Joyce Hill Stoner ’68 is many things: an eminent art conservator, a teacher, a playwright, an author, a historian, a mentor, a friend to many. She’s the foremost expert on the techniques of late American painter Andrew Wyeth. She’s got a way of telling stories that makes them dramatic and funny, no matter the subject.

The Many Sides of Joyce Hill Stoner '68

An eminent art conservator shares her story

June 4, 2024

By

Claire De Lisle M.B.A. ’21

Photography By

Michael Miville

Stoner has worked on art from the Smithsonian Institution to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the Winterthur Museum. She has touched the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, interviewed the who’s who of the art conservation world and written the definitive textbook on restoring paintings. She is now a named professor and director of the Preservation Studies Doctoral Program at the University of Delaware and an instructor and paintings conservator in UD’s joint program with Winterthur.

She calls herself both a conservator and a restorer. She notes that elsewhere in the world, art conservators are called restorers, and curators (those who manage collections) are called conservators. “Restorers can sometimes be seen as hacks without training here in the U.S., but I use the terms interchangeably because I’ve worked with so many people from other countries,” says Stoner.

“Just don’t call us conservationists,” she adds, laughing. “Those are the ones protecting fish and wildlife.”

Conservators clean, preserve and repair works of art. Stoner describes art conservation as a “three-legged stool” that requires science, art history and studio skills.

The description was coined by George L. Stout, considered one of the founders of art conservation, with whom Stoner worked.

