A Launch Into Stem Futures

Camp Launch Ignited Opportunities for Gifted Middle-School Students

October 1, 2016

By

Ashley K. Speed

The small robot swivels, then zooms past the upside-down plastic cup before stalling. Reset. This time, it winds itself around the same plastic cup, then another, but stops short of the final one. The staggered three-cup maze is more daunting to overcome than it appears. Reset. More speed is needed. This time the robot’s motor hums as it goes by – zipping in between all three cups on the final trial, making it to the finish line.All the while, the LEGO robot is controlled by a 12-year-old girl sitting at a computer.

The class, LEGO robotics, is one of several that 65 students at Camp Launch completed in July. The two-week residential camp is operated by the Center for Gifted Education at William & Mary’s School of Education at no cost to students’ families.

The camp, started in 2012, immerses high-ability seventh- and eighth-graders in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) curriculum, writing and personal development coursework. Students live as college students; they stay in dorms, take classes in various buildings on campus and eat in dining halls.

Campers selected must live within a 75-mile radius of Williamsburg — a vast area that covers thousands of academically gifted children of modest means from rural and urban areas who, despite their intellect, may not be privy to the educational opportunities of their peers.

“Inspiring talented middle-school students to see the possibilities in STEM careers and more importantly, to see themselves working in STEM careers provides greater academic engagement to increase the probability for current and future academic success,” says School of Education Dean Spencer G. Niles. “As students consider career possibilities, it is critical that they are exposed to others who look like they do and come from similar backgrounds. When a supportive and encouraging environment is provided, then the possibilities become more realistic and personal than when such opportunities do not exist. Camp Launch serves these purposes.”

ROBOT WARS: In Camp Launch’s LEGO Robotics class, students must program and maneuver a robot through a three-cup maze, making tweaks along the way to the finish line.

Inside the Classroom

A tanker truck moves swiftly down Jamestown Road. Too swiftly. It overturns, spilling hydrochloric acid onto the roadway and into College Creek across from Lake Matoaka.

What affect will this acid have on wildlife in the creek? What is the pH of the spilled acid? How can the fluid be neutralized?

