Iron Men

January 8, 2019

By

Kelley Freund

In 1952 Jack Freeman ’44 and his wife, Jane, spent their entire life savings to move from Pennsylvania to Williamsburg so Freeman could be the new head football coach at William & Mary. It was a job few people wanted. In the summer of 1951, the athletic director, football and basketball coaches, and the school president had resigned.

Rene Henry ’54, who would become the sports information director as a senior in 1953, said the athletics program changed that year. “The desire from faculty was to deemphasize not only football, but all sports,” Henry said. “Scholarships were cut back by the time Jack Freeman was named head football coach.”

Then in January of 1952, 30 students were expelled for misconduct (eight of whom were football players). Nearly half of the remaining players transferred. “Some who played freshman football or as sophomores and lost scholarships after the athletic program changed in 1951 were frustrated and never walked on,” said Henry. “Some of those players would’ve been a tremendous help in 1953.”

Charlie Sumner ’55 was a sophomore on the 1953 team. “We had to play, no matter what. We couldn’t feel sorry for ourselves, because no one else was going to. When you’re cornered, you do the best with what you have. There’s no other choice.”

What they had was 14 returning lettermen and a total squad of 24, including John Risjord ’55, a track athlete who had never played football.

“I didn’t even know how to get in a three-point stance,” Risjord said. When he was knocked out during light contact drills, Freeman later told a reporter for the Richmond Times-Dispatch that he was knocked “stiffer than a board.” A teammate helped Rijord to his feet and said, “Welcome to varsity, Walk-on.”

Despite lacking in depth, the Indians found the small number of players assisted in the development of team chemistry. “We were all in it together,” said Sumner. “We knew what we could do.”

“We really cared for each other,” said Bill Marfizo ’56, a sophomore on the 1953 team. “No one was out for themselves. We had a sense of pride and wanted to do well because we loved William & Mary.”

And there were new NCAA rules that would work to William & Mary’s advantage. College football returned to the one-platoon rule, with athletes playing on both offense and defense. This off-set the lack of depth on the Indians’ team. With a smaller group, coaches were able to spend more time with athletes individually and players were able to adapt quickly to playing offense and defense. Freeman and his coaching staff shied away from hard contact practices, fearing injuries. “Hard contact was saved for the weekend,” said Marfizo. Practices were focused on conditioning each player to play 60 minutes of full-speed football.

Preseason forecasters had predicted only two wins for the Indians. But although they had a squad of just 24 players, as one opposing coach said, “They had 24 PLAYERS.”

