What do beavers in Argentina have to do with river herring in Virginia? Anthropology Assistant Professor Mara Dicenta believes both can help us understand the long-term effects of colonialism on the environment.

Before coming to Williamsburg in fall 2021, Dicenta conducted ethnographic fieldwork related to beavers in Tierra del Fuego in Patagonia, Argentina. The Argentine government introduced Canadian beavers to Tierra del Fuego in 1946 to encourage a fur trade that could help modernize the region and attract more residents. Without predators, the species expanded and has severely damaged native ecosystems.

She is planning to work in Virginia with scientists and Indigenous communities, starting with a project to restore river herring and bring to light traditional ecological knowledge. According to William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science, river herring populations have been in dramatic decline since the 1970s due to habitat loss, overfishing and pollution.

“I see many parallels between my research in Tierra del Fuego and my research here,” Dicenta says. “If you think about it in terms of the environment, both areas have been marked by water. Here we have huge rivers which flow into the sea. Tierra del Fuego is surrounded by the ocean.”

Both places also have ties to colonialism.

“Tierra del Fuego became an international trade port,” Dicenta says. “Here, we have Jamestown and Williamsburg as key Colonial enterprises. Colonial commerce marked the histories of those who lived in these lands and waters before.”

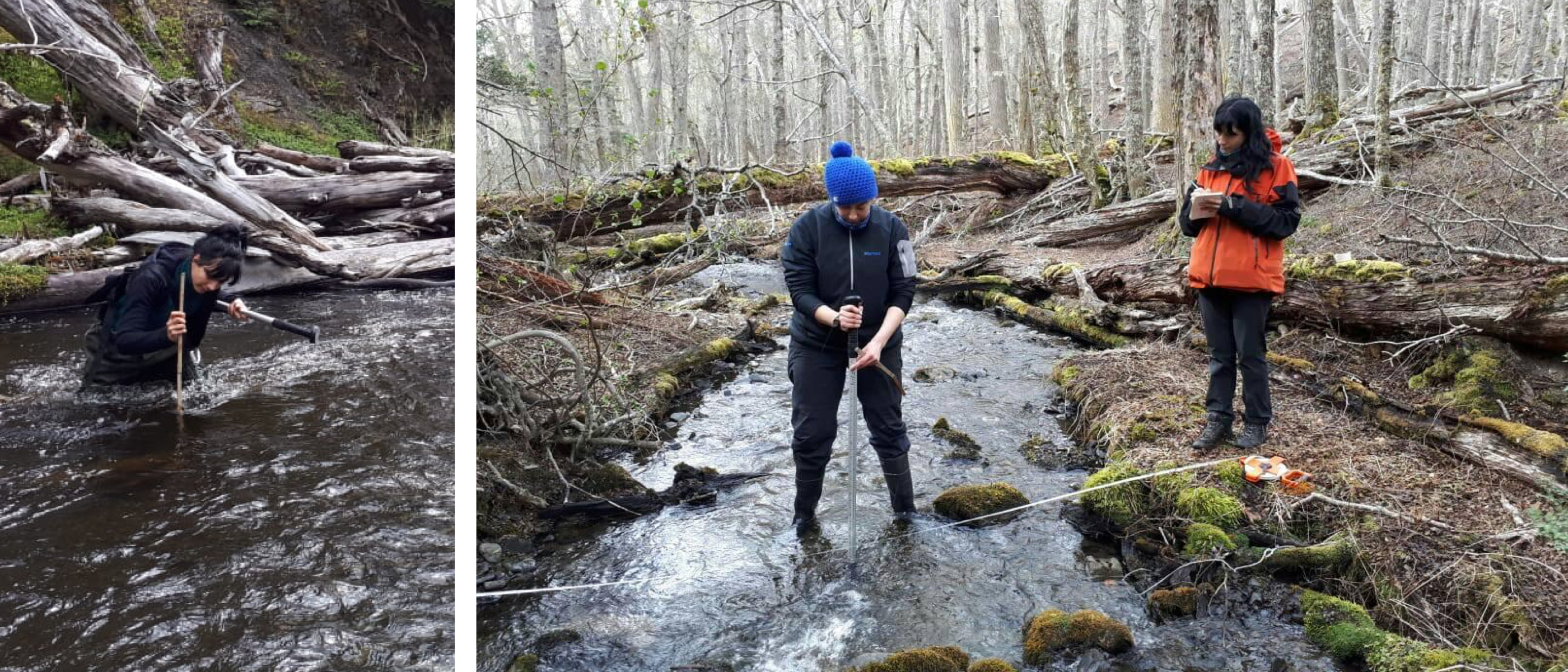

In Virginia, Dicenta is beginning to work in collaboration with the Rappahannock Tribe and the Smithsonian Institution on the restoration of river herring, integrating the tribe’s oral histories and current practices regarding rivers, aquatic life and fishing. In Tierra del Fuego, Dicenta is working with Indigenous communities to guarantee their right to be consulted before implementing conservation projects.

Undergraduate students will be involved in her research through the Conservation Research Program housed in William & Mary’s new Institute for Integrative Conservation (IIC). The IIC opened in 2020 with the mission of research and education to help solve the world’s most pressing conservation challenges.

“In just a few years, the Institute has created so much. The staff at the IIC come from all different backgrounds, but we all come together to collaborate,” says Dicenta.

John Swaddle, the IIC’s faculty director, says the addition of Dicenta and faculty member Fernando Galeana-Rodriguez has allowed the Institute to launch its new integrative conservation minor. A dozen students have expressed interest in the new minor so far, while about 10 students are expected to declare self-designed conservation majors.

“Mara and Fernando both have years of experience working with Indigenous communities on conservation solutions framed in environmental justice,” Swaddle says. “As emerging leaders in their fields, Mara in anthropology and Fernando in sociology, they are already helping students learn about the crucial connections between people and nature.”

Dicenta, who has Spanish and Argentine heritage, became interested in anthropology in 2007 while she was taking a course on gender and sexuality.

“In this course, I learned that the idea that we have two genders is not the way the rest of the world thinks about things,” she says. “I learned about cultures that had three genders, five genders. It shocked me. I discovered that everything I had assumed could be questioned and I decided then to pursue a B.A. and two master’s degrees in anthropology.” After that, she completed a doctorate in social studies of science.