When Virginia “Ginny” Claudon Allen ’40 climbed aboard the plane headed to her first Red Cross assignment overseas, she was convinced she was going to France. Instead, she ended up in Calcutta.

“They didn’t tell us where we were going, but I had majored in French in college and spoke it fluently, so I just knew we were going to France,” she remembers. “When we took off, I told my friend we would soon see the Statue of Liberty. I took a nap, woke up and when I looked out the window, we were going the wrong way and all we saw were cornfields. Pretty soon we were on a ship headed across the Pacific Ocean.”

It was only the first of many surprising experiences Allen experienced as a Red Cross worker stationed in the Pacific theatre during World War II. Serving from 1944 until 1946, Allen did it all: she worked with off-duty G.I.s, served as a G.I. Jill radio personality for troops in the China, Burma and India theatre and performed in plays all over India for the benefit of homesick G.I.s.

There was nothing in Allen’s background that foretold this kind of adventure. Describing her youth, she tells of an upper middle class existence as the daughter of a large Illinois landowner and his homemaker wife. She speaks of a childhood where the family, which included brother Chet Claudon ’43, evaded the cold Illinois winters by escaping to Florida, where they would swim in the ocean and play on the beach. Even the Great Depression didn’t interfere with the fun — the family stopped buying extras and sought out more free activities, but Allen said they escaped relatively unscathed.

When it came time to consider college, Allen was initially swayed by a group of friends to try Georgia Wesleyan College. But Allen didn’t care too much for the rules at the all-female institution. For example, they would hold dances and invite men from neighboring schools, but the women were forbidden from dancing with the men. She remembers talking, drinking punch and gazing longingly at the empty dance floor as the orchestra played all their favorite songs.

Her mother’s family was from Virginia and Allen had grown up hearing the stories about the bucolic countryside and the charm of Colonial Williamsburg. William & Mary had its own set of policies for female students — they had a curfew, after which they were locked in their dorms, had a separate student government and women were not allowed to smoke outside when on campus. However, they were not as restrictive as Georgia Wesleyan, so she thought it would be a better fit.

“In those days, it was difficult for an out-of-state student to get admitted. I’m convinced that I was accepted because of my essay — I wrote from my heart,” she says. “I wrote about my family’s long history in Virginia and how I longed to be part of my heritage, and I think that sincerity came through.”

Having been initially waitlisted at William & Mary, her application was finally accepted and she arrived in Williamsburg, where she proceeded to enjoy what she considers an idyllic college experience.

“I had heard about Williamsburg for a long time, and I thought it would be charming,” she says. “It sounded like Shangri-La.”

Indeed, one of her most treasured memories of her time at William & Mary was the time she met film legend Cary Grant, who was in Williamsburg shooting the 1940 film “The Howards of Virginia.” Allen had just undergone an appendectomy when her boyfriend at the time, working as Grant’s stunt double on the film, brought the movie star to visit her hospital bed.

“He was lovely, but unshaven — I think my boyfriend had just gotten him out of bed to come visit,” she says. “He told me that my boyfriend really loved me and I told him point blank that we were just too young for anything serious!”

Allen’s brief interlude with Grant was cut short when the nurses connived to get him out of the room by claiming that a new mother in the maternity ward had just named her new baby “Cary.”

“I don’t even know if there was a baby, or if it had any notion of being called Cary,” she says wryly. “ But for the longest time, I kept one of Cary Grant’s cigarette butts as a souvenir — along with my appendix!”

Allen majored in French and English, and her plan was to go to France and teach English — one of the few occupations open to women at that time. Although two of her classmates went on to become lawyers, the expectation was that most female graduates would go on to marry and become mothers and homemakers shortly after college.

For her part, Allen went with her family to Palm Beach, Fla., working in an accountant’s office as a receptionist, making $15 a week, before transferring to Ream General Veterans Hospital, located in The Breakers. At the time, it was one of the town’s most ritzy hotels. Her title was to be a secretary and stenographer but with World War II now raging at home as well as abroad, her real job was to socialize with the wounded flyers coming home from Europe, some of whom had suffered unspeakable injuries.

“I learned to become comfortable with people in absolutely terrible conditions — recovering from really destructive injuries — and to treat them normally,” she remembers. “It was really terrible and difficult at first, but I got better at it, and they appreciated it.”

