when he was in a study abroad program in Toledo, Spain, Homza invited him to join her in Pamplona as one of three students doing archival research funded through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

“I was studying the 16th-century church in Spain and some of the issues that parishioners were having,” he says, adding that priests were often absent because they divided their time among multiple parishes. “It was so fascinating. I remember holding those original documents in my hands and thinking, ‘What an incredible experience.’”

Schmalz investigated “history from below as well as history from above,” Homza says. “He could read treatises by important theologians and bishops in Spain in the 16th century, but then he could also go to Pamplona and look at complaints by parishioners in tiny villages about their local priests, and how they really wanted their bishop to step in and help them with a priest who was not saying Mass correctly or who was drinking or gambling too much. That showed a side of Catholicism to him that I don’t know if he had been aware of yet in terms of the challenges that the Catholic Church was facing in those moments in time.”

That research background later helped Schmalz secure a job at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2015 as the citizen history community manager for the “History Unfolded” project. After receiving a master’s degree in education from the University of Virginia, Schmalz taught high school history for about three years. When he read the museum’s job listing, he saw an opportunity to blend his research interests and background as an educator.

“They wanted somebody with teaching experience who had done historical research and knew how to look into archives and databases,” he says. “What I thought was so cool when I saw that job description and when I interviewed was a specific project goal to help develop students’ research and analysis skills — and to foster a love of history.”

Homza sees Schmalz as well suited for his role at the Holocaust Memorial Museum. “It’s the best of both worlds in a lot of ways,” she says. “He gets to do what we call public-facing history and have an impact on the communities with whom he’s communicating, and also still do all the research that he loved to do when he was an undergraduate.”

CROWD-SOURCED RESEARCH

As the museum started to plan the “Americans and the Holocaust” initiative, which would be centered around a new special exhibition, a team of educators at the museum reconsidered the usual pattern of creating an exhibition and then designing educational materials.

“They thought, ‘What if we invited students ahead of time to do authentic historical research in support of a forthcoming initiative? How interesting would it be if we created a program where we had students learn history by doing history, and perhaps some of the research might even be able to be incorporated into the exhibition?’” Schmalz says.

The project initially focused on high school students around the United States, but then extended to college students and adults. Participants researched newspapers on microfilm or online (or original newspaper) archives and uploaded documents to the museum’s database. Schmalz himself researched articles in the Flat Hat and contributed several of them to the museum’s digital database.

W&M History Department Professor and Chair Tuska Benes describes the “History Unfolded” project as “an intensely democratic approach to understanding the past, because it allows voices to come to the forefront that might be overlooked in more traditional approaches that rely on state archives or a top down perspective.”

As part of a summer course Benes teaches at William & Mary on Nazi Germany, she assigns students to look at how American newspapers reported on the emergence of fascism across Europe.

“We’re often struck by the disconnect between the way people were viewing these events as they unfolded and how we perceive them today,” she says. “So it’s often a shock to students to see that reporting didn’t necessarily pick up on what we now recognize as the most significant implications of the historical events as they unfolded. There are major milestones that, retrospectively, we realize indicated an escalation of Nazi racial policy leading up to the mass murders that took place in the concentration camps.”

Among those events were the Nuremberg Race Laws of September 1935, which denied Jews German citizenship and political rights because they were not considered part of what the Nazis deemed the superior “Aryan” race, Benes says.

“At the time, people were trying to normalize that,” she says. “They didn’t recognize just how drastic and pernicious the initiatives were.”

Snow College in Ephraim, Utah, was one of the schools that participated in the “History Unfolded” project. Carol Kunzler, an instruction and outreach librarian there, says the “Americans and the Holocaust” traveling exhibition came to the college in 2023 after being delayed two years by COVID-19. In the meantime, about 70 students participated in research for the project, contributing 160 articles to the database.

