It was 1918. World War I was coming to an end, streets were crowded with Model T cars, movies with sound didn’t exist and the Spanish flu was rampant across the U.S. It was also the year a U.S. president for the first time declared his support for women’s suffrage. A century ago, everything was different.

One Hundred Years

When women came to the university, Mary didn’t just join William, she saved William.

September 17, 2018

By

Noah Robertson '19

with contributions by Mattie Clear '18

Photography By

Eric Lusher

For 225 years, William & Mary, a small liberal arts college nestled in Williamsburg, Virginia, only educated men. But that was about to change.

In 1918 William & Mary faced an almost insurmountable challenge. Students had abandoned their books for the battlefield and total enrollment was less than 150 students. The university was deep in debt, and there were only two options: change or shut down.

William & Mary President Lyon G. Tyler, a longtime advocate for women’s education, decided it was time to change. He partnered with women’s rights activist Mary-Cooke Branch Munford, and together they fought for women’s admission to the university. In February 1918, the Virginia General Assembly authorized William & Mary to admit women students for the fall semester.

When women came to the university, Mary didn’t just join William, she saved William.

In 1918, 24 women arrived for their freshman year.

It was the birth of a new era, at William & Mary and in the world. That year, a new generation of students walked through the Wren Building.

The women were — intentionally — housed on the edges of campus. All but one from Virginia, they were used to the long skirts and strict rules expected of Southern women.

They weren’t allowed to wear pants or stay out at night.

But neither the resistance from male students nor the challenge of being first slowed them down. When they weren’t allowed to participate in existing sports or student government, they organized their own.

In less than 15 years, there were more women students than men.

Today, women make up 45 percent of university faculty and 58 percent of the student body. A woman, for the first time ever, also now presides over the Alma Mater of the Nation.

Progress has been possible because of the tireless work of William & Mary women over the last 100 years, including the first African-American residential students who arrived on campus in 1967.

And in those 100 years, every woman at the university has left her mark on that progress.

A century of women at William & Mary has left innumerable artifacts — pieces of their own history reflecting decades of change. Hidden in each of them is another question: what is to come?

The doldrum days are over and change is happening every day. So let us ask:

What will Mary change tomorrow? What artifacts will be created in the century to come?

Early Experience

Many of the first women students at William & Mary didn’t think they were groundbreakers, although most women following in their footsteps think otherwise. In the early part of the 20th century, when life expectancy for women was 42 years and there was no minimum wage, the world was changing around them. Looking back, coeducation was important, but in 1918, most of the attention was on World War I.

In the first years of coeducation at William & Mary, rules were strict.

Women students had to be in their dorm right after dinner and either in their room or the library between 8 and 10 p.m. If they wanted to leave campus, they needed a permission slip. They couldn’t ride in someone else’s car unless they had an approved adult driver.

Campus life, though, was more than just rules. In 1918, women students had an after-dinner social hour in their dorm until 8 p.m. Every night, they rolled up the carpets in the lounge and danced to music played from one of their hallmates on a piano. They formed their own student government and sports teams, and while some early women students said their experience was hard, others remembered their time at William & Mary as the best in their lives.