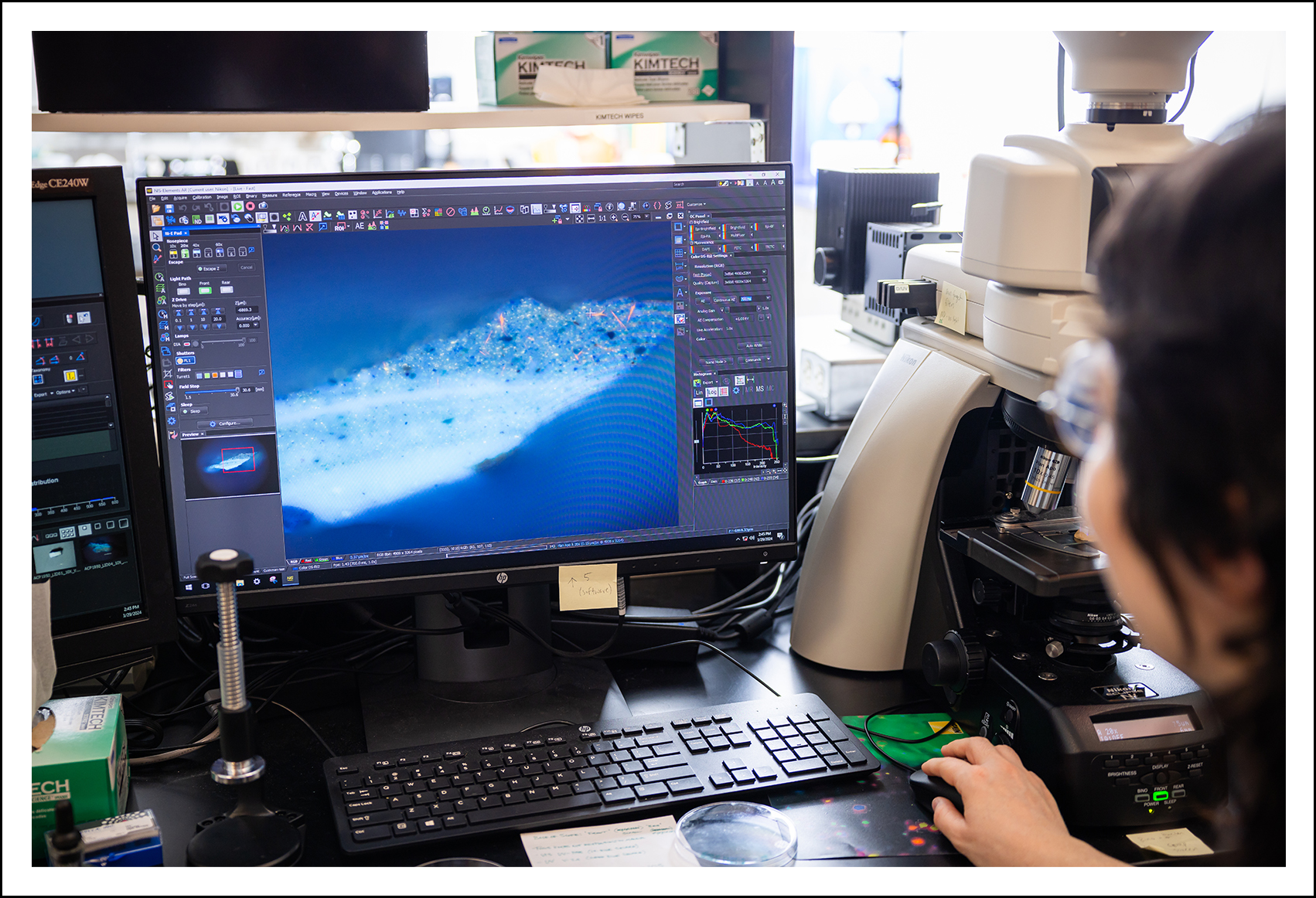

Science includes chemistry (knowing which solvents will dissolve which varnishes or analyzing pigments under a microscope to determine their composition, for example) as well as physics (understanding thermodynamics and light refraction, for example) and materials science (how different materials behave under stress).

Art history can encompass archeology, material culture (how people use objects) and library science, depending on the type of art you might conserve and its age.

Fine art studio techniques allow the conservator to create a repair that is seamless with the art around it — replicating original brushstrokes on a painting or sculpting a realistic replacement toe for a statue.

When Stoner began teaching in this field, she thought the fine art skills were the most crucial and couldn’t be taught. Working with students has since shown her that the most important elements are patience, attention to detail and a passion for the work. You can learn the studio skills.

“You must love the art,” she says. “You will train for as long as a doctor, but not make the money they do.”

Being a strong problem-solver is also important.

“I love every day because it’s never the same — always a new challenge. But that wears some people down,” she says. “I had a student who always wanted the one ‘right’ answer. He’d ask, ‘Should I use this technique on this painting?’ I’d always answer, ‘It depends. What are you trying to achieve?’ He left conservation and went into dentistry.”

The Student

Stoner’s dream as a student was to work in theatre. Her father was a newspaper editor who told her she could study anything as long as she learned typing and public speaking. Her mother and sister had gone to the women’s college Mount Holyoke in Massachusetts, but Stoner was interested in “not having an all-girls cast,” she laughs.

On the way from their home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, to visit Duke University in North Carolina, the Hill family stopped at William & Mary — and never made it to Duke. After seeing William & Mary’s campus and Colonial Williamsburg, then hearing about longtime theatre professor Howard M. Scammon Jr. ’34, she was hooked.

She filled her need for the stage with performances in W&M Theatre productions of “Kiss Me, Kate,” “Damn Yankees,” “Carnival” and other productions. With the Backdrop Club, she and the late Bill Brooke ’68 wrote the music and lyrics for “Stop 13,” a musical named for the number of the Colonial Williamsburg stop on the W&M bus route.

It was because of a workshop production of “Hamlet” that Stoner met her future husband, Patrick Stoner ’69. Patrick played the title role while Joyce played Ophelia — and Joyce’s boyfriend at the time was the director. When the boyfriend went off to the Navy, Joyce and Patrick began dating. They were married in the Wren Chapel in 1970.

Patrick, who was a theatre major at W&M, went on to a career in public broadcasting. He is a well-known film critic for WHYY, the PBS syndicate in Philadelphia, and has interviewed actors from such as Tom Hanks and recent Oscar winner Da’Vine Joy Randolph.

She remembers that during the pandemic, when Patrick couldn’t travel for interviews, “My daughters and I would be talking in the living room, and William Shatner’s voice would just come out of nowhere — Patrick would be on a Zoom with him in the family room!”

Unlike Patrick, Joyce Hill Stoner became a fine arts major, following another of her passions, on the reasoning that theatre could always be part of her life outside her career.

Thomas Thorne, one of her favorite professors, showed her class a series of paintings he had done of the old Williamsburg mill in the style of Renoir, Cezanne and Monet.

“I saw that and I said, ‘I wanna paint 22 self-portraits in the style of the Old Masters from cave painting to pop art.’ If you can imagine the chutzpah of me as a junior! And he said, ‘It sounds like you want to go into art conservation’. And I said, ‘What is that?’”

Thorne, as well as fine arts professor and art historian Carl Roseberg and chemistry professor William G. Guy D.Sc. ’69, helped encourage her toward the field and acquire the skills she needed.

