Amplifying Student Voices

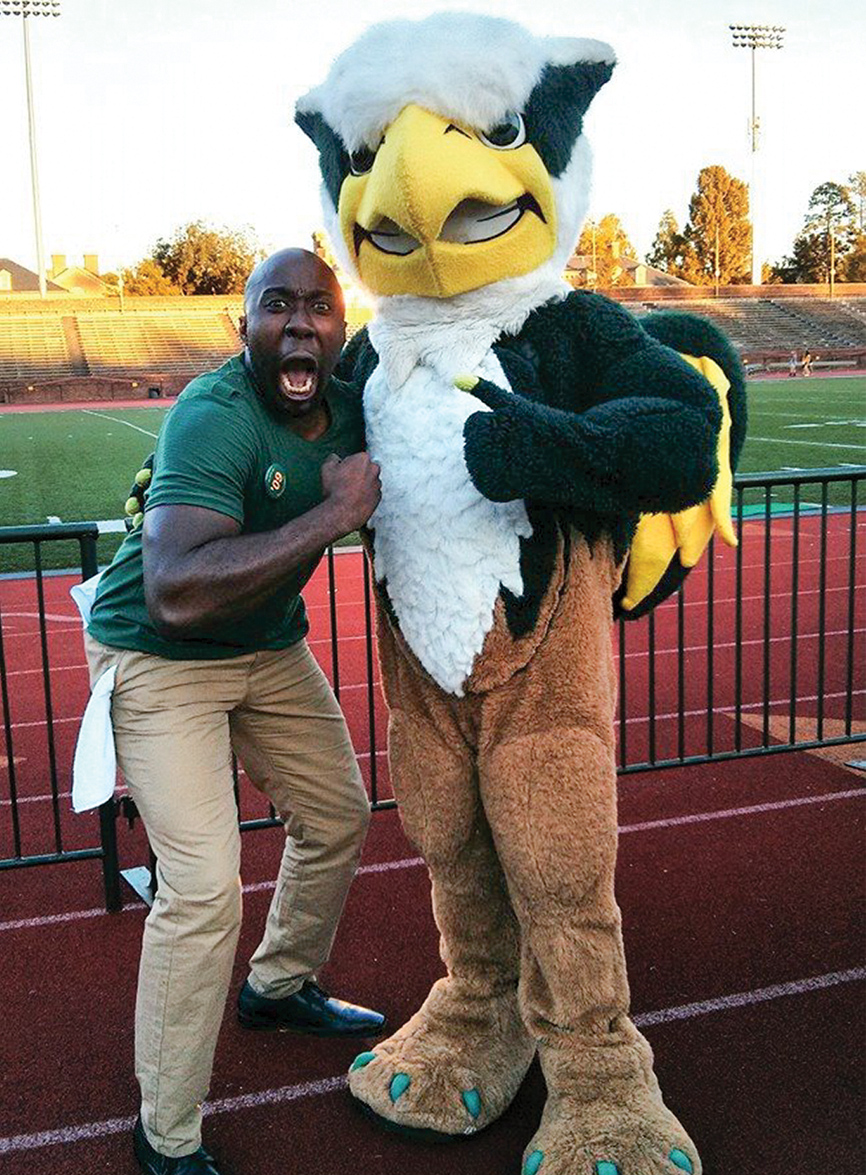

Kevin Dua ’09 is an award-winning teacher and advocate for his students

September 15, 2021

By

Claire De Lisle M.B.A. ’21

Kevin Dua’s students are leaders. World-changers. Role models. But the world doesn’t always see them that way.

“It’s a privilege seeing students engage with each other to better their environment. Folks who invalidate students’ self-worth because of their perceptions of those students’ age, grades or appearance miss out on the incredible sight of students being leaders in real time,” Dua says. “I try to earn students’ respect and curiosity as their teacher, and I try to earn their consent to be a cheerleader for their voices. We don’t give students voices — they always have it, and it’s a miseducation whenever we suggest they wait until post-graduation to use it.”

It’s this unfailing belief in his students and what they can achieve that has brought Dua recognition throughout his career. In 2017, he became the first Black educator to be awarded Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Massachusetts History Teacher of the Year. That same year, he was a finalist for National History Teacher of the Year. His work has been recognized by NPR, PBS, Learning for Justice, Abolitionist Teaching Network, UpLift Cohort of Black Male Educators and more.