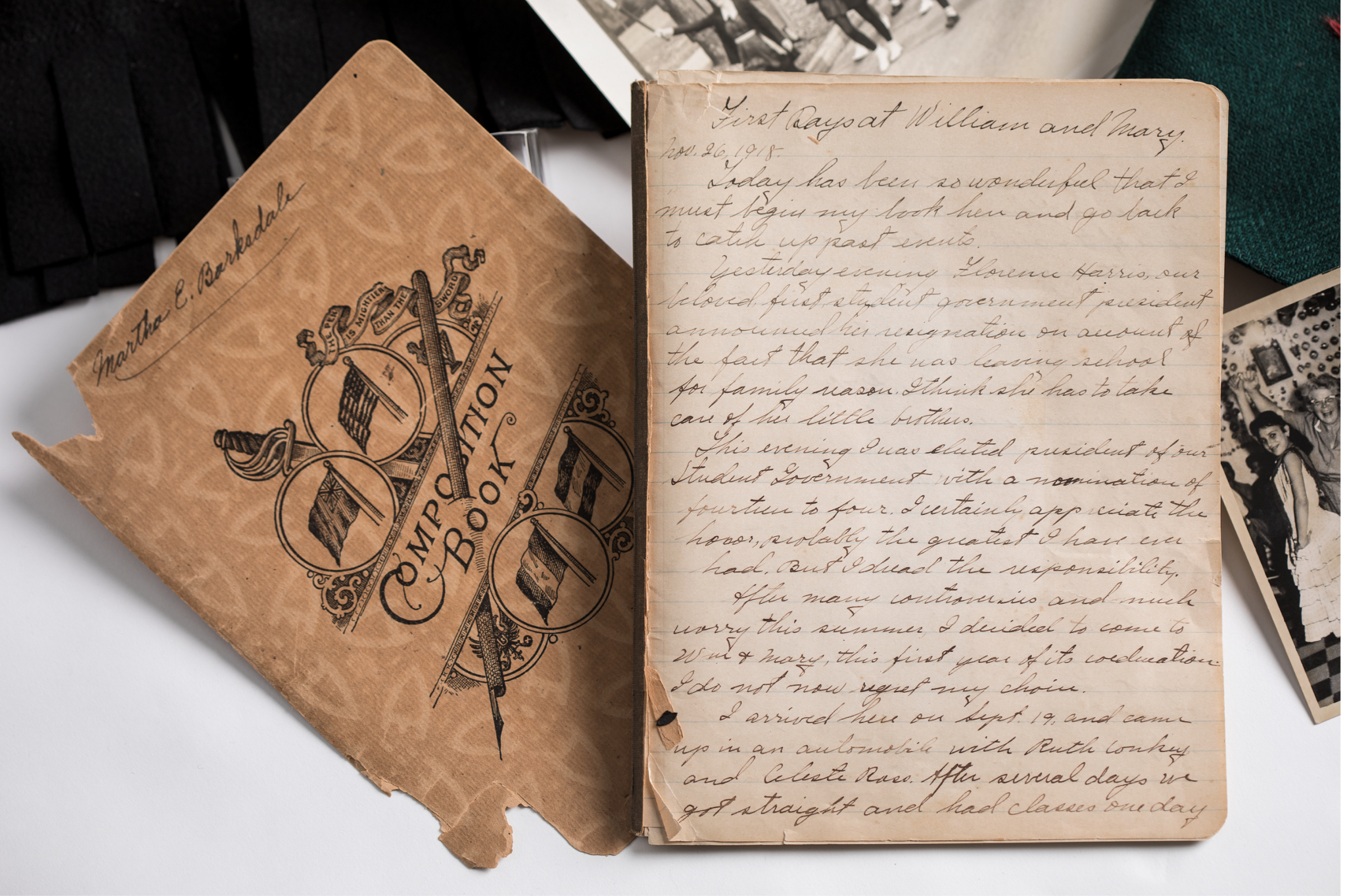

The early experience of women at the university, so different from that of today, is recorded in normal pieces of everyday life. A handmade pillowcase recalls the university’s early colors of orange and black. Scrapbooks and diaries record historic events, like a visit from U.S. President Warren G. Harding LL.D. ’21 in the early 1920s. Harding attended William & Mary President J.A.C. Chandler’s inauguration and received an honorary degree.

A monogrammed blazer reminds us how students used to dress, and debonair dance cards recall their social lives. Some of their stories survive in university records and oral histories. Some of the first women, like Martha Barksdale ’21, have places on campus named after them today.

Even if their artifacts didn’t survive, even if their journals and photographs have been lost with the passage of time, their legacy remains. Those women were the firsts, and even if they didn’t realize it, they were groundbreakers.

From the Archives

Explore images representing 100 years of coeducation from Swem's Special Collections Research Center

ViewWomen's Social Groups

College gives you some of the best memories of your life. Often, you’re on your own for the first time, learning new things, with your whole life ahead of you. With every class or hour in the library, you’re stepping into your own future. It’s full of stories you’ll tell for decades to come.

The best part of these memories, though, is the chance to share them. It’s often not the things you do but those you do them with. To be surrounded by people of similar ages and interests can be a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

The way women spend time together at William & Mary has changed over the years, but there has always been a constant focus on building relationships. The ribbon societies, formed in the first years of coeducation, were like an early form of sororities. Women wore green or yellow ribbons on their wrists or ankles, and staged events around Homecoming and organized yearly dances. They were groups of women who enjoyed spending time together.