In the summer, the hotel closed due to the fact that it had no air conditioning and the humid summer air was deemed less than ideal for the recovering veterans. The veterans were sent north and Allen then transferred to the Morrison Field Army Air Base in West Palm Beach, Fla., where she got a job in the intelligence office.

After her steady boyfriend was killed in action, Allen knew she had to do more to help the war effort. Hearing that a friend had joined the Red Cross and had been stationed in France, Allen decided to follow in her footsteps.

“I just knew I was going to France to drive an ambulance,” she recalls. “So, of course — I didn’t!”

Allen, along with her friend, Jane, landed in India, where she stopped in Calcutta on the way to Karachi. Although Allen, Jane and the rest of their fellow female Red Cross employees had just recently been forbidden from attending a Bob Hope U.S.O. show on the grounds that Hope’s jokes were deemed too off-color for women, there was no one to protect their delicate eyes from the horrors of Calcutta.

“It was appallingly dirty and there was refuse in the water,” she recalled. “People were lining the streets begging, and many had been infected by

elephantiasis, a swelling disease caused by parasitic worms. Not to mention all the children who had been deliberately blinded so they could become beggars. Everything was covered with swarms of flies.”

While on the boat headed to India, Allen had been tapped to take a turn as an announcer for the ship’s radio station. Once Allen arrived at her destination, Agra, she learned that her turn at the microphone had not been mere chance; she had actually been auditioning to become a G.I. Jill. There were several G.I. Jills in different theatres, and they were tasked with being the female mouthpiece for Armed Forces Radio. Allen became the trusted voice for CBI, which was the China, Burma and India Command, broadcasting five to six days a week for upwards of an hour a night.

As G.I. Jill, her responsibility was to relay the information given to her by the Army and to try, as best as she could, to debunk all of the false declarations the enemy made about the state of the American war effort. In particular, her job was to counteract the work of the Japanese propaganda machine, especially Radio Tokyo and the group of English-speaking female radio broadcasters known collectively by Americans as “Tokyo Rose.” Although these Japanese women had virtually nothing to do with one another, their collective radio broadcasts spread rumors of sunken American vessels, failed American offensives and disaffected G.I.s deserting in record numbers. It was Allen’s job to fight back against such dispiriting claims, as specifically as the Army would allow.

“I could not let those boys believe a single word that Tokyo Rose said,” she remembers. “I had to be upbeat and never let them know anything that might affect them negatively.”

It was not glamorous work, and Allen often had to do her radio broadcasts in the evenings, after she had put in a long day at her Red Cross job.

“It was hard — I was often very tired and had been on my feet all day,” she recalls. “But the response from the G.I.s was so great, and you couldn’t help but feel rewarded and anxious to go again.”

Working the microphone was far from her only responsibility, but the rest of her job was vague. She and three other women worked at what was known as “Repairadise Inn,” a Red Cross club that catered to technicians and mechanics who worked for Army Air Transport Command, servicing the many C-46 and C-47 cargo planes flying through the treacherous Himalayas. Although the men coming to Repairadise Inn were not fighting on the front lines, the lives of all those “flying the Hump” rested on their efforts, and so the work was stressful and the hours long. Allen and her colleagues were expected to entertain the enlisted men of the Army A.T.C. when they were off-duty. It was a responsibility for which her work with Ream General Veterans Hospital and the Red Cross had prepared her well, but it still stretched the limits of her imagination.

“We went to famous shrines, the Taj Mahal, a leper colony, anything that we could find that was of interest,” she says. “At one point, our truck broke down in front of the leper colony and some of the G.I.s went in out of sheer boredom. At that time, we thought leprosy was highly contagious, and we were so scared that those men had caught it. We made them promise to burn their clothes when they got back. And, as it turns out, it’s not very contagious after all!”

One of her favorite diversions was the dances that they would hold. The women had all been told to bring evening gowns for just such occasions, and Allen says they were worn to tatters. Everyone loved dancing, even in the sweltering heat and the stiff competition for a dance partner.

“We had a rule that a man couldn’t cut in on a dance until a woman got to take at least 15 dance steps with her current partner, and anyone who violated the rule wasn’t allowed to dance anymore,” she says. “So you had this long line of guys, all counting to 15 and trying to patiently take turns.”

