Silent Stories

Soldiers and veterans at W&M speak up

May 3, 2019

By

Noah Robertson '19

Silent Stories

Soldiers and veterans at W&M speak up

Charles Bowery ’92 stood among flags and headstones, waiting in Arlington National Cemetery for the funeral of Jim Dorsey ’60. • For 25 years, Dorsey served in the U.S. Army, completing two tours in Vietnam and retiring as a lieutenant colonel. After his military career, he worked at Jamestown Settlement and lived in Williamsburg, Virginia. Dorsey was a regular at campus events and football games, driving a truck covered in W&M decals.

A few years before his death, Dorsey approached the Alumni Association with plans to relaunch the Association of 1775 (Ao75), William & Mary’s military, veterans and government alumni group, which had been inactive for years. Around the same time, Bowery had a similar idea, and behind the scenes they worked to reinvigorate the organization.

Ao75 is now back in action and moving forward.

Networks are strengthening and infrastructure is growing. Part of a larger, campus-wide focus on William & Mary’s veterans services, Bowery, staff across campus and others are working hard to improve the organization, sometimes on nights and weekends.

But Dorsey, who passed away in January 2018, didn’t see the results of their success. He saw only preparation, a glimpse of the vision: to give those who’ve served and sacrificed so much the community they deserve. That vision, though, was the first step toward the eventual reality. By believing, Dorsey helped others see.

So Bowery stood there, on the dry, cloudy January day, and waited to tell the story of Jim Dorsey, one story of thousands in a nearly 250-year university legacy; a veteran, a William & Mary graduate, a man who made his nation — and his alma mater — proud.

244 Years

William & Mary’s history with the U.S. military began before the United States existed itself. In 1775, a group of students organized a militia unit, and two years later, even while exempt from military duty, students and faculty formed a College Company for service in the Continental Army.

They called it the “William & Mary Company.”

