Joseph Levine ’18 and John Gerlaugh sat in a boiling hot mud-brick building asking the same 120 questions again and again. Their work, taking place in the capital of Afghanistan’s Panjshir Valley, was part of a research survey that had come to resemble a high-stakes game of telephone. Gerlaugh asked a question, their translator interpreted, the interviewee responded, their translator interpreted again, and Levine transcribed. It was painstaking, Gerlaugh thought, but worth it in order to understand the needs, routines and behavior of the local public.

Power Analyst

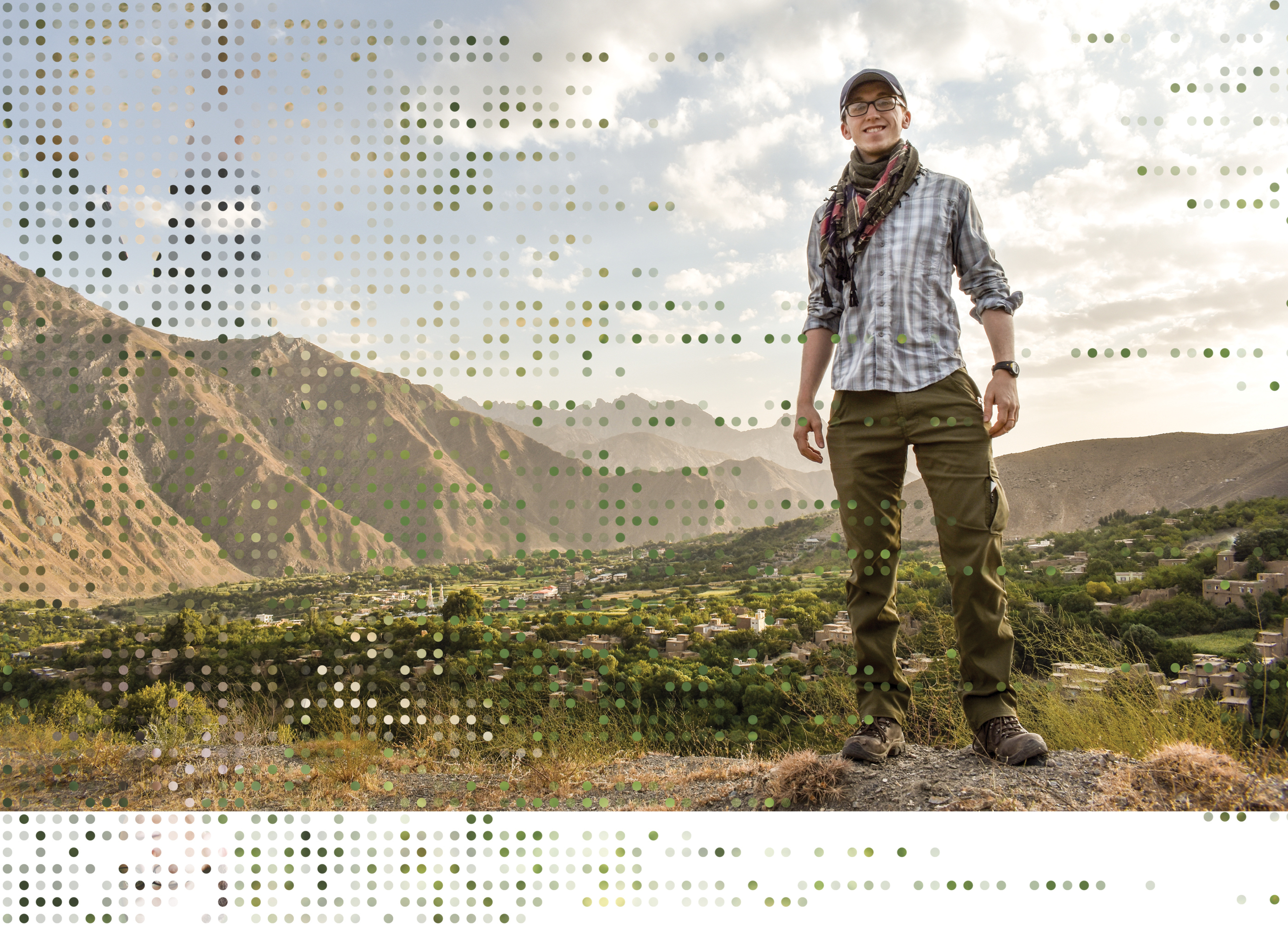

Joseph Levine ’18 and Team Afghan Power help electrify rural Afghanistan

September 15, 2021

By

Noah Robertson '19

Amid the process, though, Levine asked them to stop and pulled Gerlaugh aside. The answers were starting to fall into predictable patterns, he said, which made him suspect that respondents were exiting the room and telling the next participant what to say.

His assumption proved true, and he and Gerlaugh changed their process to stop that from happening. That one observation saved the dataset and days of work. Even more, Gerlaugh says, he wouldn’t have noticed it without Levine.

“He brought an analytical view of the data that we just didn’t have before,” Gerlaugh says.

The survey was part of a weeks-long trip to Afghanistan for Team Afghan Power, a nonprofit Gerlaugh founded in 2015 to support rural parts of Afghanistan by building microgrids in areas that wouldn’t otherwise have access to electricity. Gerlaugh, a former director of counterterrorism during the George W. Bush administration, had long-standing connections to the country that motivated him to focus there.

But Levine didn’t have those connections. In fact, when he made his first of two trips to Afghanistan, he had just graduated college. He’d never visited the country. Growing up, his family barely traveled.

To Levine, that’s never been a problem.

In his time at William & Mary and after graduating, Levine has traveled the world researching international development. His work has taken him from India to Afghanistan to Sierra Leone, but in each country, he brings the same analytical toolkit and ardent work ethic that helps the projects succeed. It’s a skillset he learned in his four years studying at William & Mary and the University of St Andrews, as part of the joint-degree program.

Levine knows that his individual work won’t solve entrenched issues of poverty and instability in the developing world. He wants to be part of the solution, though, no matter how long that may take.

“That’s the whole point of research,” Levine says. “What’s going on right now is not an acceptable outcome. But let’s think of ideas that’ll change that, and then test every single one of them until we find one that works.”