Women’s social groups at the university have traditions and histories of their own. They might come in the form of invitations to events or group advertisements, like a Delta Sigma Theta poster that proudly reads, “Welcome into our queendom.” It could also be something small, like a customized William & Mary compact.

Over the last 100 years, William & Mary women have formed bonds that lasted much longer than their time at the university. With leftover scrapbooks or photographs, we can look back at those relationships. Whether they’re in black and white with a ribbon society in the 1930s or in full color with their sorority sisters in the 1980s, they’re standing together, arm in arm, smiling.

Aviation

William & Mary is believed to be the first university with a flight club. From 1931 to 1935, members could join for a yearly fee of one dollar, and in its five years 44 students completed the necessary 20 hours of flight time to earn their private pilot’s licenses. Only one of those 44 was a woman: Minnie Cole Savage ’33 — the first, and last, woman to earn her pilot’s license through William & Mary.

Savage finished her training in a thick corduroy flight suit, lined with a felt interior, obviously cut for a man. Just like the other members, she wore the silver and green flight club patch, and she flew in the nighttime aerial stunts and the yearly Homecoming exhibition. Three times a week, in her baggy overalls, she went to the College airport and worked on one of the four planes with a William & Mary crest. Her name is engraved in a trophy commemorating the flight club and their 1933 victory in the Loening Cup — the highest award for a college aviation program.

A black-and-white photograph shows Savage sitting close to Amelia Earhart during her visit to William & Mary. Earlier in the night, Earhart spoke on the importance of women in aviation, who showed great “zeal and vigor” by participating in a sport then considered a near-daredevil activity. From Earhart, outstanding “zeal and vigor” was only one seat down.

Savage pushed boundaries as a student, an aviator and a woman. The same woman photographed in the Colonial Echo with a coy half smile, wearing a dark sweater and floral scarf, was an enormous groundbreaker. Savage set an example for women at William & Mary — accomplish your goals even if you’re the first; fly to your castle in the clouds.

World War II

Margetta Hirsch Doyle ’45 was a regular student at William & Mary. Her friends called her “Getta” and she was a Kappa Delta. Doyle kept a diary and wrote about her philosophy quizzes, described how much she enjoyed making Red Cross surgical wrappings and mentioned hours spent spotting airplanes from campus buildings.

Doyle was a student during World War II.

During the second World War, William & Mary became a predominantly female campus. While many college-age males fought abroad, women kept up the war effort from Williamsburg. In between their studies and social life, students volunteered with the Student War Council and the American Red Cross. Along with other service work, they, like Doyle, made surgical dressings and spotted airplanes, sometimes in groups and sometimes alone.

Near the war’s end, as the U.S. continued to construct military equipment, William & Mary requested that one of the newly made sea vessels be named after the university. Part of a new class of U.S. “Victory Ships,” and one of the first on the East Coast, the SS William and Mary launched in Baltimore, Maryland, on April 20, 1945. President of the Women Students’ Cooperative Government Association Eleanor Harvey Rennie ’45 christened the ship earlier in the day with a champagne bottle wrapped in a red, white and blue cloth.

Unlike most of the women students during that time, Harvey received recognition — in the form of a bouquet and jewel-encrusted pin at the christening. But as a group, women sacrificed their time, energy and spirit to support a war thousands of miles away. It was a time of empowerment, when women’s wartime work was trusted and needed.

The university still has the American flag from the SS William and Mary. Many of its stripes are torn and frayed at the end, but all the stars are intact.

100 Years Installation

Explore Images of the unique installation at the Sadler Center celebrating 100 years of coeducation at William & Mary

ViewTradition

For decades, incoming freshmen at William & Mary wore duc caps — beanie-like hats — throughout their first year at William & Mary. A new tradition, Duc (short for introductory) week, was filled with unusual and sometimes arbitrary rules set by upperclassmen for the new students. Anytime they were in Williamsburg or on campus, they had to wear their caps — so the duc rules commanded.

William & Mary is full of traditions, some lasting and some lost with the passage of time. Adopting a community’s traditions is an important part of fitting in. Decades ago, new students did as they were told and addressed upperclassmen as “sir” or “ma’am,” because in two years, they would be upperclassmen themselves. Duc week wasn’t just a way for older students to feel self-important, it was a way to build community among the freshmen, with special events throughout the week.