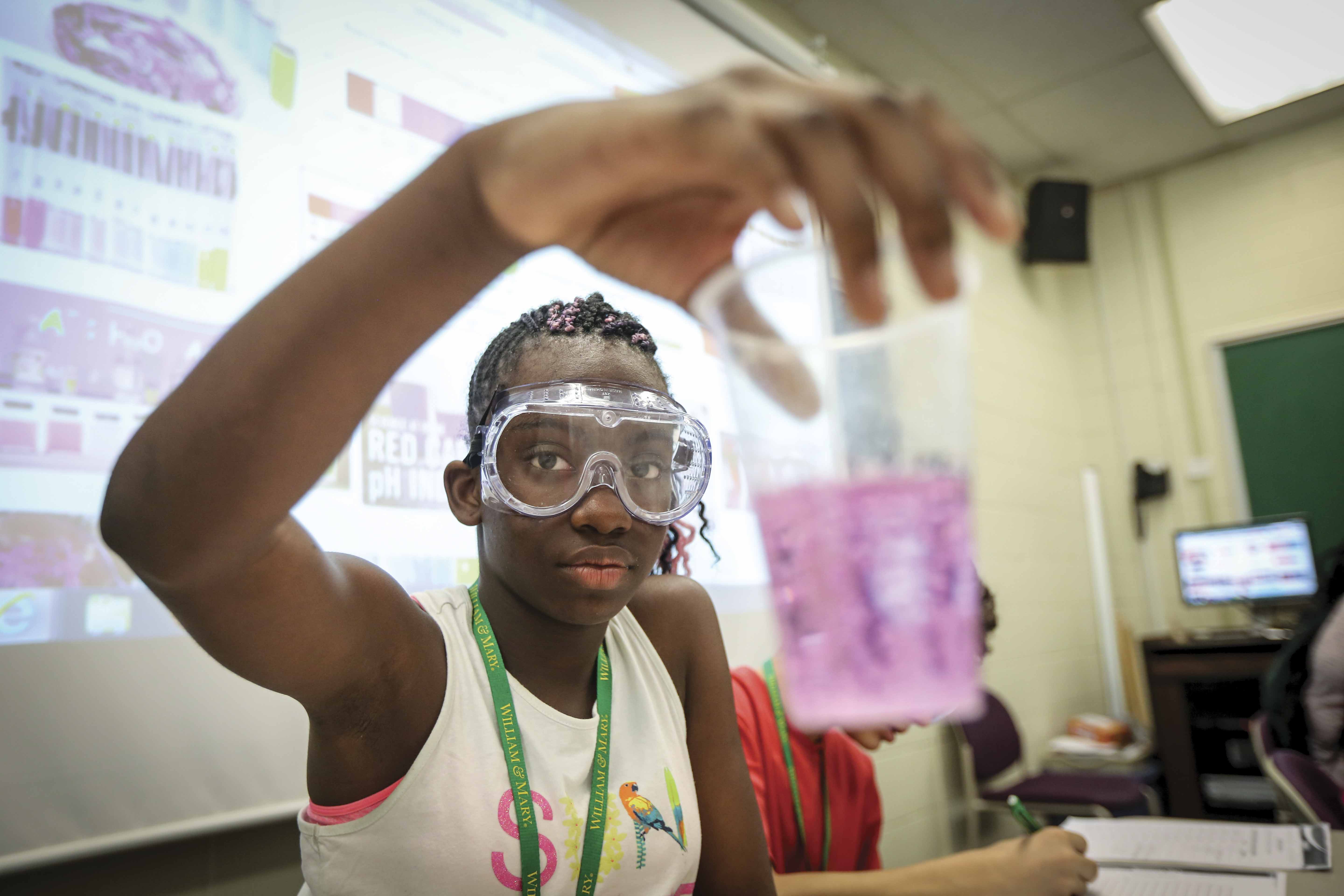

This is the scenario Camp Launch students are given to analyze and the questions they must answer in the Acid, Acid, Everywhere class.

“We learned how to measure the pH of something and make it a base,” says 12-year-old Ja’Ryiah Barnes, who wants to be a forensic scientist. “I did it once before, but I didn’t get it. When I came to Camp Launch and I learned it here, it was really fun. This program gives us opportunities to do different things and gives us a chance to figure out what we want to do later on in life.”

Interdisciplinary learning was weaved throughout the curriculum. This particular class assignment blended chemistry with journalism.

Barnes and other students took a field trip to College Creek where the imaginary acid spill occurred and conducted water quality tests to determine the creek’s health. Their final assignment was to write a newspaper article about the accident and explain how to remedy the acid spill.

Camp Launch teachers use creative twists like this on traditional subjects to help students learn and to keep them engaged. Writing teacher Angela Bartle used food to strengthen students’ ability to describe things when one of their senses is absent. While blindfolded, students ate grapes, marshmallows, celery, cookies and chocolate.

Some campers were stumped by the assignment.

One student said she loves chocolate chip cookies, but had no idea what she was eating with the blindfold blocking her eyes. Campers also learned different forms of poetry, figurative language and imagery in Bartle’s class.

When the blindfolds came off, the mystery foods were revealed and the students could once again see their gifted counterparts — counterparts who they became fast friends with as they maneuvered science, math and writing classes on a college campus miles away from home.

“Being with likeminded students helps them to have no fear of being intelligent, gifted and different, because all these kids are really unique,” Bartle says. “They all accept each others’ differences because they realize, ‘hey, I’m different too.’”

The Gifted Student

Tracy L. Cross, executive director of the Center for Gifted Education, grew up with an awareness that being different can come at a cost. Being different for Cross meant being among three siblings all labeled academically gifted. It was a title that caused his mother to shudder because she just wanted her kids to be “normal,” and yearned to shield them from the judgment that can come with societal labels.

The title “gifted” means evidence of extraordinary ability for future accomplishment. Nationally, 6 to 10 percent of the total student population is comprised of gifted children, according to the National Association for Gifted Children. This percentage only accounts for students who are formally identified as such.

In a September 2015 article for the Journal for the Education of the Gifted, Cross, Laurence J. Coleman and Karen J. Micko examined the dynamics of being a gifted student in school.

“Accounts of children expressing a sense of differentness are so common among persons who work with gifted children that the sentiment is often taken for granted … Feeling different is not unique to gifted children, but in their case, they actually are different. Children who are gifted differ from chronological peers in two fundamental ways: ability and motivation,” the authors wrote.

Difference in ability for a gifted child reveals itself in the faster pace at which they learn, being more engaged in a particular interest and being able to understand more deeply than their peers, according to the authors. Motivation for gifted students is considered more of a trait — an inescapable force that goes beyond passion or interest.

“This is really a special population of kids,” says Morgan McNally M.Ed. ’14, a fourth-year camp counselor. “They are very inquisitive. Their critical thinking skills are so impressive. They enjoy problem solving, they enjoy being challenged and when they get around students like them, they feel safe. They feel like they can be who they want to be at camp. Some said they wish school was like camp because there are people here who understand them.”

While the school and home environments of some gifted children foster educational excellence, other gifted students’ academic skills are shunned by peers or stigmatized by society. Camp Launch was designed to enhance and support campers’ intellect. The program started in 2012 and is run by Mihyeon Kim, director of pre-collegiate programs at the Center for Gifted Education.

“We are trying to build something called the scholar-self,” Cross says. “It’s the ideal that each student would carry with them: the idea that they are a scholar. We’re not trying to convert people to be academics but instead promote the idea that I can do what I want to do because I have the capacity to do it. But they need to have the agency to do it and they need to have some key information that they’re not going to get unless something like Camp Launch intervenes.”