Levine grew up in the Washington, D.C., area, with his family split between Bethesda, Maryland, and parts of West Virginia. Living near the star of William & Mary’s geographic solar system meant a lifelong exposure to the university. But it was the St Andrews Joint Degree Programme and the government department’s influence in Washington that pulled him into its orbit.

“Williamsburg is not exactly the center of the world,” says Levine. “But there were connections everywhere at the university.”

He developed connections of his own through an internship with the Project for International Peace and Security, which is part of William & Mary’s Global Research Institute, and his constant appetite for information on government and international relations. Last year, he even reread one of his old textbooks on Soviet politics.

Spending his sophomore and junior years at St Andrews expanded his cultural literacy and provided his first gateway to life abroad. Moving from Green and Gold Village on William & Mary’s campus to Scotland was like having a second freshman year. The social atmosphere was new — and the fencing club, where he competed in épée, was much more intense. The students at William & Mary, from a similar area and with similar career goals, helped him build on existing ideas. The students at St Andrews introduced him to new ones. The combination taught Levine to adapt.

“I’m happy pretty much anywhere I am,” he says. “But I think William & Mary really set me up to be productive and happy.”

Productive and happy Levine has been, partly because of the enjoyment he gets from seeing new places. Traveling to Europe was fun, he says, but after a while it felt too close to the culture in which he grew up. Part of his reward in traveling is finding a challenge and growing from it. Levine didn’t feel challenged, so he looked elsewhere.

His first foray came in the form of a State Department language fellowship to Calcutta, India. There the native language is Bengali — the seventh-most widespread language in the world but one with a small footprint in the United States. He spent the summer of his sophomore year in the city, ensconced in the culture and language.

“I really like finding a new place to find out what was challenging about it,” Levine says. “It’s all driven by similar research topics, similar tasks, trying to make the same kind of difference.”

All this came as a surprise to his family, who rarely stray from home. Both of his sisters now live close to their colleges. His family is still in the Washington area. Meanwhile Levine hasn’t lived in the same place for more than 10 months since high school.