At the same time, for many it’s important not to fit in too much, and the old “W&M Women” handbooks are a good reminder. For decades, women students used to receive these books during orientation in addition to the normal student handbook. They were full of social rules for women, who had to sign in and out of their dorms when leaving campus and couldn’t enter fraternity houses alone. An 11 p.m. curfew wasn’t lifted until 1971.

William & Mary is full of history, more than 325 years of it. History leads to tradition and tradition to community, but the healthiest communities aren’t restrictive. They encourage individual and group identities; they conform and express at the same time.

The university, of course, no longer gives women students their own handbook. After a century of coeducation, they have maintained the university’s traditions and added new ones along the way — all with the same reminder: there is no single “William & Mary Woman.”

Athletics

When women’s athletics began at William & Mary for the first time in 1918, there were clear boundaries. Women weren’t allowed to compete with the already-existing men’s teams; they had to start their own.

So they did.

Within months, women students arranged an intercollegiate basketball game against the University of Richmond — the first of its kind at William & Mary. In 1923, the women’s basketball team celebrated a perfect season. After their victory over archrival Westhampton, a 1923 Colonial Echo article read that “pandemonium broke loose.”

Women’s sports were different back then. The women wore long and baggy bloomers with black leggings tucked into hightop shoes and rolled-up cotton T-shirts. Lest males see them in gym clothes, they had to change right after exercising. During the perfect five-game season in 1923, the basketball team only scored 166 points. The team’s names, positions, opponents and game scores were all written on a single stick, celebrating the season.

By the 1950s, women’s bloomers were gone in favor of green skirts. Gym classes still required a university-wide uniform, and the official cotton T-shirt was available for order at the bookstore.

Today, the uniforms are gone, and the university has 11 varsity women’s athletics programs, more than 200 women all-American athletes and countless conference championships. The coach of the United States women’s national soccer team, Jill Ellis ’88, L.H.D. ’16, is a William & Mary graduate.

William & Mary women excel, in the classroom and on the field. They went from having no athletics programs at all to finding remarkable success on a national scale, and there’s no end in sight.

Social Change & Activism

Change does not happen in a vacuum. It takes time, effort and activism. It’s a call to action; it adds purpose to the passage of time. Change relies on a special kind of person, willing to work with others for a common cause or be the lone voice in a silent crowd.

Over the last 100 years, William & Mary women have been changemakers. The difference in life on campus in 1918 and 2018 testifies to that. A century ago, women students were allowed on campus for the first time. Now, a woman is the university president.