She did end up making those 22 self-portraits and most of them survive today. Stoner uses them in her classes at Winterthur for experimenting with different cleaning and repair techniques. “They became sacrificial,” she laughs.

In her senior year while on a pre-program internship at the Smithsonian, she met visiting expert Rostislav Hlopoff, a renowned objects conservator who worked for major collectors and the Frick Collection in New York City. He told her to smash a flowerpot and put it back together to develop Fingerspitzengefühl – in German, “fingertips feeling” — the feeling of a smooth seam, a perfect join. It’s a feeling she still uses in her work to this day, especially filling in losses in paintings.

“So back on campus, I put my little flowerpot in a bag, and was going to smash it in there, and Mr. Roseberg said, ‘No, no!’ And he threw it — WHAM — against the wall like he was bowling! So I picked up all the little pieces and put them in a sandbox and got to work,” she says.

“I remember a football player came over to me and joked, ‘Wouldn’t it be easier to get a new one?’”

The next year she was accepted into the only graduate program in the nation for conservation, at New York University. It had been founded in 1960, and it only admitted two men and two women per year. William & Mary previously had sent Ben Johnson ’60 and Jim Greaves ’65 (both of whom remained in the field and later worked at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), so “William & Mary was uniquely informed about art conservation — which was certainly not true of, I would say, 95% of all the other universities in the U.S.,” says Stoner.

She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in fine arts, summa cum laude, and was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa for her accomplishments. With her degree in hand, she headed to NYU to learn to become a conservator.

Today at William & Mary, interested students are encouraged to explore conservation as a career option as well.

“The few graduate programs in art conservation recommend that applicants take substantial undergraduate coursework in art history, studio art and chemistry. My department is taking steps to help our students prepare for graduate study to lay the foundation for a professional career,” says Alan Braddock, chair of the Department of Art & Art History and the Ralph H. Wark Professor of Art History, Environmental Humanities and American Studies.

On April 1, an eminent art conservator from Durham University in the U.K., Emily Williams, visited Cristina Stancioiu’s art history class on cultural heritage to discuss her work. In the fall, the art history department plans to host a public forum with conservators on current issues in art conservation and how undergraduates can best prepare for graduate study in the field. These events coincide with William & Mary’s Year of the Arts, which runs through Dec. 31, 2024.

Several W&M faculty have experience on the chemistry side of art conservation. Tyler Meldrum, associate professor of chemistry and director of undergraduate research, has studied with his students the chemical properties of paint in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, and his research includes understanding material properties and chemical processes in conservation treatments. Kristin Wustholz, professor of chemistry, has worked in collaboration with the paintings conservation lab at Colonial Williamsburg and the Philadelphia Museum of Art to use surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy to identify pigments in works of art.

William & Mary students also go into internships and other programs to explore this career track. Lorelei Peterson ’25 will be attending the San Gemini Preservation Studies field school in Italy this summer. She’s an art conservation major in the critical curatorial studies track.

When Braddock told her about the program, she was excited to attend to get hands-on experience in preservation work: “I love studying art and I also want to make it into a career. This can show me how people decide what to restore and how to restore it and how different departments of museums work together, beyond what we learn in class.”

The Oral Historian

Stoner went into conservation at a key time for the field. The 1966 flood of the Arno River in Florence, Italy, had made global news for its impact — the waters damaged or destroyed millions of works of art and priceless manuscripts. Volunteers called the “mud angels” came from all over the world to assist in cleanup and restoration. Their efforts led to new protocols in conservation and increased interest in and funding for cultural preservation worldwide.

But 40 years before, a quieter renaissance of art conservation had upended the trade. In the 1920s, as Egyptomania overtook the U.S. after the discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb, art conservation came into the public eye in new ways. With new use of chemistry and x-rays, it made a shift to “serious pursuit” from what Stoner describes as an “apprentice-trained secret society.”

In 1928, the first research laboratory in an American museum opened at Harvard’s Fogg Museum (the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Louvre in Paris opened theirs three years later). The two men often referred to as the fathers of modern art conservation worked together there: Rutherford John Gettens as chemist and George L. Stout as head conservator. (In a nod to her love of theatre, Stoner refers to them as the “G&S [Gilbert and Sullivan] of conservation.”)