Some student researchers looked beyond Utah to other parts of the United States to help Schmalz’s team fill in geographic gaps. During the process, students would sometimes discover names of family members they recognized in sections of the newspapers not directly related to the research. In writing about the project, some of them reported being surprised by the fears and biases they observed in the newspaper articles, Kunzler says.

Kunzler herself looked at newspapers in Indiana and the Midwest, where her ancestors lived during the time of the Holocaust.

“It became a very emotional journey for me, seeing the amount of evil that was going on and Americans not realizing the full extent of what was happening,” she says. “In the exhibition, there was a quote from a soldier who was shocked at the horror of what they were seeing when they finally liberated people in the concentration camps.”

Kunzler was struck by how early Hitler began making changes in Germany before the official start of World War II and how he was able to seize power. She also found it interesting to see how newspapers reported the events.

“In smaller newspapers, there would be a tiny article that was maybe 10 or 15 sentences about what was going on in Germany, while those in bigger cities might have full-page spreads,” she says. “I was surprised, in some cases, by how little attention the events were getting.”

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

In addition to how rural and small-town newspapers covered events, there are also articles from Jewish publications that covered events in more detail and from African American newspapers that made connections to racism and discrimination in the United States, Schmalz says.

Then, as now, Americans wrestled with questions of foreign policy and immigration, with some believing the U.S. should intervene and others taking a more hands-off approach.

Among other topics, researchers looked into news coverage of proposed legislation in 1939 known as the Wagner-Rogers bill, to admit 20,000 German refugee children to the United States.

“Americans as a whole were not in favor of working around that immigration quota,” Schmalz says, noting that the legislation died in the Senate Immigration Committee. Project volunteers found letters to the editor on the subject: “Some people said we should help our fellow humans who are living abroad; others said we should take care of our own children first.”

Opinion writers in the Flat Hat also expressed divergent views at various times. For example, editorial board member Sidney Jaffe ’39 wrote in an op-ed column on March 1, 1938, just before Germany annexed Austria, that “The time has passed for idealism and vague looking toward the future. The democratic countries must decide whether to unite for action or remain as individuals, preaching loudly but incapable of action by virtue of that very individualism. The former course may easily mean the restoration of world order; the latter may mean the domination of fascism.”

On the other hand, an unsigned Flat Hat editorial on March 11, 1941, expressed agreement with U.S. Sen. Burton K. Wheeler of Montana, who opposed U.S. entry into World War II. “There is a determined, organized minority at work using every clever device possible to push us into this conflict,” the editorial states. “We take our stand with the 81% of the American people who, with Senator Wheeler, want to keep peace for America.” It’s worth noting that the Flat Hat’s editor-in-chief at the time, Carl Muecke ’41, later served in World War II as a Marine Corps major who worked with German defectors to spy on the Nazi regime.

While the newspaper project is no longer collecting submissions, Schmalz continues to work with educators to incorporate “History Unfolded” research into their classrooms.

“We are an educational institution, so we want to be able to support teachers,” he says. “That’s something that I’m passionate about.”

Schmalz currently serves as community manager and project lead for the museum’s “Americans and the Holocaust” traveling exhibition tour, which is in partnership with the American Library Association. The exhibition is visiting 100 libraries across the country from 2021 to 2026. It will be at the Virginia Beach Public Library/Tidewater Community College Joint-Use Library through June 28, and the library is partnering with the United Jewish Federation of Tidewater (UJFT) on some of its programming. UJFT’s announcement about the exhibition notes that the organizations involved “aim to deepen a collective understanding of Holocaust history and encourage critical thinking about today’s challenges.”

As people around the world observe the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, “it’s imperative that all of us, as human beings, don’t lose sight of the large impact of the Holocaust and other crimes against humanity,” says Elka Mednick, director of the UJFT’s Holocaust Commission. “As [author and Holocaust survivor] Elie Wiesel said, once you learn a story from a survivor, you become a witness and you become a steward of those facts. So when we read the stories and see the photographs in the exhibition, we all become witnesses. It becomes our responsibility to make sure those stories are not forgotten.”