A Journey of Reckoning and Discovery

Witney Schneidman’s path to establishing the Lemon Scholarship Endowment

May 23, 2022

By

Jacob A. Miller ’18

In April 2019, Witney Schneidman made the long walk from the entrance of Swem Library to Special Collections with a pit in his stomach.

What am I going to find? he thought.

He asked to see the ledger of his ancestor, Samuel Francis Bright. The aging books were brought to him with care by the Special Collections curator.

On those pages, he found that his ancestor, Samuel Bright, had owned enslaved people on the William & Mary property where he sat. This discovery sent him on a path that eventually led to establishing a scholarship for descendants of the enslaved.

The Lemon Scholarship will provide need-based scholarship support for students who are descendants of enslaved persons in the U.S., or who have a demonstrated historic connection to slavery. Preference will be given to those with direct lineage to enslaved individuals who labored on former and current grounds and property controlled by W&M, including the Bright family farm. The scholarship is named for Lemon, a man who was once enslaved by William & Mary and who represents the many known and unknown African Americans who helped to build, maintain and move the university forward.

PAGES OF NAMES, PAGES OF NUMBERS

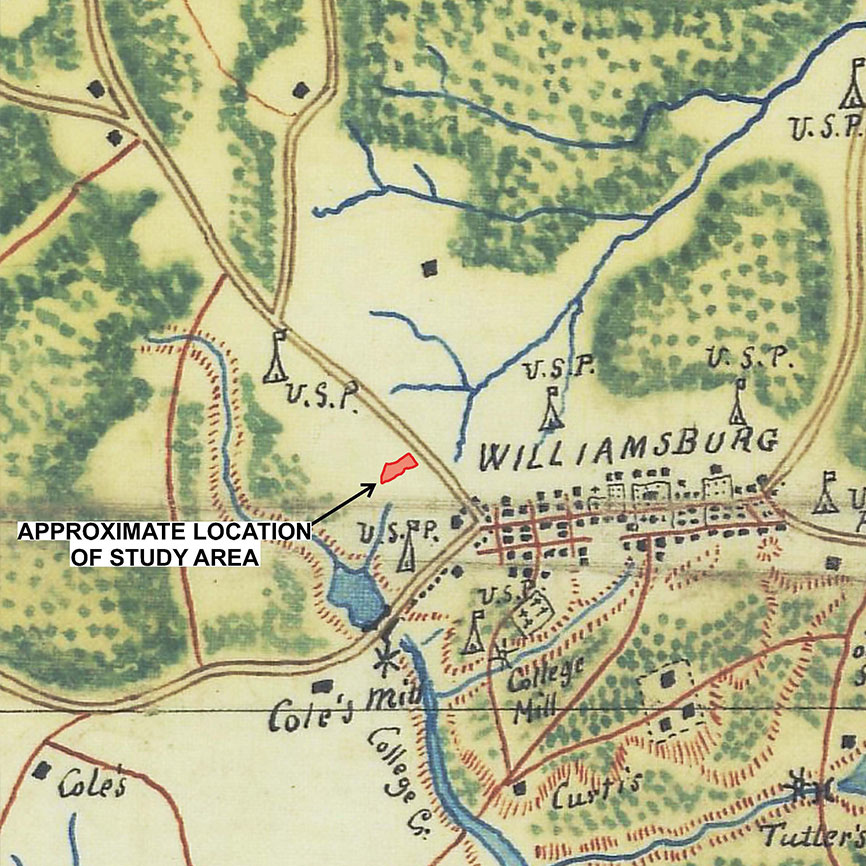

While the Bright House is today best known as the historic portion of the W&M Alumni House, the Bright family has a long history with William & Mary. In approximately 1839, Samuel Bright bought a nearly 600-acre tract of land immediately to the west of William & Mary’s property. The farm was called “New Hope,” and it was used by Samuel to supplement the work done at his other property on the east side of town, Porto Bello.

“There’s a lot of people in the records,” says Sarah Thomas ’08, M.A. ’12, Ph.D. ’18, associate director of the Lemon Project at William & Mary, a multifaceted and dynamic attempt to rectify wrongs perpetrated against African Americans by William & Mary through action or inaction. “For example, in 1850, there were 14 enslaved individuals on Samuel Bright’s properties, and there are ages of the enslaved listed in the records as well.” In 1852, 44 slaves were present on the New Hope farm.

According to Thomas, the people the Brights enslaved at New Hope may have performed leased labor for the university to help with woodcutting and other tasks, because the Bright property was close to the campus.