Although Allen and her colleagues were not on the front lines of the war, there were still many difficult and dangerous moments. The camp was infested with all manner of pestilence, including a scorpion that took up residence in the women’s bathroom. There was a polio epidemic that, with no cure and no vaccine yet available, left the entire camp paralyzed with fear. Disease was a constant co ncern. At one point, Allen contracted dengue fever, a mosquito-borne illness that causes fever, headaches, vomiting and body aches. Even after a five-day hospitalization, she continued working in a daze, never telling anyone how poorly she still felt.

“There was a word we women in the Red Cross always used — stalwart,” she says. “So I couldn’t complain.”

In some instances, the difficulties were man-made. At one point, Allen learned she was the subject of a vicious rumor that had her having an affair with a married officer, a story that had the potential to endanger her position with the Red Cross. Allen says such rumors were common, and they definitely drove home how different things could be for women compared to men deployed overseas during this time.

“I decided the best way to manage the rumor was to wear an engagement ring that really belonged to my friend and pretend I was marrying a sergeant,” she remembers. “I had met this man at a dance in Palm Beach, a very attractive fellow, and I had kept up correspondence with him and knew he was stationed on Okinawa. I t old people he was my fiancé, but I didn’t tell him I was doing that!”

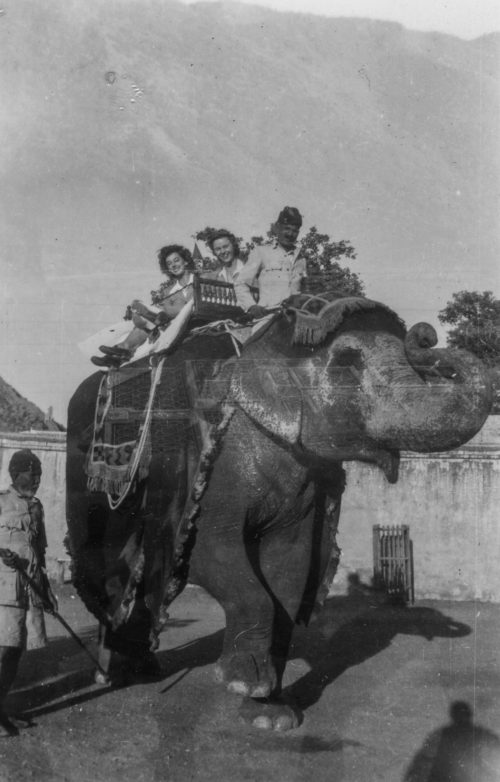

Allen also recalls the time that she and her friend, Jane, were invited to visit Jaipur as the guests of the Maharaja and Maharani of Jaipur, an experience that she recalls with great affection.

“I have no idea why we were invited — we hadn’t really done anything to deserve the invitation,” she says, still marveling that she got to have this novel experience, particularly in a time of war.

There were a large number of British attendees, and Allen remembers that she got to take her first bath in a long time. She and Jane put on their tattered evening gowns and enjoyed an endless stream of activities and American, British and Indian delicacies, as well as a polo match and a ride on the Maharaja’s personal elephant. When it was over, Allen and her friend were whisked back to the Red Cross camp in Agra, making it seem like the whole thing had been a dream.

Once the war ended in Japan in August 1945, Allen’s adve ntures only continued. As the United States and Japan struggled to hammer out a peace treaty and negotiate the difficulties of occupational rule, American servicemen lingered in the Pacific. With so many other G.I.s going home, there was a real need to keep the men entertained and happy, so show business personalities were enlisted to put on performances for the various troops and personnel still stationed in China, Burma and India.

Shortly after the Japanese surrender, Allen received orders from the Red Cross headquarters in Calcutta, ordering her to report for, of all things, an audition. Col. Melvyn Douglas, best known at home as an Oscar-winning actor, was interviewing all female personnel in the region for roles in an upcoming play. Convinced she’d be returned in a couple of days, she didn’t bother saying goodbye to Jane, who agreed to ship her things if she were chosen for the play. She didn’t see Jane again for nearly 40 years.