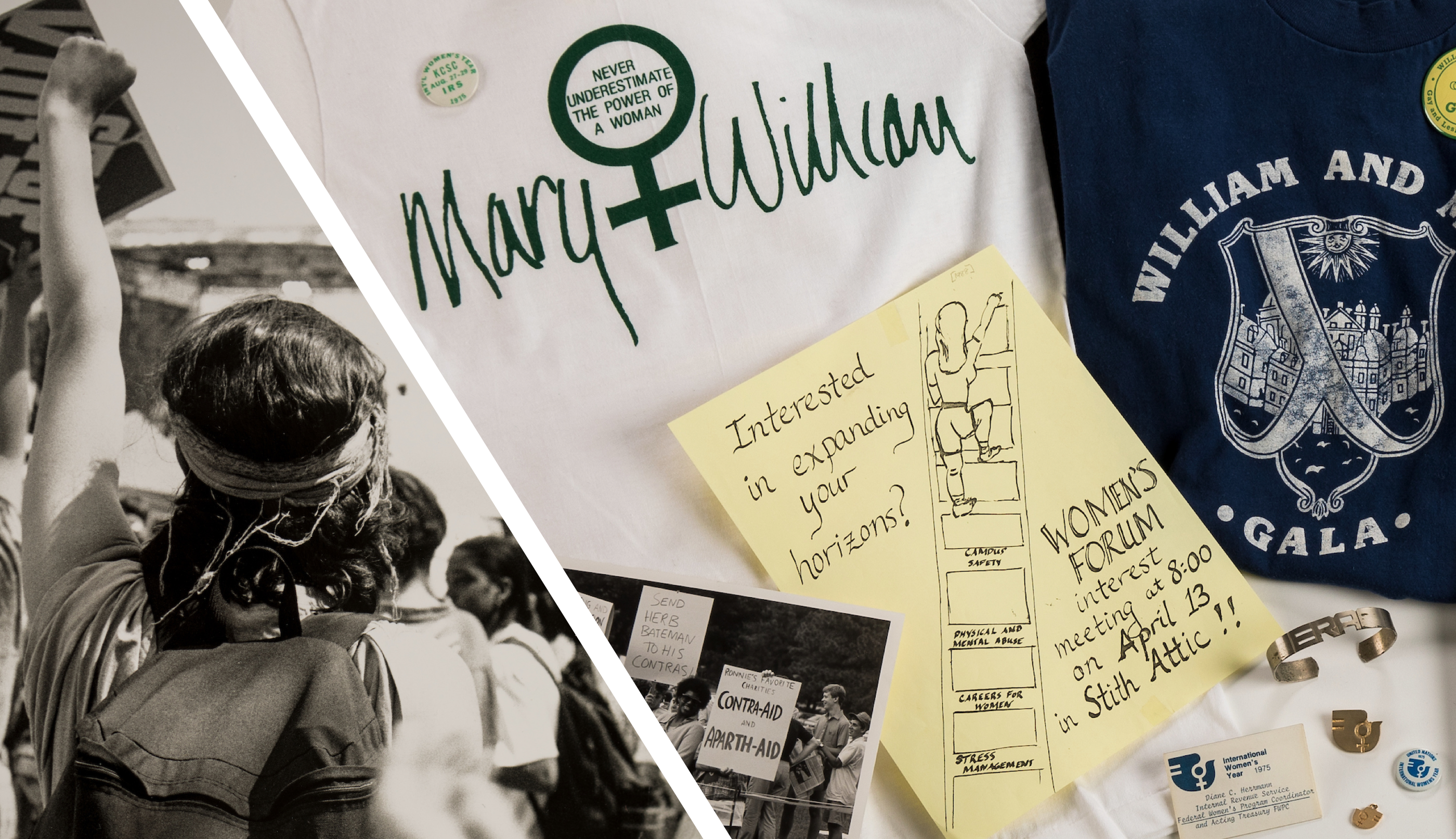

All this change required actions both big and small. It demanded protests, filled with banners and handmade flyers for small groups, discussing what it was like to be a woman on campus. It took the momentum of nationwide movements, which came with T-shirts, buttons, bracelets and pins. And it also took bold declarations, like Flat Hat editor Marilyn Kaemmerle’s ’45 editorial calling for racial integration, which gained national news and almost got her expelled from the university. Sometimes the movement fails, sometimes it succeeds and sometimes both are necessary to move forward.

William & Mary is not the same as it was 100 years ago; it’s better. That progress is a cause for celebration, but also motivation. Change is for the discontented, including for those who demand a better future. It’s time to honor those changemakers and also learn from them.

An old university T-shirt says it well: “Never underestimate the power of a woman.”

Let this be a reminder: Never underestimate the power of a William & Mary woman.

Handmade

In the first year of coeducation, William & Mary had no history of women students: Mary was with William for the first time. From 1918 on, everything those first students did was an act of creation. Women students made their own history, and they made it by hand.

But while history is made, it’s not always made on purpose. In the first few years after 1918, university professors often referred to their students as “pioneers,” a name they quickly grew tired of. Most of the newly admitted women weren’t there to make a statement. They just wanted an education.

After a century, the challenge of recording history continues with the history itself. It’s always visible in the big moments, like the university’s 300-year anniversary — for which an alumna spent five years creating an enormous quilt stitched with images of academic buildings and famous graduates. The university’s coat of arms shines in its green, gold and silver, right on front.

History also shows in artifacts such as handmade books that took a semester to make, a Mary and William T-shirt or golden heels with the coat of arms worn proudly at graduation. It’s in unexplained sorority paddles and signs, self-published magazines with entries from women students all over campus. And it’s in a handmade graduation cap, decorated with a custom library card and encyclopedia-paper rose petals. Mattie Clear ’18, a four-year employee at Swem Library’s Special Collections Research Center, made it for her graduation.

Sitting in a library room, surrounded by artifacts, Clear looks around. Hundreds of objects, some a century old lie around her — everything from scrapbooks to shoes. All came from women at William & Mary, and some way or another, all made it back to their alma mater. She pauses and looks up again.

“I’ve sort of been learning about myself through the eyes of these people for so long,” Clear said. “You know, it’s strange telling your own story.”