Broadcasting the World

gayle yamada ’76: A Storyteller’s Tale

January 7, 2020

By

Ashley K. Speed

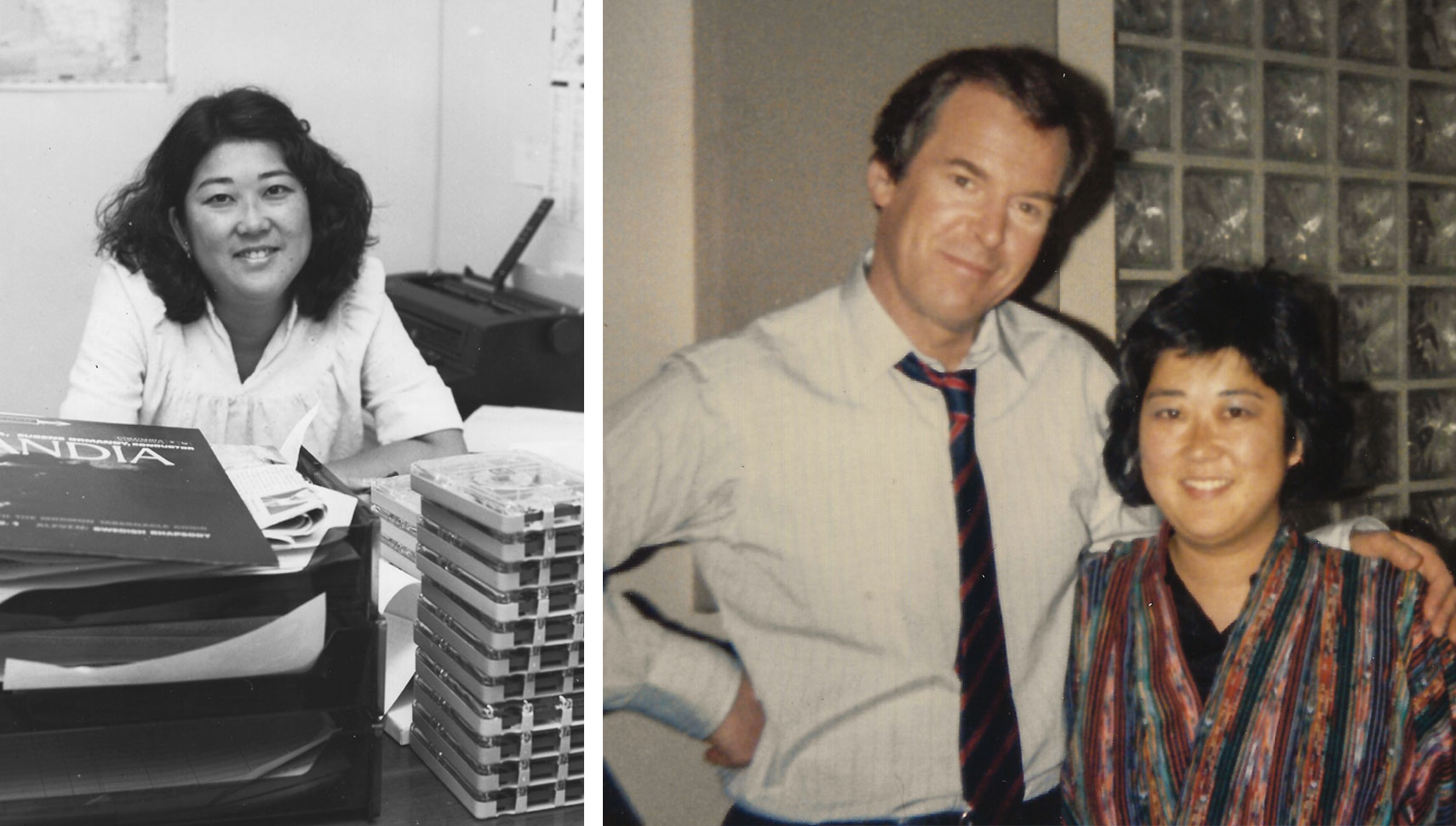

gayle yamada ’76 has told stories for most of her life. Some were shared from behind an anchor’s microphone or news producer’s chair, while others were played over the airwaves — the shelf life of some as fleeting as an evening sunset, their impact unknown.

