In 2004, GM Theo Epstein used those tactics to help the Boston Red Sox, still mired in the 86-year “Curse of the Bambino” for trading Babe Ruth, win a title. Then, years later, he did it again with the Chicago Cubs, ending a 108-year World Series drought. Analytics, it seemed, could expel even the sport’s worst demons. After almost two centuries, baseball had finally found its truth.

A Pastime Past Its Time?

But many in the baseball faithful haven’t been fans of the new style.

Plumeri came to William & Mary with baseball in his family and an instinctive love for the game’s traditions. His grandfather emigrated from Sicily in the early 1900s and wanted to integrate into American culture. And in 1927, the best way to do that was through baseball. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig would hit over 50 home runs each that year en route to a World Series, and Plumeri’s grandfather waited outside Yankee Stadium one day to convince them to host a barnstorming tour — or set of small-town exhibition games — around the state. There’s a picture of the three of them standing together at a train station.

“Baseball’s part of my family legacy,” says Plumeri, a longtime friend of Jackie Robinson’s widow, Rachel, and director of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, a scholarship program for minority college students.

Plumeri took that legacy with him to Williamsburg, playing second base for a team that had little more than the fundamentals. Their field was then squeezed behind Zable Stadium, with stands that held only about 50 people and had no fence around the outfield. If the ball rolled down the hill, it rolled down the hill.

When he donated the money to build Plumeri Park in the late 1990s, he wanted it to embody the cultural power of baseball so important to his family. They could’ve called it a “stadium,” but he chose “park” because it made games feel like an event, a day for hot dogs, pretzels, summer weather and people you love. Plumeri Park is named for his father, Samuel Plumeri Sr., who originally founded the Trenton Thunder in 1994. There’s a memorial to him outside, and when Plumeri visits campus, he tries to tell the team why that memorial matters.

“When you are on this field it’s expected that you’re going to do your best because the person this park was named after was special,” Plumeri says.

Hence, to him, gameplay based on big data feels robotic. Efficient baseball isn’t necessarily entertaining baseball. “If you remove the passion and you remove the commitment and you remove the drama from the game, you remove a lot of life,” Plumeri says. “Human error is supposed to be part of the game.”