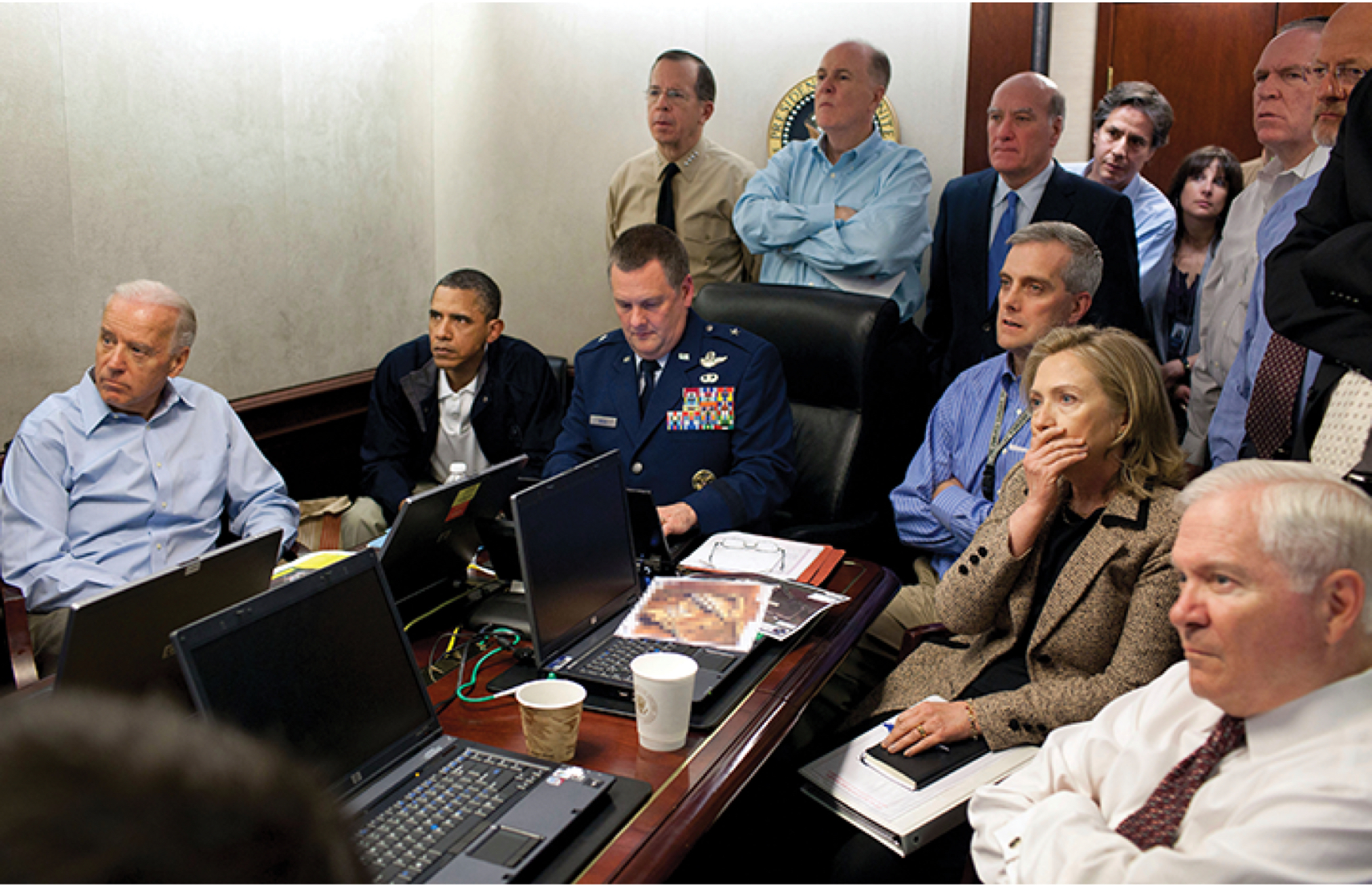

George Washington was the university’s first American chancellor, and James Monroe, an officer on Washington’s staff, is an alumnus. William & Mary graduates helped earn America’s independence and for centuries have fought to preserve it. After all, Chancellor Robert M. Gates ’65, L.H.D. ’98, while serving as Secretary of Defense, was sitting across from President Obama on the night Osama Bin Laden was killed.

And not only have university graduates served in every major American war, the university itself has transformed because of them. It took herculean efforts from university President Benjamin Ewell to rebuild campus after it burned during the Civil War. World War I led to the university admitting women for the first time in 1918, and after World War II, William & Mary opened up the St. Helena Extension in Norfolk for returning soldiers continuing their education. Lewis B. Puller Jr. ’67, J.D. ’74, who lost both legs and much of his hands during the Vietnam War, won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography, “Fortunate Son,” which began as an article for the William & Mary Alumni Magazine. Two alumni, Ryan McGlothlin ’01 and Todd W. Weaver ’08, and one MBA student, Kyle Milliken, died while fighting in Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia, respectively. Their names are written on a plaque in the Wren Building, honoring fallen service members from the university.

Starting with militiamen in 1775, William & Mary’s legacy with the military continues 244 years later in 2019.

‘Another World’

Transitioning from military to civilian life has always been difficult, but a rapidly changing 21st-century landscape has made that adjustment even harder — especially for those resuming their education or reentering the workforce.

Phillip Sheldon ’20 is making that transition now.

In 1944, Sheldon’s grandfather landed on Utah Beach in World War II, lost a big toe to frostbite in the Battle of the Bulge and later helped liberate the Dachau concentration camp in Southern Germany. At the same time, his great-uncle was fighting in a Pacific-Theater submarine division, sinking ship after enemy ship. Members of his family have served in the military since the Revolutionary War, and when Sheldon came of age, he continued the tradition.

In April 2011, Sheldon enlisted in the Marines, hoping to be on the front lines. Two tours followed: one in Afghanistan and another in Romania. It was eye-opening — to encounter new cultures for the first time, to learn what it feels like to be shot at, to see firsthand that many don’t come home.

Sheldon finished his service after four years and returned to Virginia, where he started taking classes at his local community college and soon realized he could transfer to a four-year university. With multiple acceptance letters, he chose William & Mary.