In May, he was honored with the Comcast NBCUniversal Leadership Award. The award celebrates City Year alumni “who are continuing their commitment to strengthening community, inspiring, mobilizing and empowering others, creating and developing sustainable solutions for social change and who exemplify the core values of City Year,” which include service to cause greater than self, social justice for all, empathy and inclusivity, among others.

It was through City Year, an AmeriCorps program that places young graduates as student success coaches in systemically under-resourced schools, that Dua began his teaching career, but his passion for teaching history started at William & Mary.

He was originally a government major and wanted to become a lawyer. That changed when he met Jody Allen Ph.D. ’07, who would become his mentor, and who is now the director of the Lemon Project at William & Mary. Their conversations about the civil rights movement, Black identity, and the importance of educating others about history with a critical lens inspired him to switch his major to history.

“Allen was instrumental in making me aspire to be that Black history educator who takes pride in diversifying curriculum with lessons on people from American history like Tituba, Marsha P. Johnson, John Brown, Fred Korematsu and Elián González,” he says.

He applied to City Year, which placed Dua in Boston. There he had his first experience connecting with students in the classroom. He loved it, and he knew he wanted to learn more.

“City Year reaffirmed for me that being an educator calls for us to share with and learn from every student,” he says.

After City Year, Dua earned his master’s degree in secondary education at The Charles F. Donovan Urban Teaching Scholars program at Boston College. He then returned to the classroom, where he pairs teaching with encouraging students to be active participants in the life of their school. For example, students at Somerville High School, where he supervised the student government, campaigned for free tampon dispensers in bathrooms and changed the royalty titles for their prom court to be inclusive of LGBTQ+ students. And students at Cambridge Rindge and Latin, where he supervised the Black Student Union, led volunteer projects and social justice forums with classmates, teachers, Congressperson Ayanna Pressley and author and activist Cornel West.

He says his students are his best evaluators, and that he hopes they consider him as someone who doesn’t shy away from difficult topics — and as someone who is genuinely interested in their lives.

Dua is one of just 7% of U.S. public school teachers who are Black and 1.7% who are Black men, and Black educators are more likely to exit the profession or change schools, according to the Learning Policy Institute. In 2018, as a member of the first all-teacher Boston Marathon team, Dua advocated for increasing the number of teachers of color. In 2019, he partnered with City Year and Boston College to set up a scholarship for City Year alumni pursuing an M.Ed.

He travels throughout the country, presenting and consulting on anti-racism and anti-bias for academic conferences, nonprofits, and schools at all levels. He continues to mentor first-year AmeriCorps members and conducts workshops on supporting students’ civic engagement.

“As Black educators, we face racism from white peers; for years, I’ve listened to countless Black teachers across the nation who’ve shared their struggles with me,” says Dua. “To support teachers of color, K-12 schools and universities like W&M must openly and consistently acknowledge their own complicity and complacency in invalidating their Black educators.”

Despite the challenges, he is inspired to keep teaching through his faith and the support of his spouse, Rebekah, family and friends, mentors and students — as well as those who came before him.

“There are individuals whom I’ve never met that contributed to the opportunity for me to attend college and feel unapologetic in my melanin,” he says.

“Whenever students of color ask me if they would fit in at William & Mary, I don’t name-drop alumnus Thomas Jefferson or Jon Stewart ’84, D.A. ’04; I mention Janet Brown Strafer ’71, M.Ed. ’77, D.Sc. ’18, Karen Ely ’71, D.Sc. ’18 and Lynn Briley ’71, D.Sc. ’18 and their time as the first Black residential students. I mention Crystal Joseph ’09, a Black licensed clinical professional counselor and founder of PsycYourMind, and Lamar Shambley ’10, a Black teacher and founder and executive director at Teens of Color Abroad, who are — among many others — good people doing good for people today.

“I want my students to see themselves in any space, just as Congressperson John Lewis’ remarks at my freshman Convocation and Allen’s classes did for me. Whether it was as a City Year member or a history teacher, I don’t take lightly or for granted how fortunate I am to do what I love.”

Kevin Dua ’09 wrote the fall 2017 W&M Alumni Magazine cover story “Black at William & Mary,” in commemoration of 50 years of African American students in residence.