Restoring the Peregrine Falcon

W&M students restored Virginia’s population of this formerly endangered species

December 4, 2025

By

Catherine Tyson ’20

This story was originally published on W&M News.

Amanda Allen Beheler ’92, M.A. ’95 will never forget the first time she saw a peregrine falcon fly. It’s etched on her soul, she says.

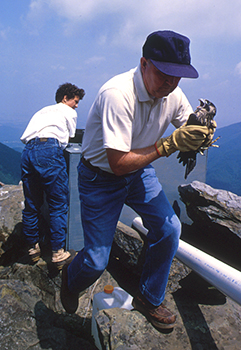

She was one of nearly 20 William & Mary undergraduate students who took part in the Eastern Peregrine Falcon Recovery Team in the 1970s-1990s. Assembled 50 years ago, this group helped to bring peregrines back to the eastern United States after the last breeding pair disappeared in the mid-1960s. Mitchell Byrd, a W&M biology professor and renowned avian expert, led the release, called hacking, of the captive-bred birds in Virgina. And he counted on his students to be the boots on the ground.

Thanks to their efforts, the first successful peregrine breeding pair in Virginia was recorded on Assateague Island in 1982. In 1999, the peregrine falcon was removed from the U.S. Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.

Their work is still making an impact today and the university’s new students and faculty are carrying it forward, strengthened by the close faculty mentorships that are a hallmark of a William & Mary education.

W&M’s work in conservation spans disciplines, expertise and departments. From the Center for Conservation Biology to the Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences & VIMS to the Institute for Integrative Conservation and beyond, the university community is driving transformative research to ensure the well-being of the planet. Through the Year of the Environment W&M celebrates its commitment to safeguarding the environment and the communities that depend on it.

A group effort

By the 1960s, the widespread use of DDT had spurred a precipitous decline in the populations of several raptors, including peregrine falcons. Interfering with calcium metabolism, DDT weakened eggshells, resulting in a loss of young.

While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency banned the use of DDT in 1972, the damage had already been done. Bringing the birds back to the eastern U.S. required the establishment of a special taskforce, including Cornell University, William & Mary and several government agencies.

Cornell, which created The Peregrine Fund, was tasked with deciphering how to breed peregrines and hatch chicks in captivity. A team at William & Mary, led by Byrd, managed the hacking.

“Hacking was developed centuries ago by falconers as a means of building flight skills and strength prior to actual training,” said Bryan Watts M.A. ’87, W&M research professor and director of the Center for Conservation Biology (CCB). “That practice has been successfully adapted by conservationists to reintroduce captive-reared birds into the wild.”

Dana Bradshaw ’81, M.A. ’90 remembers the process well. As an undergraduate, he was stationed in Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge during the reintroduction project’s first phase on the outer coastal plain.

“The fledgling peregrines would arrive at the site around 15 to 30 days old when they were still incapable of flight,” he said. “After they were transferred to a hack box, we would feed them blindly through a chute at the back of the box to minimize human interaction.”

Feedings continued for several weeks as the birds imprinted on their location, which they could see through the front of the box, and exchanged fluffy down for feathers capable of flight. When they were around 45 days old, the cage was opened and they had their first chance at freedom. What followed was a fascinating and sometimes comedic scene of trial and error.

“They’d start to make their first flights, tentative and short at first and then longer and farther as they gained confidence,” said Bradshaw. “Typically, the males flew first as they tended to be smaller and more angsty than the females, hopping up and down in the cage, ready to go.”

The hack site attendants’ job was then to monitor and continue feeding the young birds until they demonstrated proficiency flying, landing and hunting. They didn’t master all at once.

“Sometimes they’d fly gracefully down to the ground but end up in a heap of feathers because they’d overshot the landing,” said Bradshaw.

When the young birds started to come back with full crops, Bradshaw knew they were finding food and well on their way to independence.

The fledgling phase is one of the most vulnerable for maturing birds, which Bradshaw saw firsthand. During his summer on Chincoteague, he and his partner discovered that an adult male peregrine had already set up camp on the island. Fiercely territorial, he hounded several young falcons, chasing them out over the ocean.

“They’d eventually lose energy and crash into the waves,” said Bradshaw. “It was a real tragedy because each bird was essential to the recovery of the species.”

Despite the challenges, the coastal recovery program released 115 young peregrines between 1978 and 1985 in Virginia. Over 85% of the birds were reported to have successfully matured and dispersed.

After proving the technique worked on the coast, Byrd and his students took the program inland to the peregrines’ historic mountain eyries. Here, Amanda Allen Beheler ’92, M.A. ’95 spent three months over three summers hacking peregrines on Hawksbill Mountain in Shenandoah National Park.

Working near one of the park’s most popular hikes, the somewhat reserved Beheler got to practice her communication skills, educating hikers, reporters, scientists and other curious individuals about the project.

“Despite being in the middle of the woods, we had semi-celebrity status,” said Beheler. “Everyone loved the peregrines, and people would come from all over to watch them. To this day, I still have friends whom I met during those formative years hacking.”

W&M students like Beheler and Bradshaw continued hacking until 1993, when the program was discontinued. Over 130 birds were released in western Virginia across nine hack sites. The birds had a 90% success rate.

Gradually, the population of peregrine falcons in Virginia started to grow. In 2024, there were nearly 35 breeding pairs on record.

Through the CCB, which he co-founded with Byrd in 1991, Watts continues to support peregrine conservation efforts in Virginia. Working with W&M students, he bands the birds, monitors their numbers and maintains nesting sites.

The William & Mary way

For Beheler, Bradshaw and other students who worked on the peregrine project, Byrd was a lifechanging mentor.

“He was one of the first people who trusted me with something important,” said Beheler. “He and Bryan Watts, whom I worked with during my master’s degree, are both brilliant and amazing mentors. And they’re very humble. You can’t get much better than that.”

Beheler’s experience is emblematic of the close faculty/student relationships that give William & Mary its reputation as a standout for undergraduate education.

Learn more about peregrine falcons and their conservation on the CCB’s website.