Adjusting was a challenge. When you leave the military, you also leave a regimented schedule from sunup to sundown; facing the newfound freedom, many struggle with self-discipline.

Readjusting to the educational system itself was also difficult. Sitting in math and science classes, Sheldon would think about how he hadn’t attended a class, studied for tests or taken notes in more than four years.

Even for someone who considers his transition relatively smooth, Sheldon still encounters misperceptions from the public.

“There’s definitely a perception out there among some employers that returning veterans are damaged goods, and that’s just not the case,” Sheldon says. “People often approach you and think you’re some kind of killer or have PTSD, when in reality, many don’t even see combat.”

Sheldon’s time in Romania helped him gradually adjust out of the military in a relatively stable country. He says he can only imagine what it’s been like for his friends who returned to the U.S. after two tours in places like Iraq and Afghanistan and were discharged, after just a month of debrief on base, into civilian life.

“It’s like coming back to another world,” he says.

Bridging the Gap

Both the civilian-military divide and the difficulty involved in transitioning back into civilian life make veteran support services even more important, especially in the world of higher education. Compared to traditional students, veterans returning to the education system face systematic disadvantages.

According to a report from the Student Veterans of America, veterans returning to higher education are more likely to be older, have a family, work full or part time and have a disability. The National Institutes of Health estimates post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects anywhere from 10 to 31 percent of veterans. PTSD requires a personal and often nonlinear recovery process and can lead to substance abuse and depression. While the term is very general, both its symptoms and causes are unique, requiring individualized attention.

At the same time, according to Government Professor Lawrence Wilkerson, there is a growing national divide between military and civilian populations. The faculty advisor to the Student Veterans of William & Mary and a 31-year veteran himself, Wilkerson says military and veteran citizens make up less than 1 percent of the U.S. population, and in terms of average income and education, now have less in common with civilians than ever before.

Simply put, there’s a gap — between traditional and non-traditional students, civilian and military populations and both put together.

Since taking office last year, President Katherine Rowe has made improving the services offered by William & Mary for active duty and veteran students a top priority. Hosting discussions and listening sessions with these groups, Rowe is building on existing efforts and moving forward initiatives focusing on the future of work, knowledge and service.

“There’s been a decisive shift in energy with President Rowe,” says Corey York ’19, outgoing president of the Student Veterans of William & Mary. “She recognizes the progress that’s already been made, and is looking to build even greater momentum.”

In other words, one of Rowe’s top priorities is bridging the gap.

The Bridges

University services supporting veteran and military populations begin at the undergraduate level, with a focus on problem-solving, advocacy and leadership.

A few years ago former University President Taylor Reveley LL.D. ’18, HON ’18 established a working group to explore issues confronting student veterans. After a year-long study, the working group delivered its report but then stayed on to help address the outlined challenges. Patricia Roberts J.D. ’92, vice dean of the law school, initially chaired the group, and after two years, former Education Professor Jacqueline Rodriguez took over.

The working group, now open to everyone regardless of military experience, meets once a month and now has around 40 members, comprising faculty, staff, alumni and students. At each meeting, they discuss issues facing military and veteran members of the university — then they discuss solutions.

One of the group’s larger initiatives has been its Green Zone Training, a day-long program that educates faculty and staff on issues specific to military-affiliated students. Students in the Military and Veterans’ Affairs Working Group wrote the entire curriculum, and Rodriguez says not a moment was wasted.

“Our student veterans are tenacious, dedicated, persistent and loyal. They never take no for an answer. They always find a way,” she says.

The pragmatic problem-solving approach of the working group is mirrored by the Student Veterans of William & Mary, an advocacy organization for undergraduate student veterans.

A former Marine, Corey York attended his first meeting out of curiosity. By the night’s end, York had been elected president.

“I guess I’m president now,” he thought. “Let’s rock ’n’ roll.”

Working strictly as volunteers, York and others in the group mobilized students, faculty and administrators, resolving problems faced by student veterans and making the campus community as a whole more aware.

Ultimately, he believes traditional and non-traditional students each have complementary skill sets and form effective partnerships. Just as it’s said in opening Convocation, “those who come here belong here.”