“I am the weird one,” he says.

Whether weird, or just different, Levine’s travels led him to parts of the world he would’ve never seen and people he would’ve never met.

One of those people was John Gerlaugh.

A former Marine Corps officer, Gerlaugh has spent his life in and around the U.S. military, and in style he meets the mold. His conversational tone is that of a friendly command. When he believes something, he believes it boldly. That means acting on it.

For most of his life, Gerlaugh believed the best way to ensure peace abroad was to use force. But in the middle of the 2010s, while studying for a master’s degree at National Defense University and debating kindhearted professors, Gerlaugh changed his mind.

“I did a complete conversion to economic development,” he says.

That change of heart led him to found Team Afghan Power. Unlike other non-governmental organizations

Gerlaugh knew, the aim wasn’t to just raise aid money. In his time in Afghanistan, he’d seen what happens

when American infrastructure projects proceed without community support — whether that be a wind farm

left in disarray after the village couldn’t maintain it or an unwanted well destroyed by jaded locals. His team would be on the ground, working on projects with and for the Afghan people. To him, sustainability was the gold standard.

After extensive research, he decided the best way to contribute was by building microgrids. Afghanistan is still a heavily rural country, and the infrastructure required to power remote villages on a large scale is still prohibitively expensive for the Afghan government. By providing electricity, and the tools to effectively use it, he reasoned, they could benefit people for generations.

Soon after Gerlaugh laid the foundation of Team Afghan Power, he and Levine were introduced through a professor at William & Mary. They set up a breakfast meeting in Fairfax, Virginia, over French toast, bacon and coffee — a meal that has since become their staple. Gerlaugh explained his long-term vision and listed areas where Levine could help. It was an ambitious project, Levine thought at the time, but he liked the sound of something big.

“I have a three-week trip to Afghanistan coming up,” Gerlaugh said. “Do you want to come?”

Levine said yes.

Almost a year later, their plane touched down in Kabul International Airport, surrounded by some of the country’s most impressive mountain ranges. The area’s altitude can disorient new visitors, so they spent half a week there in the beginning before driving the daylong trip to the Panjshir Valley, on the route Alexander the Great once crossed to conquer India.

Despite some concerns about safety (which required thorough reassurance to his parents), he felt overwhelmed by the hospitality and resilience of those he met. New acquaintances almost always invited him to tea and a meal, offering him the best watermelon he’s ever had. Local children turned the abandoned tanks and downed helicopters that littered roadsides into playgrounds.

In Panjshir, they linked up with Team Afghan Power’s engineer, who lives in the country, before driving to the region’s capital to stay with the governor. Then the work began.

“The day-to-day was about half political, half engineering,” Levine says.

Any electrical project requires the approval, and trust, of different departments, officials and local leaders, at different times and at different levels. They studied maps to identify potential sites, and then went for inspections and interviews to better understand the economic behavior and needs of local people. Surveys, inspections, data collection and long flowcharts became, to them, a way of life.

Working with limited supplies did too. Some of the towns they visited built small hydroelectric plants out of little more than a truck axle. “You kind of have to jerry-rig most things,” Levine says.

Improvised solutions also often meant improvised roles. In his work on the ground, Levine became the team medic, photographer, analyst and scribe. His affability helped build trust with skeptical villagers, especially when their kids rushed out to play with them. His analytical thinking helped sharpen ideas.

“He’s like a Swiss Army knife,” Gerlaugh says.

It wasn’t until the end of Levine’s first trip to Afghanistan, though, that Gerlaugh knew he’d found a special partner. After the exhaustion, heat, drudgery and sweat, as they flew back from a largely self-funded trip, Levine asked him when they could go again.

In the summer of 2019, they did. This time, having established their relationships with locals already, they completed a more structured set of surveys and data collection. The work, as usual, wasn’t glitzy. The hours were still long. The days were still hot.

Joining them this trip was Curtis Lee, a retired Marine colonel who had joined the project after serving with Gerlaugh in Afghanistan. Immediately, Lee says, he saw how Levine had Gerlaugh’s “complete and total trust.” That was enough for him.