“In broadcasting you never know how many people hear you,” yamada says. “You never know how you might have changed lives. I was interested in changing lives, but I didn’t necessarily need to know that I had changed anyone’s life.”

yamada is an award-winning broadcast journalist who has spent more than four decades in the industry. She’s done just about every job one can in a newsroom, covering topics from street artists in San Francisco to cooking to documentaries on music and dance. She has also taught at universities, was a columnist for a newspaper and co-authored two books.

yamada says it’s important to her to tell the stories of underrepresented people to a broader audience.

“I think the theme of my whole career has been to give voice to people who have never had a voice,” yamada says.

Storybook

Her journey to becoming a broadcast journalist started in the traffic department of KCBS radio station in San Francisco after she graduated from William & Mary. She began volunteering in the news department and soon was hired, and she rose quickly through the ranks.

“The word that comes to mind when I think about gayle is integrity,” says Diane Keaton (not the actress), who worked with yamada at KCBS. During the time they worked together at KCBS, the Jonestown massacre and Moscone-Milk assassinations occurred. “So many stories we were doing as a station at the time required real tenacity, knowledge and sensitivity to cover and make sure we got all sides of the story. I remember gayle as someone I looked to for her integrity in coverage.”

In the early 1980s, yamada worked on “We the People” with Peter Jennings, a four-part series on the U.S. Constitution. Initially hired as a researcher for one of the parts, the quality of her work led to her becoming the series’ associate producer.

“Here we were talking about the Constitution, the underpinnings of our nation and of us as a people,” yamada says. “It taught me the importance of stories, no matter how old they are or how distant they may seem.”

In 2001, yamada told the story of Japanese-American World War II veterans in “Uncommon Courage: Patriotism and Civil Liberties,” a documentary that was broadcast nationally on PBS.

“What these men did to help conquer Japan while their families were imprisoned in the United States is inconceivable; despite racial discrimination and being stripped of their civil rights, their patriotism prevailed,” yamada says. “My father was one of these soldiers.”

yamada says she loved the challenge of telling the story fairly.

“I made many lasting friendships and their story showed me resilience and determination in spite of overwhelming odds,” she says.

on “We the People” with Peter Jennings. The documentary was a four-part public television series celebrating the 200th anniversary of the U.S. Constitution.

Distinct Letters

yamada, who lives in Davis, California, began lowercasing her name when she was around 12 years old and legally had it changed decades later.

“I wanted to be distinctive,” she says. “I didn’t really realize that I was already distinctive. At the time I thought, ‘Why should names be more important? Why should you capitalize things to emphasize them?’”

When yamada arrived at William & Mary in the early 1970s, she recalls that no one looked like her. The student body was mostly white and only had a few African-American students at the time, she says. yamada says this didn’t

negatively impact her W&M experience because she was confident in who she was, in part because of the strong sense of pride instilled by her parents.

“My parents taught us to value our cultural heritage,” yamada says. “I was always proud of being Japanese American.”

She says her W&M education taught her to think critically as well as to appreciate the importance of the arts and humanities.

“I learned how to tell a story, no matter what medium you use,” yamada says.

Lasting Impact

While yamada has spent her professional life telling the stories of others, it blends into her personal life. Her son, Drew, died when he was just five days old which, coupled with a stroke she had before he was born, was one of the most traumatic times in her life. Out of adversity came opportunity; his life, though short, is having a great impact on generations of W&M students. yamada, her husband David Hosley and daughter Heather created the Drew Yamada-Hosley Scholarship for International Study and Travel.

“We established this scholarship in his name that will keep Drew alive forever. William & Mary really gave me a foundation for lifelong learning and we would like our son’s legacy to be one that can change lives,” she says.

A Legacy of Stories

yamada recently completed a Ph.D. at the University of California, Merced. Her degree is in interdisciplinary humanities, focusing on power and Latinos.

“She was always scrupulously prepared, but the most important thing is that she had an intense curiosity and she would really dive into what we were discussing and ask very compelling questions,” says yamada’s advisor, UC Merced Provost Gregg Camfield.

yamada is currently working with Stanford University to archive a few hundred tapes and documents of stories she owns that she has either produced, reported or written throughout her career.

“I’ve been concerned that the interviews I’ve done over the years are going to die with me,” yamada says. “You start to think about what kind of legacy you are going to leave and who can benefit from your work.”

The stories at Stanford will be available for students to study — a rich resource for future generations of storytellers like yamada.