To her surprise, Allen was chosen for two shows: she had a part in “Call Me Mister” and was later cast as one of two female leads in Douglas’ production of the Noel Coward play, “Private Lives”; her co-stars were both trained stage actors from New York. They had little to work with — no microphones, sets made of sheets and so little money for costumes that Allen’s was made from a dyed parachute. According to Allen, the shows were incredibly well received by the G.I.s, who did not care about the poor production values.

“I had a taste of what it was to be a star,” says Allen. “Every day my cubbyhole of a dressing room was filled with flowers and notes. I’m not sure if we were actually any good or whether they just liked the short-skirted costumes on all the pretty girls.”

The players were ordered on tour with their show, and they traveled throughout India, where they were met at every turn with adoring G.I.s, vying for attention. At one stop, Allen recalls, the G.I.s used the camp’s pet tiger, Sugar, to scare the women. When they all scrambled for safety, certain men, who had won a prearranged lottery, were there to comfort the women and calm them down. The following day, the whole acting troop was formally introduced to Sugar, displaying much more friendly behavior.

After the tour for “Private Lives” ended, Allen was sent back in Calcutta performing in midnight horror shows for Armed Forces Radio. At that time, India was on the verge of a full-scale rebellion against its British colonizers, and Allen found herself right in the middle of the conflict.

“One night, in the home where I was staying, I smelled smoke. I looked out of the window and saw torch-laden Indian nationalists invading our streets, which were in an English neighborhood, and they were setting fire to the houses,” she says. “Always a Red Cross stalwart, I picked up the phone, praying it would work, and somehow word got through and we were rescued by the military police, and luckily our house was spared.”

From Calcutta, Allen was called to China to receive new orders. She embarked on an odyssey that took her from Thailand to the Philippines before finally landing in Shanghai, where she was transferred to her final Red Cross club in that city. However, her time there did not last long — the communist uprising that ultimately consumed the nation in 1949 had already begun, and, with Mao Zedong and his revolutionaries on the outskirts of the city, Shanghai was not exempt from the commotion. Amidst the political upheaval, the Red Cross began a slow evacuation of its employees back to the United States.

When Allen left China in late 1946, she was once again consumed with a tropical disease, this time of unknown origin, and she spent most of her trip home sleeping. Although she was overjoyed to be reunited with her family back in the States, she recalls her initial arrival in San Francisco as rather underwhelming.

“I had pictured a welcome home band and people waving,” she says. “Instead, we were just one of many ships returning from ‘somewhere’ in the Pacific.”

After Allen returned home, she reconnected with her erstwhile “fiancé,” J. Scribner “Scrib” Allen, whose existence she had used to combat the salacious rumors in India. She and Scrib had intermittently kept in touch throughout the war, although he remained blissfully unaware that she was advertising herself as his future wife the entire time. Now that both were home in the States, they began speaking on the phone regularly.

Allen says everyone at that time was anxious to pair off, and she had multiple suitors vying for her hand. Ultimately though, it was the handsome, dashing Scrib that won her heart. The pair married in March 1947 and settled in Pittsfield, Mass., where Allen worked as a public relations director for the Berkshire County American Red Cross before staying home with the couple’s two children, Jeffrey and Pamela. The family moved all over the country as Scrib climbed up the corporate ladder at General Electric as an international electrical engineer, eventually serving on the President’s Advisory Council for Energy through four administrations. They lived in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington, D.C., Vermont, California, Florida and Minnesota, where Allen still lives today. Everywhere they went, Allen threw herself into volunteer, public relations and fundraising activities that spanned every possible interest, from fine arts to athletics to children’s activities. She also remained faithful to William & Mary, staying in touch with many of her college friends and cherishing the memories she made there. Even now, 78 years after graduation, recalling her time in Williamsburg brings a tear to her eye.

No matter where she went, Allen found that there was universal interest in her story, a tale of adventure in a time where women were not expected to have such experiences. In 2007, Allen became one of 40 veterans profiled for the Veterans History Project, created by the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. It was only then that Allen realized she was considered a veteran. On the cusp of her 99th birthday, Allen is still incredibly active, an enthusiastic swimmer who continues to give interviews and presentations about her experiences during World War II.

She and Scrib were married for 50 years — he passed away in 1997, shortly after their golden wedding anniversary. Although he’s been gone for 21 years, she still sleeps with a photo of her soldier, forever immortalized in his uniform, at her bedside.