In 1974, Gettens spoke at the American Institute for Conservation meetings in Cooperstown, New York, and urged those present to begin “collecting material for a history of the conservation of cultural property.” He felt it was important to record personal anecdotes of working on art and the personal stories that informed the official records. Upon leaving the conference, he began writing his own personal history — an effort that was cut short by his death 10 days later.

Stout was aware that Stoner served as managing editor of NYU’s Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts journal as well as the conservation department’s librarian. He asked her to carry out Gettens’ idea.

Thus, the Oral History Project was born in 1975, led by Stoner and sponsored by the American Institute for Conservation and the Foundation for Advancement in Conservation. There are now more than 500 interviews in the archive, conducted by more than 100 conservators and students.

“Artists are interviewed all the time. But conservators — they were not popular in the eighth grade. They were the observant types, not the cheerleaders or football players. Some don’t want to be interviewed, but mostly they are delighted someone is interested in their career, who trained them and why they do a particular treatment. And we create these connections between people,” she says.

Through this project, the one-time “secret society” of art conservators has now made their work and experiences public.

“Conservation used to be, when I started at NYU, a quiet thing that you didn't tell people about. You just did it,” says Stoner. “And now it’s everywhere. Museums all have blogs and YouTube videos about it. The public is interested. We have two or three tours a week at Winterthur about conservation, whereas we didn’t have any at NYU — aside from Jackie Kennedy one time.”

The Teacher

Once Stoner finished her studies at NYU, she and Patrick stayed in New York City while Stoner took on a series of internships and contract assignments treating paintings.

Then, suddenly, Virginia Commonwealth University reached out to her (“How did they even know about me?” she wonders) and asked her to substitute for someone on sabbatical. She was to teach a pre-graduate conservation class, designed to help undergraduates get the science, art history and hand skills needed to apply to graduate programs.

“I had no desire to teach, particularly. I had decided I would work at the Met and treat wonderful Old Masters,” says Stoner, referring to the art of well-known European painters. “But I love it. I like to say I’m a vampire, feeding off the students to keep me young and energetic.”

In 1974, the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation opened, just the third graduate program in the nation (it is still only one of five). Stoner left VCU to become a professor there in 1976, spending half her time teaching and half her time working on Winterthur’s paintings — in particular the works of 18th-century painter Charles Willson Peale.

She continued a program she had begun at VCU, a clinic where members of the public could bring their art and have the students advise them on what care the art needed. The clinic still runs six times a year at Winterthur.

By 1982, though, the National Endowment for the Arts funding the program relied upon — funding that had been inspired by the devastating flood in Florence — had ended.

“I was called into the dean’s office at the University of Delaware, eight months pregnant, and told, ‘We’d like you to become director, but the program will close unless you raise an endowment.’”

And so she did, raising $6 million — at one point hiding her new baby in a bouncer behind a door so she could give a major donor a tour (the donor, upon hearing about baby Eliza, asked to look behind the door to meet her).

At that time, a master’s was the terminal degree for conservators. When a new president arrived at UD in 1987 and challenged each of the university’s departments to think big and come to him with visionary ideas, Stoner asked about founding a Ph.D. program in art conservation

“Otherwise, curators will always have Ph.D.s, and we won’t, and we will be paid less and have less attention paid to us,” says Stoner.

The president and faculty senates approved the program. Stoner became the director in 2005, a position she holds to this day.

Stoner describes the layers of conservation education like this: The undergraduate pre-conservation program is like pre-med. Then there’s a master’s program, training the doctors and surgeons who do the day-to-day medical work. A Ph.D. program is like the cancer researchers. They become experts on particular artists, techniques, philosophies and changes in the field, and publish their findings.

But to run a Ph.D. program, Stoner felt she should have a Ph.D. herself.

She chose as her subject James McNeill Whistler, whose “Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room” she was restoring as senior contract consultant at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. “The Peacock Room” (which can also now be viewed virtually at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art website) is opulently decorated in blue-green paint and gold leaf, with opulent Anglo-Japanese murals of peacocks on the walls and window shutters.

“There are only two artists right now, Rembrandt and Whistler, who have biographers who study them with the perfect three-legged stool of conservation: science, art history and studio art techniques. Ernst van de Wetering for Rembrandt and Margaret MacDonald for Whistler,” says Stoner. Through her Ph.D. studies, she got to know MacDonald well and Stoner is proud that she uncovered several previously unrecognized elements in Whistler’s work. (And she interviewed van de Wetering for the Oral History project.)

Still, with all the study of Whistler’s art, there were some things that went with him to his grave.