Cross wants the impact of the camp to go beyond the two weeks students spend on campus. He’s trying to find funding that will put technology in the hands of the students when they go back home via an iPad or a Chromebook — tools that would allow them to use Wi-Fi at a local library for homework, to look up colleges and to stay connected to Camp Launch staff. If the additional funding for technology is secured, Cross will assign someone to share information with the students throughout the year about various educational resources.

“Leveling the playing field is part of what we are trying to do,” Cross says. “Some of our kids don’t have access to technology. It would allow them to compete more favorably with other students in school.”

BENEFACTORS: Mike Petters M.B.A. ’93 and Nancy Briggs Petters ’81 recently provided a $1 million gift to Camp Launch to support the program going into the future.

The Gift

A recent $1 million gift from alumni Nancy Briggs Petters ’81 and Mike Petters M.B.A. ’93 to fund the camp was given as a way to support Camp Launch, but also to level the playing field that Cross speaks of.

“In education, we talk a lot about the intersection of poverty and education as being a Gordian knot of a problem,” Mike Petters says. “For us to be able to try to start to untie that knot for some people could have a tremendous impact and is something we’re just excited about being able to do.”

The Petters’ gift comes at a critical time for Camp Launch. The camp initially received startup funding and three additional years of support from a private foundation, but its future was uncertain before the Petters stepped in to help.

Supporting education is a priority for the Petters. Nancy Petters is a preschool teacher who comes from a long line of educators. Both of their daughters followed in her footsteps and became teachers as well.

“If we can help someone experience a program they otherwise wouldn’t experience, they might be able to make some changes and some decisions that could impact their own future and that of their family,” Nancy Petters says.

Mike Petters, raised by a hardworking family on an orange farm in Florida, was the first in his immediate family to go to college. But the thought of even attending college seemed out of the realm of possibility in the rural community where he was reared. Things changed for him when he received a scholarship to attend a Jesuit high school and later another scholarship to attend the United States Naval Academy.

“On the first day I went to the Jesuit high school, the question in my life changed from ‘are you going to college’ to ‘where are you going to go to college,’” says Petters, who credits those scholarships with changing the course of his life.

It was a path that eventually led him to his current role as president and CEO of Huntington Ingalls Industries in Newport News, Va. — which, for decades, has funded college tuition for its employees. Earlier this year, Mike Petters donated his salary to support early childhood education and college tuition for shipyard workers’ children.

SOLUTIONS: All-inclusive education campers engaged in STEM cures in addition to courses in writing and personal development. Within a supportive and encouraging environment, campers are surrounded by other students who comes from similar backgrounds and who are motivated to learn new things.

A Child’s Lens

“When you combine two or more simple machines, what do you get?” Camp Launch engineering teacher Jeff Fry M.Ed. ’13 asks his class inside Tucker Hall.

“A compound machine,” the students say in unison.

During the camp, students in Fry’s engineering class learned about simple machines, strong geometric shapes, bridge designs, crash barriers and the importance of teamwork in engineering.

This was Fry’s fourth summer teaching at Camp Launch.

“I became involved with Camp Launch in order to teach students that engineering is a fun career choice that will allow them to pursue many different parts of the world that we live in,” Fry says. “During our class we discuss everything from aeronautic engineers to civil engineers to forensic engineers to chemical engineers.”

On a recent summer afternoon, Fry was using a real-life example to teach students why the structure of an item is important to its function. His main visual aid: a can of soda. Fry explained to students why the can was designed with a concave bottom instead of a convex one. Fry accompanied his lecture with a slide that showed the changing design of Coca-Cola and Pepsi cans dating back to the late 1940s.

“If it didn’t have a curve and was flat at the bottom, it wouldn’t support carbonation,” Fry says. “It would explode.”

“How would that make a difference?” a student asked.

“The can wouldn’t hold the carbonation,” Fry says. “You wouldn’t be able to fill it.”

Smarts are Cool

Camp Launch students are very direct about what they enjoy about camp. Most don’t hesitate when answering. For some it’s a particular class or the discovery of an exciting future career. Others speak of the temporary, yet exciting independence gained through being away from home for two weeks, the excitement of operating a LEGO robot with the stroke of a keyboard or the wonder that comes with making a new friend.

“I enjoyed the college experience of being on campus because I want to go to college,” says 12-year-old Isaiah Motley, who wants to be an engineer or a zoologist. “Being here is teaching me how to deal with people in a new setting. We’ve only been here for two weeks, but 99 percent of the people are really close friends, which I didn’t think was going to happen.”

One of the most valuable lessons mentioned by campers: Being smart is nothing to be ashamed of.

“My favorite class is personal development,” says 12-year-old Franciyana Freeman, who wants to be an OB-GYN. “It makes me feel like I don’t have to be scared to be who I am.”