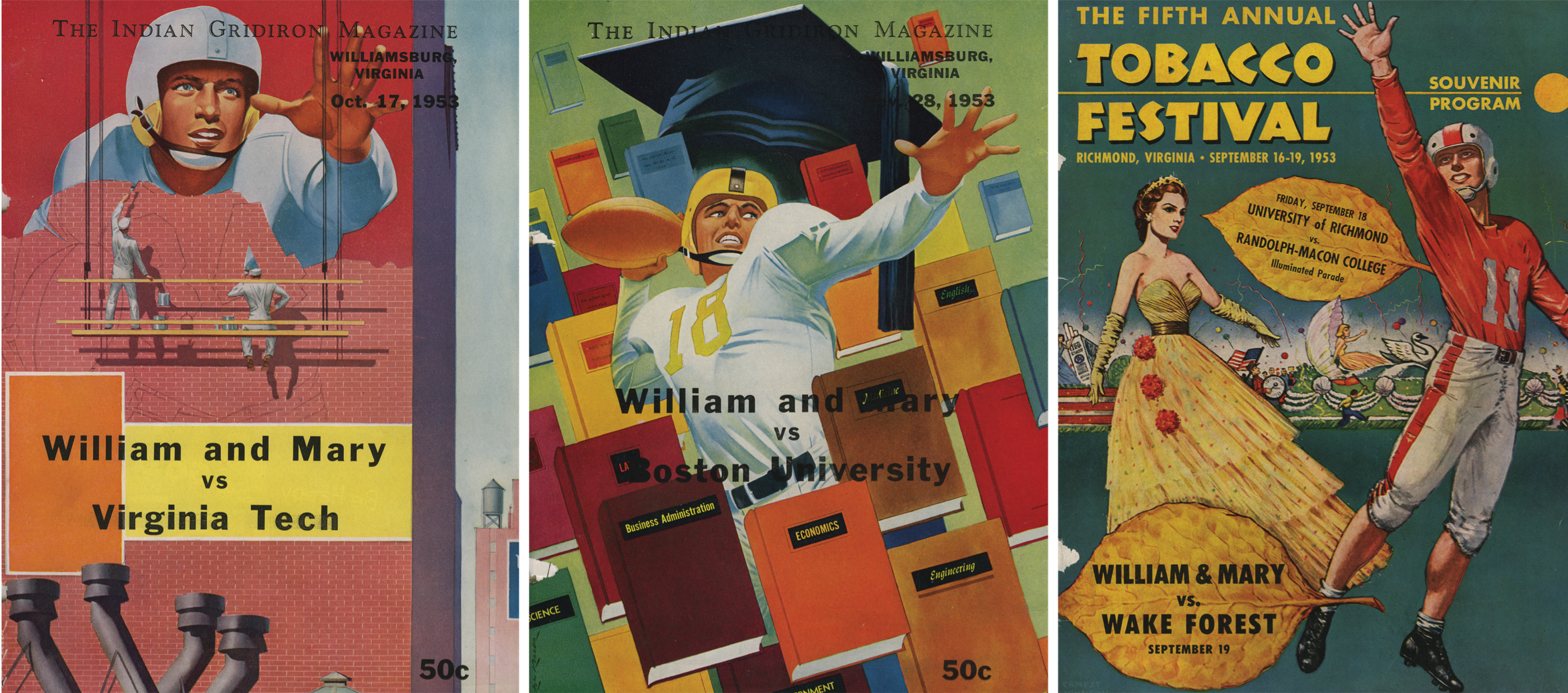

The Indians shocked everyone, going 5-1-1 in their first seven games. In their season-opener against Wake Forest, they snatched a third-quarter lead and made it stand up, beating the Demon Deacons 16-14. According to Flat Hat sportswriter Dick Rowlett ’56, Wake’s receivers were hit so hard that “at the finish they were watching the tacklers more than they were the ball.”

Going into the Navy game, the Indians were a two-touchdown underdog, facing a team that was ranked No. 1 in the East. Navy football greeted the visiting team with a, “Who’s he?” as each opposing player was introduced. After the game, the Middies were sure to remember at least one Indian player. Marfizo was dubbed Mr. Versatility by many Southern sports writers after playing seven different positions.

“First it was guard, then center, then linebacker and so on,” said Marfizo. “I remember Coach Freeman walking up and down the line and he kept saying, ‘Bill, can you do this?’” Marfizo also made a brave blocking attempt of Navy’s final punt that earned him a collision with a Navy player’s cleats and several lost teeth.

The Indians held in there with the Middies, deadlocking 6-6. It was after the Navy game that writers began calling the team the “Iron Indians.”

The Cincinnati Bearcats handed the team a loss that was the worst for an Indian 11 in 30 years, with a final score of 57-7, but an open weekend before the Virginia Tech game allowed the Indians the chance to recover and the “Upset Express” won their next three games.

“I think it was the underdog thing that kept us motivated,” said Marfizo. “It was a team spirit that I’ve never seen before.

When you’re down like that, you reach down deep and pull something up. And we were not only teammates, we were friends. When you go through things like that together, you form a bond.”

In the first seven games, 13 men played the entire 60 minutes without replacement. Three players did it three times apiece. In the game against Virginia Tech, Marfizo played a full three and a half quarters before being carried off the field unconscious from a blow to the neck.

But toward the end of the season the fighting two dozen began to show signs of hard-fought battles. Injuries took their toll and with no reserves, the Iron Indians began to buckle, losing three of their last four games. A VMI touchdown in the last 58 seconds gave the Indians their second loss of the season. The upset wrecked the Tribe’s bid for the Big Six crown, the Southern Coference Championship and a possible bowl bid. The Indians clobbered Richmond 21-0, but the following week the Generals from Washington and Lee turned the game into a rout in the span of eight minutes in the third quarter. Boston University, with a hard-charging line, explosive backfield and the most depth the Indians had seen all year, handed the Iron Indians their final loss of the season.

The Indians finished the year 5-4-1. Four players made the All-Big Six Team, the most from any one team. Jack Freeman was named coach of the year in Virginia. After the season the William & Mary community came out to honor the team at a special ceremony at Phi Beta Kappa Hall.

“I consider this team one of the most remarkable in modern football,” said Henry. “I doubt if any other coach would have taken the challenge Jack Freeman and the Iron Indians did in 1953.”

There was a moment during the game against Navy when kicker Quinby Hines missed booting extra points because of a poor pass from center and tried to take it across the goal line himself — all 137 pounds of him. It was just one of those moments the Indians refused to say die, just one of the countless instances during that 1953 season when William & Mary’s football team pushed the limits of human endurance. “It was a time we came together under difficult circumstances,” said Marfizo. “It made things very memorable. I’ve never felt a greater sense of pride.”