“We used to laugh up in the scaffolding, saying, ‘Wouldn’t it be lovely if we could hold a séance with Whistler and ask him how glossy he wanted the varnish?’ Then, when I started working with Andrew Wyeth later, I was happy to be able to ask him directly about varnishes.” Wyeth, when Stoner asked him about his own work, said he had stopped using varnishes altogether. “He wanted the surfaces to look dusty,” she says. “Like dead flies, or a mummy. Just so dusty.”

The Artist’s Confidante

Stoner divides her main life as a conservator into three parts: 10 years of Charles Willson Peale; 10 years of James McNeill Whistler; and then 10-plus years of Andrew Wyeth. That final part is perhaps what Stoner is most known for — she became very close with the famed American artist before his death in 2009 as his primary conservator, she remains connected with his family, and has served as a board member of the Wyeth Foundation for American Art since 1999. He also painted her portrait in 1999.

Wyeth is known in American popular consciousness for his famous 1947 painting “Christina’s World,” in which a woman lies in a field and looks over at a barn and farmhouse in the distance.

Stoner first connected with the Wyeth family after attending a conference of conservators in 1980 in Ottawa, Ontario, where she heard several speak about working with living artists. She realized the Wyeth family was living in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, not far from her in Delaware. She reached out to Andrew’s son, Jamie, who is also an artist, who at the time was furious about a conservator’s wrongful varnishing of one of his paintings.

“That lit a fire in me to teach and give talks about the importance of working directly with artists,” she says.

Stoner met Andrew Wyeth in 1997. The Delaware Art Museum and the Farnsworth Art Museum were organizing an exhibition about Wyeth and his son Jamie, as well as Wyeth’s father, the painter N.C. Wyeth, and Howard Pyle, the painter who trained N.C. Wyeth. Stoner wrote a booklet about their techniques that accompanied the exhibition. (Watch a video about Stoner's work with the Wyeths from the Brandywine River Museum.)

She traveled to Maine to interview Andrew in what would be the first of many conversations over lunches and drinks with him and his wife, Betsy, who was constantly quizzing her on various art history concepts (“Why did the cavemen paint?”) or stopping her in her tracks with pronouncements such as, “Artists don’t want to hear what’s wrong with their paintings” (making the job of writing a treatment proposal quite difficult)!

Stoner also got to know Andrew’s neighbor and muse, Helga Testorf. Wyeth had a public scandal in 1986 when a series of 247 paintings had made of Helga over 14 years (some of them nude), without the knowledge of his wife or Testorf’s husband, were purchased by a collector and exhibited.

“Andrew had one personality with Betsy, but was more himself with Helga, I think,” she says.

Being able to work directly with the artist on his works changed the way she approached their restoration. For example, if a painting had a scrape on it from handling that would normally be inpainted (retouched) by a conservator, Wyeth would instead say, “‘Keep that scrape! It makes the barn look more real, like it has more age and more use,’” says Stoner.

Wyeth often worked in tempera paint, which can develop efflorescence over time — a white dust that looks almost glittery. If some had developed on a painting depicting snow, he did not want it removed. “If other conservators haven’t read my papers or asked me about it, they’ll just brush it off,” she says, with a hint of frustration.

It’s generally accepted now, she says, to follow the wishes of a living artist, but she acknowledges that there are complicating factors — what if the artist’s wishes would cause a work to deteriorate, and the owner who spent several million dollars on it doesn’t want that to happen?

In one case, when Stoner removed varnish from a Wyeth painting that had been wrongly coated by an art dealer, Wyeth’s signature was soluble in the varnish. So he stood beside her while she removed it and then he re-signed the painting — however, then the signature on it was almost 40 years newer than the painting, creating a headache for future authenticators (though Stoner carefully documented the change).

“There’s a famous story: Degas [Edgar Degas, the French impressionist] dined with one of his patrons and looked up at his painting on the wall and said, ‘There’s something I’d like to add to that.’ And the patron never saw it again! Many museums won’t allow a living artist to make corrections that could be in a 2012 style on a painting from 1982 — and certainly not to take it back to the studio!”

The Author

The Oral History Project is not the only way Stoner has documented the changes in the field of art conservation over her lifetime.

She also edited the 900-page “Conservation of Easel Paintings,” which was first published in 2012. Stoner said it was quite challenging, as conservators from different countries and schools of thought often disagreed about which techniques were best, leaving Stoner to try to include multiple perspectives.