“We’re all in this together in the end,” York says. “We’re all part of the Tribe.”

In addition, the university’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program, run through the Department of Military Science, gives students the chance to enter the U.S. Army as commissioned officers after graduation. The key to their curriculum, says Department Chair Lt. Col. Dustin Menhart, is leadership. Students enrolled complete the equivalent of 32 total credit hours, each semester building on the last.

“It’s not just push-ups and sit-ups,” Menhart says, surrounded in his office by memorabilia from his almost 20-year career in the Army. “The bottom line is that we’re just like any other department at the university.”

ROTC isn’t easy, and neither is it meant to be. It takes sacrifice and discipline, training at 5:45 a.m. regardless of the weather and enduring whatever six-mile run lies ahead. It takes accepting the equivalent rigors of another major, in addition to students’ other coursework. It’s difficult — but according to Menhart, difficulty builds resilience and teamwork builds leadership. ROTC students emerge from their four-year crucible prepared for the sacrifice and commitment required ahead.

Capt. Emily Bessler ’14 of the Army’s 25th Infantry Division relied on the skills she learned in ROTC when she was commissioned five years ago. When she arrived, there were only two women in her battalion; when she left, there were 15.

“I told my guys from the get-go, ‘I’m just another lieutenant — don’t change your vernacular or behavior on my account,’” she says. “I want them to treat me the way they would any man, and the

fact that they do is the greatest compliment they could give me, and affirmation that I’m doing my job the best way I know how.”

“What you learn in the military often helps in the classroom, especially discipline and leadership. The marines have an old saying, ‘adapt and overcome.’ if the mission changes, we’re ready for that, in the military or our careers.”

‘The Best of the Best’

The university’s military and veterans services continue at the graduate-school level, where William & Mary continues to receive statewide and even national recognition.

“They’re the best of the best,” says Amanda Barth M.Ed. ’06, the director of MBA admissions at the Raymond A. Mason School of Business for their active duty and military students. “And our services for them are unparalleled.”

The business school’s MBA programs are widely recognized for their attention to the needs of ser- vice members. It’s a combination of simple things done well and a personalized approach that sets the programs apart. They host a yearly Veterans Day celebration and recognize students’ promotions with special events, but they also give military applicants high-priority status and understand their often non-traditional backgrounds. Through personalized career counseling and alumni networking, the business school helps military and veteran students build on the strengths they already have.

The business school’s services have continuously attracted military and veteran students, so that they make up more than 20 percent of the student population in each of the three MBA programs That service and commitment to military members of the student body is paralleled by programs in the School of Education.

In 2018 the school received a five-year, $1.9 million state grant to continue its Troops to Teachers program, training veterans for second careers in K-12 education. Launched as a pilot program in 2017, Troops to Teachers seeks to address Virginia’s statewide teacher shortage by training veterans, a group uniquely suited to that field.

“What you learn in the military often helps in the classroom, especially discipline and leadership,” says Charlie Foster M.Ed. ’17, the program’s veteran liaison and a Marine himself. “The Marines have an old saying, ‘adapt and overcome.’ If the mission changes, we’re ready for that, in the military or our careers. At the end of the day, it’s all service.”

During the grant evaluation process, William & Mary’s Troops to Teachers branch was given an A+ rating and labeled a “rock star program.”

And it’s not the only program they offer.

Over the next year, the School of Education will develop a master’s degree in military counseling, working with a nearly $300,000 state grant. Mental well-being, they believe, is the foundation for success, and the program will help those who have sacrificed so much continue to live healthy lives.

“Be there for veterans you know and listen to them as much as you can,” Foster says. “There’s a lot to learn, there are fantastic stories only they can tell. The only way to understand their sacrifice is to talk and listen.”

‘Shouting it from the Rooftops’

And then there’s William & Mary Law School, which ranked on the list of Top 10 2019-2020 Military Friendly Graduate Schools this year. Its veterans services aren’t just well-known, they’ve become a national model.

Just ask James.

