A Bridge to the Quantum World

Zenith Tillemann-Dick ’23 leads a technology startup looking to reshape the field of quantum computing

October 17, 2025

By

Shannon Raymond ’27

In Norse mythology, Bifrost is a magical bridge that connects the cold mortal realm to the warmth of heaven. Zenith Tillemann-Dick ’23 envisions his startup company, Bifrost Electronics, in a similar way: “We see ourselves as that bridge — taking signals from the frigid, quantum-limited world and translating them into the brighter, more accessible world of classical mechanics.”

Tillemann-Dick explains quantum computing like this: “Quantum is the world of the ultra-cold, the ultra-quiet, the ultra-still and the ultra-small. When we’re talking about cold, we're talking about 100,000 times colder than the vacuum of space. When we’re talking about quiet, we're talking about a level of noise where the presence of light is deafening by comparison. We're talking about the point where all atomic matter stops moving. And when we're talking about small, we're talking about atomic-scale structures.”

Quantum computing enables highly complex information to be processed at speeds many times faster than today’s most efficient supercomputers. Use of this technology is expected to revolutionize a wide range of business and government operations – from strengthening cybersecurity and optimizing financial models to improving machine learning algorithms.

But for quantum signals to be read through traditional technology, amplifiers are needed. That’s where Bifrost Electronics comes in.

With current technology, the amplification process has been expensive and inefficient, Tillemann-Dick says.

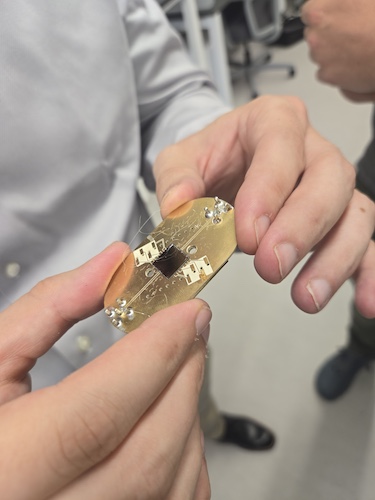

“Quantum amplification today requires a device that's about the size of a cinder block,” he says. “And you need about 100,000 of these devices for a utility-scale quantum computer — so, 100,000 cinder blocks. It's about the same size as the Empire State Building. It's not particularly functional. We built the same technology on a 10 millimeter chip. So, instead of needing the Empire State Building to hold amplifier devices for one quantum computer, you need the trunk of a Nissan Versa.”

Drawn to Startups

Tillemann-Dick’s passion for entrepreneurism was evident during his undergraduate career at William & Mary as an economics major. While on campus, he designed and built a social competition streaming app with classmate and friend Dominic Peterson ’21. “It was a fun project, even if it didn’t become a business,” he reflects. The COVID-19 pandemic derailed these plans, but not before the pair was able to run a pilot program on campus with about 20 friends and family members.

Later, he worked with the Johns Hopkins Technology Transfer group as a fellow at its Commercialization Academy. This office helps students and staff turn their scientific innovations into marketable products.

“That gave me a kind of deep vision into how startups actually work,” he says. “It’s not always just some guy with a brilliant idea who goes out and turns it into a company. Oftentimes, some guy with a problem goes out looking for a solution, finds that the technology has already been invented and isn’t being utilized effectively and goes to a tech transfer office and negotiates licensing deals, etc. And so that provoked this deep curiosity and excitement in startups.”

It was also during his time at William & Mary that Tillemann-Dick made his self-proclaimed best decision ever: marrying his wife, Lidia. The two had met at a coffee shop about three years prior. “That is the No. 1 decision, because having someone who supports you when you’re making crazy decisions and taking big risks is incredibly important,” he says.

After graduating from William & Mary, he distinguished himself at several up-and-coming health technology startups, rising through the ranks with his economic knowledge and background working in car sales prior to attending William & Mary.

“It's just been startups the whole way. Bigger fish, smaller pond every time,” he says.

Tillemann-Dick credits his brother Corban for introducing him to the quantum industry. Having started his own quantum infrastructure business a few years prior, Corban connected him with the engineers who became his Bifrost co-founders: Connor Denney and Logan Pauli. Denney and Pauli had recently made an exciting technological breakthrough and were wondering what to do with it next.

“A few years ago, my co-founders needed a traveling-wave parametric amplifier for a research project. Buying one would have cost $60,000 and taken eight months to deliver, so they built their own — and it turned out to be the best in the world,” he says. “That’s when I met them. The technology was already proven, and with my background in venture capital, tech transfer and company building, I saw the opportunity to turn it into a business.”

At their first meeting, he says, “It all clicked. We saw the organization, we saw the company, crystal clear. We had a half hour allotted on the calendar. I stayed there for three and a half hours with them.” That same night, he stepped away from his previous role and it was off to the races with Bifrost.

Bifrost’s technological breakthrough has attracted a flurry of investment interest in just its first few months of operation. In a recent seed funding round, Bifrost raised $4 million to support the next phases of development for its amplifier technology. Having started the company with just $56,000 in grant funding less than a year ago, Tillemann-Dick says Bifrost’s early success has been a dream come true. But it hasn’t come without a lot of hard work.

On top of being a co-founder of the Denver-based company, Tillemann-Dick has assumed the role of CEO, which comes with numerous responsibilities and challenges. “We started this company eight months ago, and I have not taken a weekend off,” he says. “I have probably slept two to five hours a night since that time, because there are so many problems, and there are so many questions every single day that only one person has the authority to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to.”

Even as he explains this, his excited smile never leaves his face. “Now, in that same breath, it is the most fun thing I’ve ever done in my entire life,” he adds. “I get to do so many things on any given day. One day, I will literally be assembling desks in our lab, because all of our engineers are doing science that I’m not capable of doing, and we need the desks assembled. And then the next day, I'm in a meeting with the undersecretary of defense for the United States. There’s just no middle ground.”

Room To Explore

Tillemann-Dick says his time at William & Mary helped to prepare him to take on this demanding and unpredictable career.

“The thing that I probably benefited the most from was interacting with the professors and getting comfortable with them one-on-one as peers,” he says. “So, now, I’m always the youngest person in every room that I go into, and I really don’t feel uncomfortable because I'm used to talking to brilliant people like they’re my friends.”

Economics professor John Parman taught his favorite course at William & Mary: American Economic Mobility.

“It completely reframed the way that I engage with society and culture and privilege,” Tillemann-Dick says. “The coursework that I did in that class genuinely did reshape the way I view the entire world, and it turned me into a much deeper patriot.”

Looking ahead, Tillemann-Dick envisions Bifrost as a key player in America’s growing quantum industry, particularly in the area of radio-frequency quantum sensing, which has various applications in communications, defense and other sectors.

“I see a lot of space for Bifrost to not just be America’s radio-frequency quantum company, but to truly be America's deep tech, radio-frequency house later down the road. And we're really excited about that roadmap,” he says. “Our goal is to build the radio-frequency technology that is vital to national interests. That includes quantum, but also includes components for radar, sensors, autonomous systems and the like.”

As a fairly recent graduate himself, Tillemann-Dick offers this advice for current William & Mary students: “Do stuff. Build stuff. Don’t sit around. Don't wait for someone else to give you an idea,” he says.

William & Mary has the resources for students to develop ideas, he adds. “We built an app while I was at William & Mary. We had all the technology that we needed, and all of the expertise that we needed. Find the smartest people around you, put your heads together, look at real problems in the world and see if you can solve them.”