After the Civil War, Samuel Bright’s son, Robert, inherited the lands owned by his father, including New Hope. In approximately 1871, he built a large brick house on the property, as evidenced by tax records. After the house was passed down through the family, it was sold to William & Mary in 1946 and would become the Alumni House in the decades that followed.

As Schneidman sat reading the account books of his ancestor, he was struck by the gravity of what he was reading.

“Just to see the names, it was so powerful: ‘Mary Jane, 16 years old, slave worker called Washington, slave worker called Daniel, Amy, Anne,’ the list went on. There were no African names there. What does that say? People had just been ripped from their origins, from their identity, from their families, from their history. It was right there in black and white.”

He left Swem in a mix of emotions, but one thing became certain in the weeks and months that followed. “I asked myself, ‘what are you going to do about it?’”

BRIDGE TO THE PAST

Schneidman is the senior policy advisor and head of the Africa practice for Covington & Burling LLP. He has had a sweeping 50-year career connected to Africa.

After graduating from boarding school in Massachusetts, he took a year off to travel to Israel and Europe in the early 1970s. His journey took a detour to Africa after meeting fellow travelers from the continent. This detour would prove to be life changing.

While in Uganda, military dictator Idi Amin executed a coup d’état, which Schneidman heard announced over the radio by Amin himself. This was a transformative experience for him and awakened him to the world as it was, he says, not the world he had known in the United States.

“From the time I first visited Africa between high school and college, I knew what I wanted to do in my career — I wanted to be a bridge of understanding between the United States and Africa, and maybe one day I could help shape U.S. policy toward Africa,” says Schneidman. He later served as deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs under President Clinton, as a member of the Africa advisory committees in the Office of the

U.S. Trade Representative and at the U.S. ExportImport Bank. He also co-chaired the Africa Experts Group on Barack Obama’s campaign for the presidency and was on the Presidential Transition team. In recent years, he decided to write his memoir in hopes of inspiring young people to become more involved in entrepreneurship and economic development on the continent, as he himself was inspired 50 years ago.

“One of the touchstones for me was to write the fullness and the truths of my experience — and that led me to my family’s story,” he says.

He grew up knowing that his great-grandmother, Nannie, came from Williamsburg. A century later, in 2003, Schneidman and his mother came to Swem Special Collections for the first time to see correspondence of Nannie Bright. Several years ago, though, Schneidman began to think there was more to the story that he was missing. He was curious as to whether or not the ancestors he knew little about, well-to-do farmers in the 1800s, might have owned slaves.

“I emailed the librarian at Swem and asked if maybe there were enslaved workers on the Bright farm? And they told me, ‘Without a doubt.’ They invited me to come look at the documents they had,” he says.

FROM RECKONING TO ACTION

Over the next year, he told his family about what he learned to prevent, what he called, “another generation of silence on this.”

“They cared about what I had discovered, and we came together as a group to do something bigger than all of us,” he says.

In December 2020, Schneidman reached out to staff at the Lemon Project to learn more about the Brights and to discover ways he could give back. He wanted to, in some way, attempt to rectify the actions of his forebears and promote racial reconciliation.

Then, in May 2021, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam signed a bill requiring five Virginia universities that benefited from and exploited slave labor, including W&M, to establish scholarships and programs specifically for descendants of the enslaved.

“When that happened, that proved to me that we are not alone as a family fighting to redress systemic racism,” Schneidman says. “There are people who care about this and are willing to invest of themselves.”

Schneidman, his sisters Liddy Lindsay and Margot Brownell, his son Sam and his niece Lela Beem have established the Lemon Scholarship Endowment as one of the scholarship funds consistent with the 2021 legislation, the second endowment of its kind at W&M. The first scholarship endowment for descendants of the enslaved was created in memory of the late Anne R. Willis, the wife of long-time W&M faculty member Dr. John H. Willis, Jr., by her children in early 2021.

Schneidman knows there is still work to be done. He says his research showed him that history lives on in all of us today, in the stories we tell and the way we tell them. For Witney Schneidman and his family, engaging with that history is one way to ensure there is a generation of action, not silence. “I hope this scholarship enables students to be able to realize their dreams, whatever those are, and that they will be equipped with the skill and knowledge to be the very best that they can be,” he says.

“Each of us in our own way has a role to play in this. That’s part of the challenge, to figure out what our role is and how can we contribute to make our country live up to its full value and potential.”