Asking to be referred to only by his first name, James is a former military policeman in Iraq. After returning from his tour of duty, James suffered a heart attack, related to a pulmonary embolism, in his mid-30s which doctors said stemmed from a time he fell sick while in the military. He couldn’t find insurance, at least none cheaper than his already enormous medical bills. People with his condition, he says, have a 50 percent mortality rate within five years.

“I thought I was going to die before anything was going to be figured out,” James says. “There’s a saying people applying for disabilities claims have: ‘delay, deny and hope that I die.’”

Not only is the paperwork arcane, but James says the application process is wildly inconsistent. Forms are often rejected without explanation; some claims get approval within months, others years. Early on, James was told by a representative that he’d be lucky to get an aspirin.

"We're all in this together in the end. We're all part of the Tribe."

Then a family friend told him about the law school’s Lewis B. Puller, Jr. Veterans Benefits Clinic. And everything changed.

The Puller Clinic’s mission is to advocate for veterans navigating the Department of Veterans Affairs disabilities claims process. While working with full- time veterans’ law attorneys in a three-credit course, students in the clinic provide free legal representation to two or three clients a semester. Students get intensive hands-on training, and their clients get invaluable advocacy.

The Veterans Benefits Manual is over 2,000 pages, and those applying are often already struggling with a physical or mental ailment, which for non-experts can make an already difficult process nearly impossible.

At the same time, Hampton Roads has the most densely distributed military population in the U.S., with more than six active military bases, over 100,000 active-duty and reserve personnel and thousands of veterans. It’s a perfect home for the program.

James applied to the clinic around 2010, paired up with a representative at the law school and immediately felt a sense of relief. The clinic provided support, expertise and persistence and helped to navigate a complex system, filing necessary paperwork and overcoming obstacles. Even with the clinic’s help, James is just now receiving his government benefits.

“It was nothing but frustration beforehand, like beating your head against a wall. There’s no way I could have stuck with it this long,” James says. “I don’t like to think about a world without the clinic, but honestly without them, I’d probably be in a room at my mom’s house right now trying to find money for blood thinners.

“They basically saved my life.”

Through a partnership with Starbucks, the Puller Clinic also hosts select Military Mondays for veterans working through the claims process. The program, which has since been recognized and replicated nationwide, provides free legal consultations over coffee for veterans in the local area. Each year, Military Mondays provides nearly $50,000 worth of pro bono legal services, assisting more than 360 veterans since its inception in 2015.

“This isn’t assistance, this is what veterans are entitled to because of their service,” says Patricia Roberts, who is also co-director of the Puller Clinic. “I don’t know if I have adequate words to convey the sense of admiration I have for the sacrifices they make. I just try to sit and talk, listen and say it’s an honor to meet them.”

The Faces

Bowery is standing at the funeral, still waiting to tell the story of Jim Dorsey. Dorsey, of course, was an exceptional man, but there are thousands of other stories waiting to be told. They make up a legacy so wide and deep there’s no one way to understand it. No one story is enough.

Every service member at William & Mary is a part of that legacy. Each of their stories is part of a larger, changing narrative, which at the same time is the story of our nation, the story of the university and the stories of millions of lives, all worth our eyes and ears. That legacy — of patriots, warriors and leaders — is always in its next chapter, always waiting for its next story.

“It’s not about just one face, it’s all the faces. You can’t always tell if the people around you are veterans, and the thing that’s upsetting is not being able to honor each story,” Foster says. “It feels like sometimes there’s just not enough time. We owe service members and veterans more than a thank you. But, you know, if we all listened, all asked questions, then hopefully that would be enough.”

Dorsey’s family didn’t know Bowery was coming to the funeral. In fact, that was the first time he ever met them. But he wasn’t going to let a member of the community pass away unnoticed. He wasn’t leaving a story untold.

Bowery came to the funeral to represent the Association of 1775, which plans to honor Dorsey with a scholarship in his name. Bowery came to honor a member of the William & Mary legacy. Bowery came because he had a story to tell.

Editor’s note: In the hard copy of the magazine, Charles Bowery’s class year was listed incorrectly. He is from the Class of 1992, not the Class of 1993.