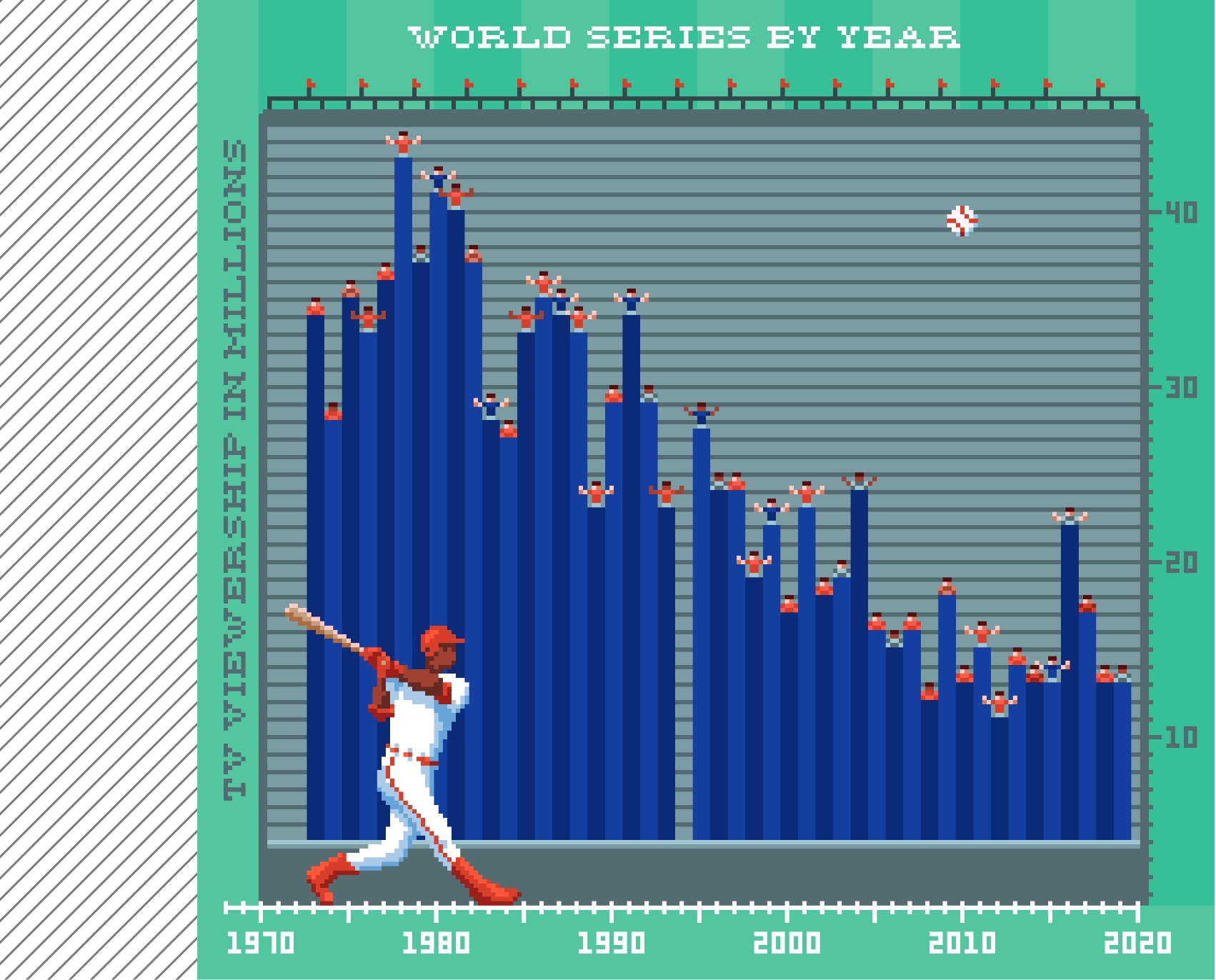

Many viewers agree. In 2000, the World Series attracted 18 million viewers. In 2019, that number fell to 13.9 million, with ratings down by almost a third. Last season, MLB set a record for the longest average game time, at 3 hours and 11 minutes, and the league batting average sank to a 53-year low. There were more strikeouts (April 2021 was the first month ever with over 1,000), more pitchers slowly entering and exiting games, and more empty minutes between balls in play.

“It’s just harder to engage fans on a broad scale than it was years ago as America’s pastime,” says Harris, the former Tampa Bay shortstop and now director of MLB athlete development at X10 Capital.

It’s not like baseball doesn’t have talent, he adds. There’s a generation of young stars — from the Washington Nationals’ Juan Soto to the San Diego Padres’ Fernando Tatis Jr. — playing at historically high levels. But great players don’t always make a great product, particularly when pitchers are better than ever. More strikeouts mean fewer runs scored.

Even more, MLB isn’t marketing its talent effectively, Harris says — a disconnect clear in the lockout this season. The league and the players’ association couldn’t agree to a new set of collective bargaining rules in time, the season started late, missed games cost everyone revenue, and fans lost time to watch the sport they love.

“Baseball has changed,” Plumeri says. “I don’t think it’s authentic like it used to be.”

"Moneyball changed a lot of things, where you realized that if you didn't have a baseball playing background but were analytically inclined, you could still make a career."

Baseball's Rocket Science

This crisis of authenticity has created a league-wide search for identity. Perhaps more than ever, baseball contains multitudes — from the purists who prioritize tradition to the Moneyballers snooping for the next competitive inefficiency.

It’s easy to see that incongruence in practice. Over the last 20 years, an enormous amount of baseball’s gameplay has changed, but the way people experience it hasn’t. Ballparks, telecasts and traditions like the allstar game are almost all the same. What happens behind the scenes, though, is radically different, down to the pitches batters learn to chase and the metrics taught to define success.

Will Rhymes ’05, director of player development for the Los Angeles Dodgers, spends his entire year operating backstage. After four years as an infielder for William & Mary, he began a 10-year career in the major and minor leagues, later retiring, joining the Dodgers as a scout and working his way up the front office.