So focused on developing relationships with the Afghan people, their work also led to close relationships of their own. Lee came to admire Levine’s self-sufficiency, humility and attention to detail. He still calls him “Jo.”

“Jo’s ability to fit in with a couple guys like us and to tolerate all our old war stories and everything is a real testament to his ability to operate in different environments,” Lee says.

Levine jumped into his work, and while rarely the first to talk, wasn’t afraid to voice his opinion. The team didn’t always agree, but they respected each other’s thoughts and came to know each other as equals.

“Frankly, he became one of my best friends,” says Gerlaugh. “I’m 67, so I don’t often make friends with 23-year-olds.”

A 40-year gap in age made little difference while working on the same project. The challenges were enough to unite.

Since the pandemic began, the Afghan government has grown weaker and Taliban has grown more aggressive. Each trend makes Team Afghan Power’s work more difficult. They’ve had to delay trips and relocate their efforts, at times fearing for the long-term safety of their local partners. Fundraising is a persistent challenge, as is the moral injury some with military experience in Afghanistan feel about the long war effort still wrapped in uncertainty.

“The scar is deep,” Gerlaugh says. “But programs like Team Afghan Power are how we’re going to fix

it.”

These setbacks were part of what made their first finished microgrid so rewarding. It didn’t end up in the Panjshir Valley, instead moving to the Bamyan Province for the sake of safety.

There the five-kilowatt grid powers a local all-girls school, with about 300 students K-12. The system of solar panels is protected against the elements, and power lines run underground for safety. In addition, they supplied computers, internet access, a copier and a television that functions as an electronic blackboard.

Now they have their eyes toward another nearby school, which serves more students and doubles as a health clinic.

“If we can bring the outside world in the form of a high-quality education, we’ll affect generationally the outlook these kids have,” says Gerlaugh.

Levine is watching from the outside for now. Since his last trip to Afghanistan, he took a job in consulting in the private sector around Washington and spent about a year there. Then, yet again driven by a desire to research, he quit and decamped to Sierra Leone, where he’s spent the first half of this year working as a co-author and researcher on different projects related to international development, including one with a former professor.

S.P. Harish is an assistant professor in the university’s government department and has worked with Levine ever since Harish needed a student to accompany him on a two-month summer research trip to rural India. Levine joined him first as a research assistant and then as a co-presenter at a conference in Puerto Rico.

“William & Mary has a fantastic system of allowing professors like me to take students like Joseph into the field and give them a taste of what research is,” says Harish.

On their trip to India, Harish and Levine talked about different research ideas on a car ride — a discussion Harish forgot about until years later he got a call from Levine asking him whether he wanted to put them into action. Harish agreed and they’ve spent the last year and a half working together, as co-authors this time.

“It has been amazing to work with someone who is so driven and so intent on staying on top of things,” says Harish. “He’s the ideal co-author.”

Thanks largely to Levine’s work — including on a recent three-layover flight back to Washington from Sierra Leone — their project will soon see the light of day. Sometimes, he even pushes Harish to work harder.

Levine doesn’t know where his next destination is, but he knows that regardless of his location, the aim will be the same.

On one hand, he’s preparing to pursue a Ph.D., in the hopes of synthesizing his research into a shared body of work. On another, there’s a mission to his method.

“The usual example I give is South Korea,” Levine says. “In the 1970s, South Korea had the same GDP per capita as Sierra Leone today. That was crazy, right? No one really has a plan to get Sierra Leone to be as rich as South Korea, but we’re trying to think of this as a big picture. For now, the best thing I can do is help fix what I can help fix.”

That may take him farther; it may bring him closer to home. But no matter what, there will be a part of Levine in Afghanistan. Whether it’s a wind farm he helped fix or the photographs he took or the grid he helped make possible, perhaps as the first of more to come, Levine will have helped.

Even if he doesn’t know the people whose lives he benefited, they’ll know Joseph Levine. Gerlaugh and Team Afghan Power named the microgrid after him.

This article was written in June 2021, before the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan. Read an update on Levine and Team Afghan Power.