The struggle was worth it, she says. “This wonderful Romanian man came to me at a conference and said ‘You know you have written the Bible.’ In this case, actually, I edited the Bible, and wrote a few chapters and verses.”

Her co-editor, Rebecca Rushfield, assembled the extensive bibliography. Rushfield also works with Stoner on the oral history project and has contributed to her theatre productions. She met Stoner as a student at NYU when Stoner was working on the journal Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts.

“She’s very convincing. She was telling us about how important abstracts were and ‘didn’t we all want to write abstracts for the journal?’ She’s a big concept person, whereas I’m more in the details. For the book, for the Oral History Project, she just knows everyone and persuades everyone to contribute.”

A second edition of the book was published in 2021 to include new research and technologies.

“The new techniques since 2012 are just so exciting,” Stoner says, citing scanning macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF), a nondestructive imaging technique, and computer weave mapping, which can show whether two paintings came from the same rolls of canvas, as two of many examples.

“When I was at NYU, I could put all the books I needed to read for conservation in one suitcase,” she says. “Now I can’t even put all the books published in one year in a suitcase.”

The Advocate

Aside from advances in technology, Stoner sees the diversification of the conservation industry as a positive sea change. She remembers when she began her conservation studies at NYU in 1970 and “some conservators and curators didn’t think about salaries because they were rich. They could do the work because they had inheritances. We’re still fighting that elitism in some ways.”

For example, she says, “We realize not everyone can or wants to go to Europe to study the Old Masters,” she says. “Art is incredibly diverse, and our goal is that conservators should reflect the diversity of the population they serve and the art they work on.”

For example, she says caring for Native American objects in a culturally sensitive way has changed the way conservators think about their work. Some objects are removed from collections to be ceremonially treated with smoke by tribal leaders, whereas conservators typically view smoke as a damaging substance to be avoided. Costumes might be worn for a dance and then returned to the collection needing cleaning or beads reattached. There are rules about certain objects being touched by women.

Stoner attended a conference in 1999 about conserving art collections at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), where several collection curators requested Black conservators to work on their art — and there were few available.

“The current programs are working together to try to get curators and professors at HBCUs, when they see a student who is interested in the three-legged stool of conservation, to encourage them to go into the field — just like Tom Thorne and Carl Roseberg did for me at William & Mary,” she says.

The Actor and Playwright

Though she made the decision to become a conservator, Stoner didn’t leave theatre behind — far from it. She decided to do “conservation by day and theatre by night,” and her theatre productions are some of her proudest accomplishments.

While a student at William & Mary and for many years after, Stoner often performed at the Wedgewood Dinner Theatre just outside Williamsburg, the Albemarle Playhouse in Charlottesville, and in the Common Glory, a production about the American Revolution staged each summer at the Lake Matoaka amphitheatre a few years later, award-winning actor Glenn Close ’74, D.A. ’89, H.F. ’19 would also get her start there).

While living in New York City, she collaborated with her W&M friend Bill Brooke again on the musical “I’ll Die If I Can’t Live Forever,” which The New York Times called “the best mini-musical in town” in November 1974.

Creating theatre productions about historical figures from the art world — including the three main artists in her life in art history, Peale, Whistler and the Wyeths — allowed her to mix her passions. She was also commissioned by the Delaware Humanities Council to write musicals about women's suffrage and the Underground Railroad for Delaware schools.

She is the lyricist for “Shanghai Sonatas,” about Jewish refugee musicians in Shanghai during World War II. “Shanghai Sonatas” has been workshopped several times in New York City and most recently in Los Angeles.

Just Say ‘Joyce’

Looking back on her career, Stoner says conservation is now actually a “10-legged settee” — along with the original three original elements of science, art history and studio techniques, she adds ethics, fundraising, diplomacy, museum management, legal issues, public outreach, education, diversity, health and safety, and skills in documentation using sophisticated imaging. But it’s an environment in which she thrives.

Alongside her program director and conservator duties, she’s still in the classroom, ensuring the next generation of conservators are preserving art for the next generation.

Rushfield remembers when Stoner brought a group of students to a conference in 2006 for the anniversary of the Florence flood.

“She really mentors her students, providing experiences for them, introducing them to the people she knows and keeping in touch to make sure they succeed long after they’re her students,” she says.

As to Stoner’s impact: “Joyce is one of those people in the field who is known by just her first name. You say ‘Joyce’ and everyone knows who you are talking about.”